Is traditional Malay medicine based on superstition and folklore or grounded in scientific evidence? Nadirah Norruddin uncovers the varying perceptions of Malay medicine in colonial Malaya.

This post first appeared on BiblioAsia. It is syndicated here with permission.

Malay ubat-ubatan (medicine) and healing – which spans many centuries and has been passed down through generations either orally or in written form – is a complex and holistic practice.

Traditional Malay medicine incorporates principles and practices of pharmacology that are highly dependent on indigenous flora and fauna found in the wild.1 Age-old literature and manuscripts – although scarce in number – document the ways in which plants, animals and minerals2 native to the Malay Archipelago have been part and parcel of its healing practices. At the heart of Malay ubat-ubatanis the amalgamation of complex Islamic and Hindu beliefs and practices presided over by traditional or faith healers.

Colonial scholars and administrators in 20th-century Malaya were invariably conflicted in their perceptions of traditional Malay medicine. Local sources and interpretations were frequently overlooked, and this has in turn affected the way in which traditional Malay medicine has been studied and understood for decades. Some defined ubat-ubatan as remedies administered according to the principles of chemistry and scientific evidence, while others dismissed such healing practices as belonging to the realm of magic and the supernatural. For the most part, the British regarded traditional Malay medicine with suspicion and antithetic to its Western counterpart.

As a result, the practice and form of traditional Malay medicine underwent dramatic changes under colonial rule. Legislations, for instance – shaped by altruism or bigotry, but more likely a combination of the two – were introduced by the British to stamp out traditional Malay healing practices and regulate village healers.

The Spread of Islam and Malay Medicine

The adoption of Islam in the Malay Archipelago from the 13th century onwards not only introduced a new religious doctrine to the region, but also fostered a pan-Islamic identity and defined new parameters for the spiritual, social and economic way of life of its inhabitants. Gradually, Islam became syncretised with the prevailing belief systems of the Malay world.

Western scholars of the time held the view that the Malay community adopted a hybridised form of Islam. In his address before the Straits Philosophical Society in 1896, English orientalist and linguist Charles O. Blagden postulated that Malays were “only superficially Muhammadan” as their folk rituals were “unorthodox” and “pagan” in relation to the basic tenets of Islam.3 Such an assertion, however, simplifies the complex understanding and expressions of a dynamic and multifaceted faith.

Medicine in Islam is characterised by a history of enquiry, innovation and adaptation. This is reflected in the ease in which indigenous healers adopted and adapted Islamic symbolism in their practices. In the Malay Peninsula, ceremonies overseen by the pawang (or shaman) include Quranic incantations and prayers addressed solely to God, even though most other aspects of the rituals are Hindu-Buddhist or pre-Indic in character.

Although the origins are unclear, the Malay method of healing is mainly administered by the traditional medicine man or bomoh (see text box), who derives his knowledge from either ilmu turun (inherited knowledge) or ilmu tuntut (apprenticeship) and, in some instances, complemented by the Kitab Tibb (The Book of Medicine).

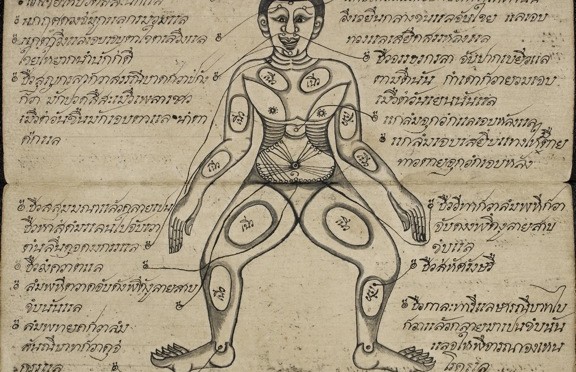

There are numerous versions of Kitab Tibb manuscripts found in the Malay Archipelago. Mostly written between 1786 and 1883, these broadly outline three main types of healing practices: those using natural resources such as plants and herbs; those relying on wafaq (written symbols or amulets); and healing practices using Quranic verses, supplications and salawat (blessings to the Prophet). All these techniques can be used simultaneously or separately.4

The earliest edition of the Kitab Tibb was written on 12 wooden sheets, and prescribed medications based on plants, herbs and spices commonly found in the region. The manuscript also includes a list of dietary restrictions and a variety of taboos (pantang larang) the afflicted should observe.5 By the 19th century, surviving copies of the Kitab Tibb in the Malay Peninsula were known to contain detailed observations by the bomoh, including visual representations of disease symptoms as well as the appropriate incantations.

