YiMovi: traditional Euro-American medical humanities approaches to teaching with Chinese film

YiMovi applies traditional Euro-American medical humanities approaches to teaching with Chinese film.

Medical humanities (MH) was initially concerned with the training of medical practitioners in hospitals and medical schools. Major themes are understanding the patient experience, establishing empathy, medical ethics, the history of concepts of disease and therapies, and medicine and the arts. It is inherently interdisciplinary and commonly uses literature, theatre and the visual arts in participatory ways. In recent years the term Health Humanities has been used to embrace all the ways in which healthcare involves those other than professional medical communities.

YiMovi has emerged through our teaching MH to Chinese students. This has brought up critical points of cultural difference, and has highlighted the unique challenges that the Chinese speaking worlds face. It also brings a critical focus to what have been considered universal rights in healthcare, in death and dying, and medical ethics in general.

The study of medicine in China through film can also offer new insights for the Medical and Health Humanities, through a more intimate engagement with alternative health systems, but also radically different conceptions of state, community and individual. How the body has been used as a site of personal cultivation, social conformity or political contestation is all made visible in film.

Short history of the Chinese term for ‘nerve’

The following is a syndicated post from the blog “Aowen Chinese Medicine 奧文中醫: Chinese medicine in words and pictures,” by Nicolaas Herman Oving (practitioner, translator, and educator in the field of Chinese Medicine). It originally appeared at http://ovingchinesemedicine.com/uncategorized/short-history-on-the-chinese-term-for-nerve/.

I originally wrote this in response to a colleague who suggested that the Chinese term for ‘nerve’, 神經 [shénjīng], implied that the Chinese conceived of this concept as meaning: ‘links of transmission (經) of spirit (神)’. Over the years I have shared it with students and in some discussion groups as well. The feedback I received has encouraged me to correct, expand, and polish it. I also added some illustrations in this new version. I hope you will enjoy it.

I am greatly and gratefully indebted to Hugh Shapiro for his thorough research on this topic.

Introduction

Can we say that the nerves are ‘the links for the transmission of spirit within us’? Is that the way the Chinese saw it when they began to use the term 神經 [shénjīng] for ‘nerve’? When I heard that I had serious doubts, mostly because the Chinese already had an elaborate system of transportation in the body, consisting of channels, vessels, and a network of smaller conduits. I simply could not imagine that when descriptions of the nerve and the nervous system reached China, they thought: “Ah, that’s what was missing, that could be the vehicle for spirit transmission!”

I was prepared to give it the benefit of the doubt, though, and decided to see if there was any evidence for it. The combination of the two characters 神 and 經 by itself (be it very interesting) is not enough for me to believe that it became part of Chinese medical philosophy in the way that my colleague had put it.

I specialize in the Chinese-English terminology of Chinese medicine, a medicine that I have practised as well. Besides my studies in Chinese languages and cultures I have done studies in lexicology and terminology. A brief introduction to what terminology is and how it works in our field of knowledge can be found here.

Of importance for the following is: A term is only a term when it has a definition. A definition describes the concept that is conveyed by the term. When a term is translated into another language, the definition does not change. This principle is a prerequisite for adequate translation and communication in any specific subject field. There is nothing special about it; it is the way knowledge is communicated in this world. Nevertheless, it often is overlooked in one particular field of knowledge, namely Chinese medicine.

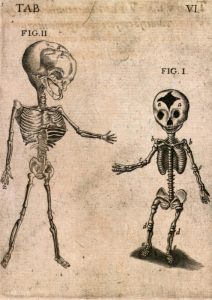

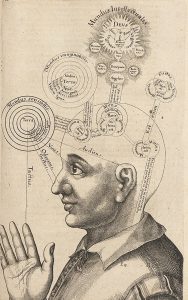

<Anatomiae amphitheatrvm, Robert Fludd, 1623>

So, it is the definition of ‘nerve’ that applies to 神經 and vice versa. There are many ways new terms are formed and for the Chinese terminologies of Chinese medicine and that of biomedicine (a.k.a. Western medicine) there are some specific problems. When the Chinese create new terms for concepts that they did not invent themselves, like ‘nerve’, what they are doing is trying to understand what the foreign term means (by investigating the definition of the concept) and then come up with a term for it in their own language.

