This is a syndicated post that first appeared at www.cpianalysis.org.

When we do textual research on China, we rely on canons that were made with paper. The gold standard for a digital corpus is that it is paired with images of a citeable physical text produced in known historical conditions: at a specific time and place, by a known author or community, or as close to that as possible. Even more, the basic organisation of our wonderful modern databases is structured according to the catalogue and chapter headings of the original collections, which are essentially finding tools for paper archives. While these categories organised the literature and made it easier to find, they also profoundly influence how we, in turn, organise our own research, and how we write history.

The problem is that the categories of researchers change with time. As we analyse our sources in new ways, we give priority to certain texts or features over others, effectively re-indexing them to suit our purposes. Usually, textual scholars will privilege a few texts as case-studies for close study, because we lack the tools for large-scale analysis of textual corpuses to make summative statements about a field of knowledge, or to track changing patterns of a field over time. We can perform thorough and extensive searches for single or a few terms across wide sets of literature, but the long lists of results that are returned are unreadable by humans.

Figure 1: Search result for a single term, gancao 甘草 (liquorice) in a major text collection

We have a problem of too much information, and too few ways of making sense of it.

In my digital work in the combined histories of Chinese medicine and of Chinese religions, I wish to make a critical intersection into how we theoretically interpret, and digitally analyse our sources. The history of Chinese religions has recently taken on some new directions in the theory of practice. In order to better understand the ways in which historical actors creatively combine aspects of “different” religions, such as Buddhism and Daoism, some scholars have started modelling religions as “repertoires of practice.” This has a very productive overlap with actor-network theory in Science and Technology Studies (STS), which also sees knowledge as produced by “clots” or “assemblages” of people and things, practices, thoughts and institutions and many more. Furthermore, the concept of “situated knowing” that came out of STS argues that different actors organise knowledge differently; there is no single, authoritative perspective on a particular field of knowledge.

This theoretical conjunction raises an important methodological question: How can we identify, sort through and organise a history of “repertoires of practice,” as they are enacted by historical actors of different stripes? Especially when these practices are disparate and escape the cataloguer’s eye? How can we tell when and which practices are being combined and deployed, in concert or separately, and whether concentrations of practices remain constant across different sectarian affiliations, or whether they change in significant ways? Can we identify patterns of change or stability?

In the Drugs Across Asia project, Chen Shih-pei and I are developing a pilot platform to test how to do exactly this. With generous support from Department III of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (MPIWG), in collaboration with the Research Center for Digital Humanities at National Taiwan University (NTU), and with Dharma Drum Institute of Liberal Arts (DILA), we are undertaking a pilot study to analyse all Daoist and Buddhist Canon and most medical sources up through the Six Dynasties (to 589 CE) for the presence of drug terms.

In stage one, I use a statistical tool developed by NTU to analyse the texts to identify where drug knowledge is located among the set of sources. NTU have uploaded all the texts for analysis as separate juan in the form of *.txt files. I have selected a combination of open source texts from various sources, primarily drawing from Kanripo. I then upload a large list of known drug terms (11,000!), which the tool uses to analyse which drugs appear in which juanaccording to frequency, and produces a list like this one.

Figure 2: Chapters from Buddhist and Daoist Canons, according to Drug Term Frequency

From this list, I select the juan for further analysis. It is somewhat self-selecting, as I sort according to how many terms appear per juan. After this, I analyse whether or not the found terms are homonyms for other things, such as relics, deities, or other terms. In this method, more hits is a good thing, because a high concentration of terms per juan is an indicator that drugs are an important topic in that text.

Figure 3: Drug terms in Buddhist monastic codes

From this data set, I can already begin to compare drug repertoires of different communities. For example, the graph above shows clusters of drug terms from five different Buddhist monastic codes. The terms that appear between the clusters are shared between two or more texts. When compared to an early Chinese materia medica, as in the graph below, it is visibly clear how different the drug lore from China and from India was. There are only a very few common terms between the Chinese text and the five Indian texts. These terms need to be more thoroughly analysed to explain these differences and correlations, but the foundations of a research paper are already here.