Types of Healing

Traditional Malay healing offers a holistic, multifaceted and ecological solution to a multitude of illnesses and ailments. It comprises aspects of the spiritual, such as magic, shamanism and the supernatural, and the empirical, such as dietetics and herbalism, which can be scientifically explained.

Although Islam may have encouraged the use and incorporation of nature in traditional Malay medicine, natural remedies were already widely used in local healing practices and rituals prior to the arrival of Islam in the Malay world. For example, common plants, herbs and spices like bonglai (Zinggibar cassumunar) had been used to treat migraine, cough and gastrointestinal problems for centuries.

As observed by British physician John D. Gimlette in his book, Malay Poisons and Charm Cures (1915),6 bomohs used rattan splints for simple fractures and wood ash as an antiseptic dressing. When a baby was delivered by a bidan or midwife, the umbilical cord is cut with a bamboo stem and the stump dusted with wood ash or a paste made of pepper, ginger and turmeric.

Islamic medical science introduced new concepts to the pre-existing knowledge of the human body and the environment. The seeds of Islamic medicine and healing can be traced back to the Quran, the underlying philosophy of using flora and fauna in natural remedies grounded in the belief in Allah as the Creator of Nature. As such, tapping on the healing properties of the earth has been a long-standing aspect of the Islamic medical tradition. One of the verses from Surah An-nahl (16:69) of the Quran reads thus:

“Then eat from all the fruits and follow the ways of your Lord laid down [for you]. There emerges from their (bees) bellies a drink, varying in colours, in which there is healing for people. Indeed, in that there is a sign for people who give thought.”

Ancient medical texts in the Malay world did not have specific titles but were generally referred to as Kitab Tibb and primarily consisted of translations from Persian and Indian sources. Different manuscripts prescribed different courses of treatment even for the same ailments. Interestingly, the vast array of natural sources described in these manuscripts are likely still in use today in the Malay Peninsula, either as supplements or natural remedies.

The Andalusian botanist and pharmacist Ibn al-Baytar’s pharmacopeia, titled Compendium of Simple Medicaments and Foods and published in the 13th century, is still a widely consulted text in the world of Malay healing today. It lists 1,400 plants, foods and drugs, and their uses, organised alphabetically by the name of the plant or plant component.

Apart from their knowledge of humoural theory (see text box) and botany, traditional Malay healers also offered spiritual healing to cure the sick. The belief is that animate and inanimate objects, including the physical body, possess semangat (a vital force or soul). The loss of semangat can be detrimental to one’s physical and mental well-being.

A healer is purportedly able to manipulate and revive the semangat of the sick – particularly those suffering from mental and spiritual ailments. To treat patients who might have been “disturbed” by unseen forces, healers invoke supernatural entities through jampi (incantations), spells and elaborate rituals. Such ceremonies may sometimes take the form of a public event, witnessed by the entire village and accompanied by loud music. The public nature of such rituals was often derided by colonial administrators and scholars, who saw these practices as primitive and irrational or, as Gimlette puts it, “circumvent[ing] Muhammadan tenets”.7

The Cultural and Scientific Divide

There is a paucity of comprehensive written records of traditional Malay healing as much of it have not survived the ravages of time. Whatever extant Malay manuscripts – mostly inherited and passed down orally from one generation to the next (ilmu turun) or by way of apprenticeship (ilmu tuntut) – along with books and documents authored by colonial scholars, provide the only window into the ancient practices and beliefs of the Malay world.

In striving to achieve a balance of the body, mind, health and spirit, traditional Malay medicine does not differ much from Ayurvedic, Chinese and Hippocratic traditions that emphasise the same – especially with regard to humoural theory. Colonial writings, however, have tended to focus on Malay folk religion and animism, centering their writing around the use of amulets, incantations, charms and sorcery by the community.

