Syndicated from https://recipes.hypotheses.org/8065

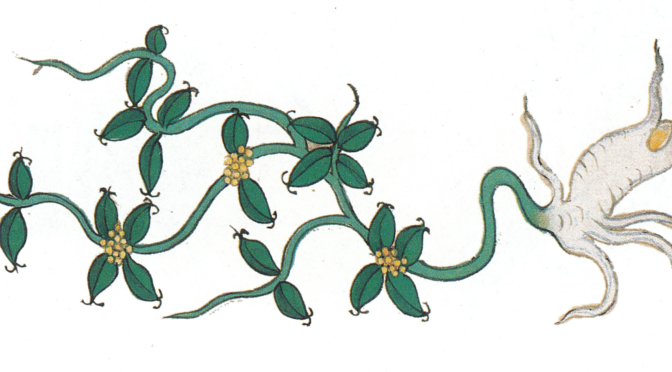

One striking feature of classical Chinese pharmacy is the abundant use of toxic substances. Prominent examples are aconite, arsenic, and bezoar. Fully aware of the toxicity, or du, of these substances, Chinese doctors developed a variety of methods to prepare and deploy them for therapy. How was such knowledge produced in medieval China? And how did it migrate from one space to another? Here I use several medical documents from the seventh century to address these questions, focusing on gouwen 鈎吻 (Gelsemium), a highly toxic herb growing in southern China (opening image).[1]

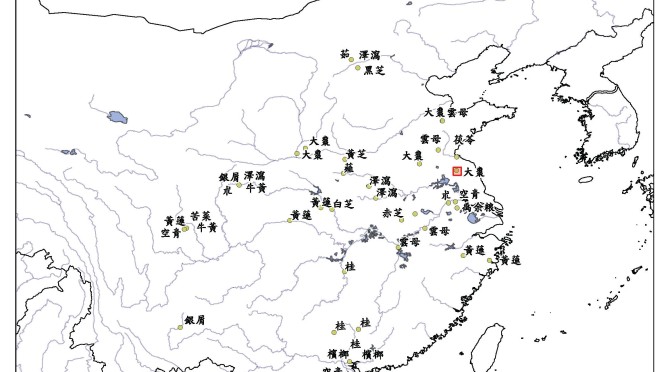

The seventh century is a crucial moment in the history of Chinese medicine. The favorable political environment of early Tang dynasty (618-755) fostered the flourishing of medical ideas and the formation of a number of influential texts. One of them is the Newly Revised Materia Medica (Xinxiu bencao 新修本草, 659), the first state-sponsored pharmacological text produced in China. Compiled by more than twenty court officials, the text reflects the government’s effort to standardize medical knowledge. Gelsemium is one of the 850 drugs in the book (Fig. 1). Defined as warming, pungent, and highly toxic, the root of the herb could cure, among others, wounds inflicted by metal weapons, ulcers, swelling, and convulsion. The authors also stressed the great danger of the herb by showing that drips squeezed from one or two leaves would suffice to kill a person. But not a goat. Quite the contrary, its sprouts could make the animal grow large. It must be, the authors mused, the case that everything in the world submits to something else.

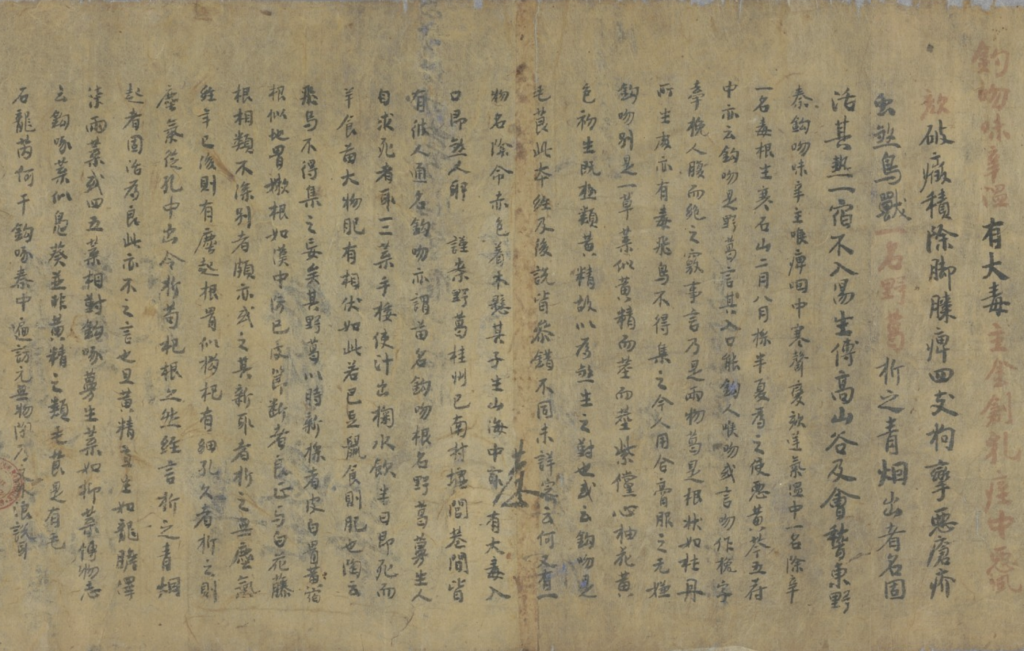

This copy of the text is from Dunhuang (P. 3714), dated to 667 or later. Image courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France (Gallica).