Figure 4: Buddhist Codes compared to Chinese Materia Medica

In the second stage, we mark up individual juan. It is exciting how easy MARKUS makes it to do this work. Using Keyword Search, I can paste my entire list of drug terms into MARKUS, and with one click identify which of those 11,000 terms appears in the text and where. This lets me quickly and easily see where the “action” is, where the drug knowledge is concentrated, without having to read through the entire juan first. I can then go and review how drug knowledge is framed and organised in that text in particular.

This way of organising reveals the “ontology” of the drug knowledge in the juan. Does it mention other important data like disease terms, drug properties, anatomical terms, or material practices like decocting, chopping, or roasting? Geographic terms? Famous people or locations? These are all important for how drug knowledge is figured. I scan through the text to pick out a representative section, and use Manual markup to highlight these salient features. Having been captured by MARKUS, they can be produced as a data table. Through this process of reading and marking up terms, MARKUS enables the ontology of each text to emerge as a data structure directly from the organisation of the text itself.

Figure 5: Ontology marked up in MARKUS

I then work closely with DILA to mark up the texts. DILA are responsible for producing CBETA, one of the foremost digital humanities projects in East Asia, and thus have extensive experience with marking Buddhist texts. I forward them the file, and they clean up the automatic marking, and use the sample ontology I’ve provided to continue to manually identify corresponding features throughout the rest of the text. I check over the results, and forward the marked file to NTU to upload into the analysis platform.

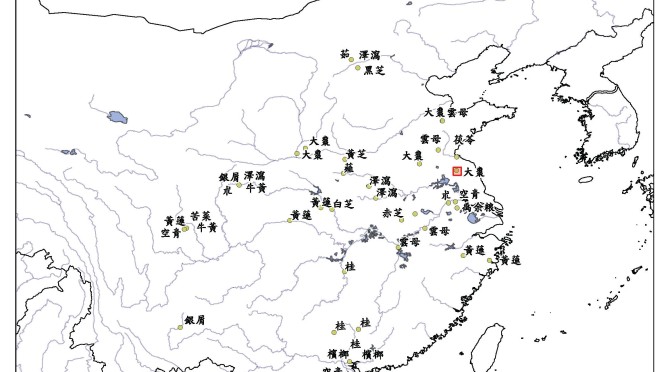

NTU are currently developing a platform called DocuSky , based on the engine behind the Taiwan History Digital Library. This platform will enable detailed analysis of the resulting markups. It will incorporate detailed meta-data for each text – telling when and by whom a text was compiled or written, in what literary genre, with what sectarian identity, and if available, in which geographic location. By analysing this detailed meta-data along with the markups, I will be able to analyse through which communities what drug knowledge travelled, and, given enough meta-data, at which times and places. The platform will also be capable of visualising the data on a GIS map and dynamic timeline, as in the existing MPIWG platform, PLATIN.

Figure 6: PLATIN Place and Time Navigator

With this tool, I should be able to quickly identify identical and similar drug recipes at scale, as well as when, where and with whom they travelled, and how they were interpreted. This will provide a much broader and more complex picture of who knew what about which drugs than can currently be known from studying materia medica (bencao 本草) literature. I should be able to track changes in properties of drugs and recipes as they circulated through historical communities, and to do so at scale. It is a mainstay of medical history to compare different community interpretations of a single drug or recipe, but no one has compared large-scale patterns of change and transfer before. By identifying which communities possessed and transmitted which drug knowledge, this platform will facilitate a large-scale picture of one important feature of the relationship between medicine and religion in the Six Dynasties.

While this model is custom-tailored to do research on drugs, it is highly adaptable. In the future, researchers should be able to change their categories and term sets to search for any “repertoire” or “assemblage” of terms. This could include medical data such as anatomical locations or disease names. But it could also be used to capture divinatory arts, health cultivation exercises, pantheons of gods, philosophical terms – anything you can develop a good term list for. I hope this set of tools will enable the fields of religious studies and medical history to come to much more nuanced descriptions of the histories of material (and immaterial) practice.

HH2031 History of Food in China Syllabus

HH2031 History of Food in China Syllabus