The late 19th to early 20th centuries saw a significant output in research by colonial scholars who studied Malay belief systems and healing practices. The body of ideas and literature generated by these early observers were often biased, filled with racist sentiments or tinged with romanticism, although some scholars were of the view that the sudden rise in writings on Malay magic and medicine was simply an effort at documenting the “primitive” and vanishing aspects of the social and cultural lifestyles of the Malays.8

The use of magic and the fervent belief in religion among Malays have often been cited as stumbling blocks to the development and progress of the community. In his September 1896 report from Kuala Langat, Selangor, where he worked in the Straits Settlements civil service, English anthropologist Walter W. Skeat made the overtly racist remark that “indolent and ignorant Malays” needed to be “saved from themselves”, and attributed the “many crippled lives and early deaths” to the “evil influence of the horde of bomors”.9 In fact, Skeat believed that increasing “contact with European civilisation” by the local Malay tribes had diminished their use of charms and spells.10

Biased perceptions of traditional Malay society, such as its healing practices, could have been used by the British to justify its political domination and imperialist motives.11 There were, however, several scholars such as Thomas N. Annandale and John D. Gimlette, who acknowledged the benefits and scientific merit of traditional Malay medicine.12 Both men were heavily involved in fieldwork and were well known for their research on traditional Malay medicine. Gimlette referenced local sources, including Kelatanese manuscripts, for his book Malay Poisons and Charm Cures (1915), which today remains a classic and definitive reference guide to the practices of Malay healers. As the use of some herbs and plants could lead to fatal consequences, Gimlette’s study of the wild varieties of vegetation in the Malay Archipelago opened up a new field of study for physiologists and pharmacologists.13

An attempt to comprehend the Malay pathological framework for medicine and disease is also evident in Percy N. Gerrard’s medical dictionary, A Vocabulary of Malay Medical Terms (1905).14 As a medical professional, Gerrard’s efforts were borne out of the desire to understand his patients’ medical ssues from a scientific and cultural point of view. This enabled him to treat his patients using Malay herbal medicine whenever necessary. Gerrard drew parallels to Western medicine and, in doing so, lent credibility to Malay practices and beliefs – at least in the eyes of the colonial administrators.

Like Gimlette, Gerrard praised the Malays’ profound understanding of plants and herbs, and highlighted the medicinal value of these untapped sources and the native knowledge of local medicine. Despite his affirmations of the scientific value of herbs in Malay healing, Gerrard felt that the community’s belief in the supernatural was an impediment to British acceptance of traditional Malay medicine and healers.

It is clear that colonial observers of 20th-century Malaya have largely contexualised their understanding and knowledge of Malay medicine against Western markers. This cultural chasm was mainly due to a lack of empathy and the inability to comprehend the complexities behind the religious rituals and healing systems of indigenous groups. For the most part, Malay healing practices were regarded as superstitions and folklore that could not be explained by scientific theories. Hence over time, some traditional Malay healers co-opted the language of religion15 and, eventually, science into their practice in order to gain wider acceptance by their Western critics.

Legislating Malay Medicine

Although Western medical services were gradually introduced to the local population, most Malays continued to consult their community healers as they allegedly had “complete faith in their own particular charms and cures” and “dread[ed] hospitals, doctors and western medicines”.16 As traditional healers were also involved in non-medical matters such as state, social and cultural affairs, they occupied an esteemed position in the indigenous communities they served.17

| Healing Practices

One of the most notable Malay medical manuscripts translated into English is Ismail Munshi’s The Medical Book of Malayan Medicine. Originally written in Jawi (c. 1850), it contains over 550 remedies for maladies ranging from migraines to depression, bloatedness and leprosy.

Reference Burkill, I.H., & Ismail Munshi. (1930). The medical book of Malayan medicine. Singapore: Botanic Gardens. (Call no.: RCLOS 615.3209595 MED) |

By the turn of the 20th century, the British had become more receptive to Malay healing practices. Although dismissive of the efficacy of traditional Malay medicine, the British were aware that traditional healers formed the backbone of a long-established support system that locals could turn to in times of physical, emotional and spiritual distress.

A significant example would be the role of the bidan, or midwife, in the community. Before the colonial government set up a maternity hospital in 1888, the demands of pregnancy – ranging from prenatal care to actual delivery and postpartum care – were handled by bidans.

Although colonial medical officers acknowledged the importance of bidans, they were concerned that these midwives were operating under unsanitary conditions. In the early 20th century, a surge in the infant mortality rate was mainly attributed to traditional midwifery practices: many babies died from Tetanus neonatorum (umbilical infection).18 The authorities thought it imperative that bidans be trained and supervised to reduce maternal and infant mortality rates, and to develop trust and spread awareness of Western medical services among Malay mothers.