If you translate that new word back into the foreign language without taking into account what definition is attached to it, you can come up with something different. And that is what happens when you translate 神經 as ‘spirit transmission’ or ‘lines for the transmission of spirit’, or ‘spirit channel’. Regardless of the problem that both characters have multiple meanings (an ignoramus could say that 神經 means ‘divine menstruation’), what you are doing when you follow this method, is giving a new and different definition to an existing term. And that makes communication in any discipline very difficult if not impossible.

The compound word 神經 [shénjīng] in the meaning ‘nerve’ is interesting because as a term it raises several questions. Imagine a doctor in China who comes into contact with Western anatomy for the first time in history. What would you say they will think? They see drawings of human bodies with lines, read the description of this new concept, and why o why don’t they come up with something like 腦經 ‘brain channel’, 腦氣經 ‘brain qì channel’ or another combination that fits what they read and see?

<De humani corporis fabrica, Andreas Vesalius, 1543, Basel>

As an aside:

The word 腦 [nǎo] in Chinese has the same definition as ‘brain’ – like many other anatomical words that were invented in different cultures without intercultural exchange. Think of ‘blood’, ‘heart’, ‘little toe’, ‘nose’, etcetera – all very straightforward terms, because they mean the same for everyone in all cultures and times.

Such questions occupied my brain when I was thinking about what my colleague brought forward, and they motivated me to search for references. And guess what? I found (at least part of) an answer to this intriguing issue that could make it even more intriguing. I have tried to summarize the story.

The history

The concept ‘nerve’ was first translated into Chinese by Johann Schreck (1576-1630), a member of the Society of Jesus who, before he sailed to China as a Jesuit missionary, had an impressive reputation in European courts as a gifted healer. Working with a Chinese scribe, he prepared a translation into Chinese of a Latin text in two parts, namely on anatomy & physiology and on perception, sensation, & movement (by Caspar Bauhin, first published in 1597 in Basel).

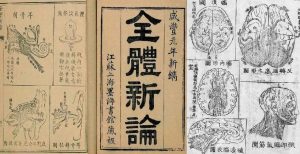

<Theatrum Anatomicum, C. Bauhin, 1605, Frankfurt>

After Schreck had served the Chinese rulers with his knowledge of astronomy (medicine and medical translation were private occupations) for a while he died, and Adam Schall (1592-1666), who had traveled on the same boat as Schreck, found a Chinese scholar, Bi Gongchen, whom Schall asked to translate the text into (more polished) literary Chinese. It was published in a single volume together with a text by Matteo Ricci, one year before the collapse of the Ming dynasty (1644).

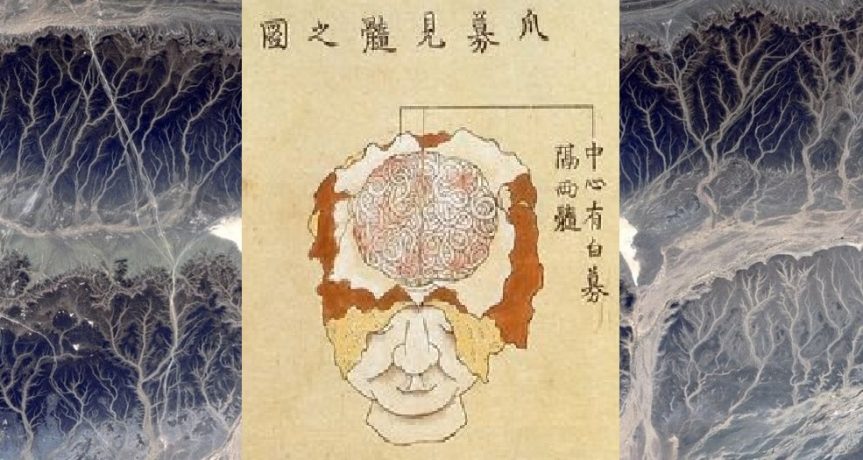

In the text, entitled ‘Western Views of the Human Body, an Abbreviated Treatise’ (Taixi renshen shuogai ), ‘nerve’ is translated as 細筋 [xìjīn], which literally translates as ‘fine sinew’. The choice for 筋 ‘sinew’ reflects the understanding of nerves in Europe at that time. ‘Nerve’ and ‘sinew’ were, for instance, used interchangeably in early 17th century texts on anatomy. Also, the Latin ‘nervus’ means ‘bow-string, tendon, sinew’.