Gelsemium was also embraced by doctors at the time. Sun Simiao 孫思邈 (581?-682), one of the most famous doctors in Chinese history, incorporated the drug into his Essential Formulas Worth A Thousand in Gold for Emergencies (Beiji qianjin yaofang 備急千金要方, 650s). The toxic herb appears in nineteen prescriptions in the text, primarily for topical treatment. In one case, Sun presented a formula called “Ointment of Gelsemium” to treat toxic swelling, pain and numbness in the limbs, ulcers, weak feet, among other conditions. At the end, he warned: “This formula should not be given to vulgar people. Be cautious.”

Why did Sun keep the formula away from vulgar people, a term probably referring to commoners? Two possible reasons. First, handling Gelsemium was a delicate matter. Due to its high toxicity, any misuse of the herb could result in dire, if not lethal, consequences. Commoners may not possess the proper knowledge of deploying the herb, hence they should refrain from taking this formula. Second, because Gelsemium straddled medicine and poison, laymen might easily use it to harm others. By restricting its access, Sun tried to prevent such malicious misuse. Contemporary sources echoed Sun’s concern. According to an eighth-century statute of medical practice, private families were forbidden to possess Gelsemium. The government tightly controlled the access of the toxic herb to prevent it from falling into the wrong hands.

This begs the question whether the plant was actually used as a medicine. At the high level of the society, this is likely the case. The evidence came from a precious collection of medicines preserved in the Todaiji Temple in Nara, donated by the Empress Dowager Komyo in 756 as a gesture of benevolence. Because of the vibrant cultural interaction between China and Japan at the time, many drugs of Chinese origin travelled eastward. Gelsemium was one of them (Fig. 2). It is possible that the herb reached Japan as an item of exchange between the two imperial courts that appreciated its medicinal value.

Temple in Nara, dated to the eighth century. The roots are 0.5-2.0 cm in diameter and 17-24 cm in length. Image courtesy of the Imperial Household Agency website.

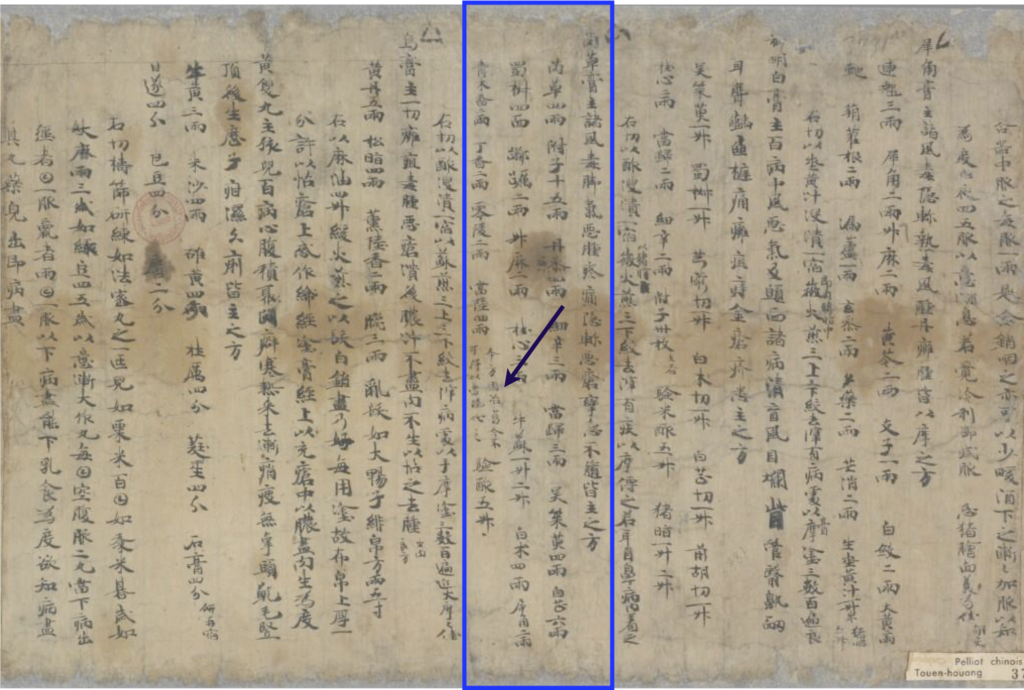

In the local community, the situation was different. We get a clue from a seventh-century manuscript from Dunhuang, a town located in the far west of the Tang Empire on the Silk Road. The manuscript contains miscellaneous formulas, many for external application. One, called “Ointment of Illicium,” merits our attention (Fig. 3). It closely resembles Sun Simiao’s formula that I showed above, but with an important variation: it doesn’t use Gelsemium. Underneath the ingredient Phytolacca (danglu 當陸), we find an explanation: “The original formula uses Gelsemium. Nowadays it cannot be obtained, so one uses Phytolacca to replace it.” We can posit why this happened, given Gelsemium’s habitat in southern China, which is far away from Dunhuang, and its restricted access to commoners, as explained earlier. By contrast, Phytolacca was a local herb whose medical function substantially overlapped with that of Gelsemium, making it a reasonable substitute for the distant, unattainable plant.

This example of drug substitution is telling. Compared to social elites, lay people in local communities faced the challenge of limited medical resources. Consequently, they sought alternative options. The rise of authoritative texts at the imperial center thus went hand in hand with its fluid transformation as it moved in various geographical and social domains. Medical knowledge, upon transmission, was destabilized, begetting varied practices in society.

Notes

[1] This illustration of gouwen (Gelsemium) is from a late sixteenth-century pharmaceutical text (Buyi leigong paozhi bianlan, 1591). Reprint from Buyi leigong paozhi bianlan, ed. Zheng Jinsheng (Shanghai: Shanghai cishu chubanshe, 2008), vol. 1, 241.

![[NBN Episode] Stefan Ecks, Eating Drugs: Psychopharmaceutical Pluralism in India](https://www.asianmedicinezone.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/0.jpg)