Under the Midwives Ordinance enacted in the Straits Settlements in 1915, all bidans had to be registered with the Central Midwives Board and undergo in-service training. Local women were also trained in biomedicine, midwifery and nursing in order to replace the traditional role of the bidan. The intention was not to encourage women to deliver in hospitals (due to a lack of beds and facilities), but rather to establish a pool of trained and licensed midwives who could recognise complications during pregnancy and refer the women to the hospitals if necessary. By the 1920s, mobile dispensaries as well as home and school visits were available to communities living in rural areas, and public campaigns were mounted to ensure that people had access to medicine and healthcare.

By 1936, there were 720 trained midwives in Singapore, 574 in Penang and 224 in Malacca. Despite these efforts, traditional bidans were still sought after by Malayan women in the subsequent decades due to the personal nature of the antenatal and postnatal services they provided, including up to six weeks after delivery.

Two other legislations introduced by the colonial government further threatened the existence of traditional healers and the provision of traditional medicine. Under the Sale of Food and Drugs Ordinance that came into force in 1914, the sale of adulterated drugs was deemed an offence “if the purchaser [was] not fully informed of the nature of adulteration at time of purchase”.19 The second legislation, the Poisons Ordinance of 1938 “regulate[d] the possession and sales of potent medicinal substances, to prevent misuse or illicit diversion of poisons”.20

These laws compromised the role of traditional Malay healers in the community, especially given the latent suspicions surrounding Malay medicine. However, due to the high costs involved in establishing an islandwide public healthcare system, the British authorities were rather lax at enforcing these legislations, and allowed itinerant and home-based traditional healers to continue practising their craft.

With the introduction of Western-style healthcare, including clinics and hospitals, and the increasing availability of over-the-counter medications from the turn of the 20th century onwards, traditional Malay healing played a smaller role in the lives and rhythms of the community.

State controls and the exposure to Western education further put paid to the services of traditional Malay healers. Although their numbers have drastically dwindled over the years, traditional Malay medicine continues to play an ancillary – and occasionally complementary – role to Western medicine today for those who recognise its efficacy in providing ritual care and treating spiritual ailments and conditions not yet acknowledged in Western medical science.

| Humoural Theory and Malay Medicine Humoural theory, which is one of the oldest theories of medicine, is organised around the four humours – blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile – and is associated with the four elements of earth (flesh), water (phlegm), air/wind (temperament), and fire (blood). The four elements are in turn paired up with the four qualities of cold, hot, moist and dry. Each individual has a particular humoural makeup, or “constitution”. As optimal health is attained when the humours are in harmonious balance, any imbalance of the humours may result in disease and sickness.In one of the earliest Malayan accounts of humoural theory, English scholar Thomas J. Newbold describes Malay medicine as being based on the fundamental “principle of ’preserving the balance of power’ within the four elements, specifically, air, fire, water and earth”.21 This ranges from the consumption of certain hot or cold foods (such as meat and fruit respectively), hot and cold temperatures, wind, micro-organisms and supernatural forces. Dry chills and dizzy spells arise when the “earth” element is too strong and from ailments such as cholera and dysentery, which are caused by excessive heat and moisture from the “air”.22 Consuming large amounts of food that contain “air” may cause feebleness in some. The plants and herbs prescribed by Malay healers help to revitalise and restore these imbalances in the human body. |

| Pawang, Bomoh And BidanTraditional Malay healers are the main providers of Malay medicine. To achieve the necessary credentials, some have resorted to living in solitude, spending their time meditating, fasting or putting themselves through strict dietary regimens – all in the name of spiritual cleansing. Healers are also expected to have an extensive knowledge of botany and nature so that they can classify and identify the right plants and herbs as well as their healing properties, and prescribe the correct remedies.

Pawang A pawang is commonly defined as a shaman or general practitioner of magic who incorporates incantations into his craft. He is usually involved in conducting agricultural rituals and divination ceremonies to sanctify the village. Pawangs have also been referred to as “wizards” by scholars such as Richard J. Wilkinson for their ability to manipulate the course of nature through the use of incantations and divination practices. Dukun/Bomoh A dukun or bomoh is a general practitioner who treats fevers, headaches, broken bones, spirit possession and various ailments. The skills and reputation of a dukun/bomoh stem from the person’s knowledge of humoural medicine, the healing properties of local flora and fauna as well as syncretic ritual incantations. Some were well known for their treatment of victims of sorcery. The bomoh akar kayu (the latter words meaning “roots” in Malay) is known for his expertise in gathering and preparing ubat-ubatan from plants and herbs In his book, A Descriptive Dictionary of British Malaya (1894), Nicholas B. Dennys compares the dukun to “being on par with witch doctors of history”. Although the dukun has been generally described in disparaging terms by Western scholars, a small minority saw the merits of these traditional healers. Percy N. Gerrard defines the “doctor” as a bomoh, dukun or pawang in his dictionary, A Vocabulary of Malay Medical Terms (1905). Bidan Also known as “Mak Bidan” or “dukun beranak”, these midwives specialise in women’s health matters, including fecundity, midwifery and contraception, along with a variety of beauty-related disorders. Up till the 1950s, it was common for mothers in Singapore to deliver their babies at home with the help of village midwives. Today, the role of these women is limited to providing antenatal and postnatal care, such as confinement services for new mothers or general massage therapies. References Dennys, N.B. (1894). A descriptive dictionary of British Malaya (p. 104). London: London and China Telegraph. [Microfilm nos.: NL7464, NL25454]. Gerrard, P.N. (1905). A vocabulary of Malay medical terms (p. 24). Singapore: Kelly & Walsh. (Microfilm no.: NL27512) Skeat, W.W. (1900). Malay magic: Being an introduction to the folklore and popular religion of the Malay Peninsula (pp. 424–425). London: Macmillan and Co., Limited. (Call no.: RCLOS 398.4 SKE-[GH]) Wilkinson, R.J. (1908–10). Papers on Malay subjects. [First series, 4], Life and customs (p. 1). Kuala Lumpur: Printed at the F.M.S. Govt. Press. (Microfilm no.: NL263). |

References

Bala, A. (Ed.) (2013). Asia, Europe, and the emergence of modern science: Knowledge crossing boundaries. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSEA 509.5 ASI)

Haliza Mohd Riji. (2000). Prinsip dan amalan dalam perubatan Melayu. Kuala Lumpur: Penerbit Universiti Malaya. (Call no.: Malay RSEA 615.88209595 HAL)

Harun Mat Piah. (2006). Kitab tib: Ilmu perubatan Melayu. Kuala Lumpur: Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia: Kementerian Kebudayaan, Kesenian, dan Warisan Malaysia. (Call no.: Malay R 615.880899928 HAR)

Manderson, L. (1996). Sickness and the state: Health and illness in colonial Malaya, 1870–1940. New York: Cambridge University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 362.1095951 MAN)

Matheson, V., & Hooker, M. (1988). Jawi literature in Patani: The maintenance of an Islamic tradition. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 61(1)(254), 1–86. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

McHugh, J.N. (1955). Hantu hantu: An account of ghost belief in modern Malaya. Singapore: Donald Moore. (Call no.: RCLOS 398.47 MAC-[RFL])

Mohd. Affendi Mohd.Shafri & Intan Azura Shahdan. (Eds.). (2017). Malay medical manuscripts: Heritage from the garden of healing. Kajang, Selangor, Malaysia: Akademi Jawi Malaysia. (Call no.: RSEA 610.95 INT)

Muhamad Zakaria & Mustafa Ali Mohd. (1992). Tumbuhan dan perubatan tradisional. Kuala Lumpur: Fajar Bakti. (Call no.: Malay RSING 615.88209595 MUH)

Ong, H.T. (Ed.). (2011). To heal the sick: The story of healthcare and doctors in Penang. Georgetown: Penang Medical Practitioners’ Society. (Call no.: RSEA 362.1095951 TO)

Owen, N. G. (Eds.). (1987). Death and disease in Southeast Asia : explorations in social, medical and demographic history. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: 301.3220959 DEA)

Mohd. Taib Osman. (1989). Malay folk beliefs: An integration of disparate elements. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia. (Call no.: RSEA 398.4109595 MOH)

Tuminah Sapawi. (1997, January 8). Bidan kampung now offers massage and other rituals. The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Wilkinson, R.J. (1908–10). Papers on Malay subjects. [First series, 4], Life and customs (p. 1). Kuala Lumpur: Printed at the F.M.S. Govt. Press. [Microfilm no.: NL 263].

Notes

- The World Health Organization defines traditional medicine (also known as folk, indigenous or alternative medicine) as “the sum total of the knowledge, skill, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness”. Herbal medicines include “herbs, herbal materials, herbal preparations and finished herbal products that contain as active ingredients parts of plant, or other plant materials or combinations”. See World Health Organization. (2018). Traditional, complementary and integrative medicine. Retrieved from World Health Organization website.

- The Kitab Permata from 19th-century Patani (southern Thailand) discusses the characteristics and medicinal properties of gemstones, minerals and metals. The text is commonly used by traditional healers in the north coast of the Malay Peninsula.

- Blagden, C.O. (1896, July). Notes on the folk-lore and popular religion of the Malays. Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 29, 1. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

- Malay healers used Quranic verses to supplement the efficacy of herbs and medicinal plants. Supplications remain at the heart of Malay healing. A healer may choose to use only plants and herbs with supplications but without wafaq, while another may use fewer plants and herbs and more wafaq in his practice.

- A prominent Patani scholar, Sheikh Ahmad al-Fathani, laboured his discourse in Islamic knowledge with the science of medicine. His manuscript, Tayyib al-Ihsan fi Tibb al-Insan, which was produced in 1895, was widely consulted by traditional healers in 20th-century Malaya.

- John D. Gimlette was a physician who resided in the Malay state of Kelantan for many years and was extremely interested in the subject of Malay poisons, sorcery and cures. See Gimlette, J.D. (1915). Malay poisons and charm cures. London: J. & A. Churchill. (Call no.: RRARE 398.4 GIM-[JSB])

- Gimlette, 1915, p. 106.

- Winzeler, R.L. (1983). The study of Malay magic. Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde, 139 (4), 435–458, p. 436. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

- Malay “doctors”. (1896, September 22). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- Skeat, W.W. (1900). Malay magic: Being an introduction to the folklore and popular religion of the Malay Peninsula (pp. 424–425). London: Macmillan and Co., Limited. (Call no.: RCLOS 398.4 SKE-[GH])

- Winzeler, 1983, p. 447.

- Thomas N. Annandale was a Scottish zoologist, entomologist, anthropologist and herpetologist, who became interested in Malay animism, related magical lore and curers.

- From pineapples (Ananassa sativa) and keladi (Alocasia denudata) to cheraka (Plumbaginasea), the poisons Gimlette examined have been described to contain active ingredients useful in the study of modern medicine.

- Gerrard, P.N. (1905). A vocabulary of Malay medical terms. Singapore: Kelly & Walsh. (Microfilm no.: NL27512)

- Anthropologist Thomas Fraser notes that in village processions led by the pawang who is healing a physically ill or possessed patient, the imam(Islamic worship leader) is also involved to officiate the ritual from a religious perspective. This prevents any possible conflict with Islamic beliefs that may border on shirk (idolatory or Polytheism).

- Why fewer babies are now dying in Singapore. (1935, July 21). The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

- In the Malay villages, traditional healers were involved in sanctifying the village via ceremonies and rituals, and were also involved in the affairs of the state. Known as the Maharaja Lela in Selangor or Sultan Muda in Perak, a bomoh enjoyed unfettered entry into the palace compounds.

- Owen, N.G. (Ed.). (1987). Death and disease in Southeast Asia: Explorations in social, medical and demographic history (p. 258). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 301.3220959 DEA)

- Singapore. The Statutes of the Republic of Singapore. (1987, March 30). Sale of Drugs Act (Cap 282, 1985 Rev. ed.). Retrieved from Singapore Statutes Online website.

- Singapore. The Statutes of the Republic of Singapore. (1999, December 30). Poisons Act (Cap 234, 1999 Rev. ed.). Retrieved from Singapore Statutes Online website.

- Newbold, T.J. (2015). Political and statistical account of the British settlements in the Straits of Malacca, viz. Pinang, Malacca, and Singapore, with a history of the Malayan states on the peninsula of Malacca vol, 2 of 2 (p. 242). London: Forgotten Books. (Call no.: RSING 959.5 NEW)

- Squeamishness, heartburn and fevers arise when the “fire” element is too strong. The “water” element causes damp chills and vomiting.