<Taixi renshen shuogai>

In Schreck’s text nervous function is explained by using the concept of 氣 qi circulation. The ‘fine sinews’ contain qi and no blood, and when they are cut, people lose their ability to move, etc.. The book did not give the Chinese much reason to become interested in an alternate method of healing, and the concept of nerves did not take hold in China until much later.

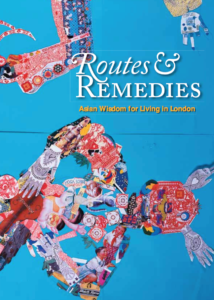

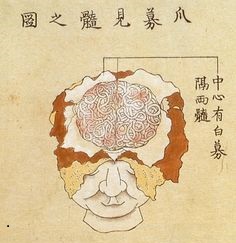

In Wang Qingren’s Yilin gaicuo (‘Corrections of Errors in the Forest of Medicine’), which after publication in 1830 became one of the most widely read medical texts in China (as it still is today), we find no mention of a term for ‘nerve’. Dr. Wang, however, recorded several anatomical notions that were revolutionary for Chinese medicine and in several ways heralded a period of modernization. For our story it is relevant that he presented anatomical ‘proof’ for what Li Shizhen had claimed in the Bencao gangmu, namely that the brain, and not the heart, was the mansion of the original spirit.

<Yilin gaicuo, Wang Qingren>

It was Benjamin Hobson (1816-1873), a medical missionary from England, who instigated renewed attention for the concept of nerve in China. With his text ‘A New Theory of the Body’ (Quanti xinlun, published in 1851) he had considerably more influence than Schreck. In the chapter on the brain and the nervous system, he introduced the term 腦氣筋 [nǎoqìjīn], which literally translates as ‘brain – qi – sinew’, that is, the sinew through which brain qi travels.

<Quanti xinlun>

Although China was in the middle of a modernization movement, in the beginning of the 20th century, the concept of the nerve was still not easy for the Chinese to digest. Of the twelve different words that had been invented for ‘nerve’ since the beginning of the 17th century, five made it to the shortlist of a terminology committee meeting held in Shanghai in 1916. The purpose of that meeting was to standardize Chinese terms for numerous scientific concepts coming from the West and biomedicine was the most important subject. The term for ‘nerve’ was debated for over two hours before 腦經 ‘brain channel’ or ‘brain tract’ topped 神經 ‘spirit channel’ by eight votes to seven.

Why did it take 300 years for the concept of nerves to take hold in China?

1. It was not particularly relevant for Chinese medicine.

2. It was associated with the Western notion of ‘volition’. The Greek term for ‘motor nerves’ was, translated literally, ‘capable of choosing, purposive’. The action of nerves was inseparable from exercise of will. In the West, volitional action was a crucial defining feature of identity. For the Chinese, who did not hold such a view of identity, the idea of incorporating nerves into medical theory was not attractive.

<Theatrum Anatomicum>

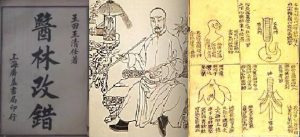

The term 神經 came to China via a different route. It was introduced in 1902 as a translation of the Japanese shinkei, which is written with the same characters. In 1774 it was coined by a Japanese doctor trained in Chinese medicine. He came up with the word after studying a post-Vesalian Dutch text on anatomy.

The story of the Japanese doctor resembles that of Wang Qingren. He went to an execution ground to observe the dissection of a cadaver in order to see whether the illustrations in the Dutch text made sense. When he was convinced that they did, he formed a translation group to study and translate the text, and that text is seen as the seed of biomedicine in Japan. He judged that the Dutch term zenuw (nerve) corresponded with keimyako – 經脈 [jīngmài], channels and vessels, and the term zenuw-vogt (nervous fluid), he argued, pointed to shinki – 神氣 [shénqì].

神氣 in Chinese medicine can mean several things: 1. spirit, vigor 2. In the Neijing, ‘spirit qì’ refers to the spirit, channel qì, right qì, the blood, and the yáng qì of the bowels and viscera. < Practical Dictionary of Chinese Medicine>. It is interesting to note that the Dutch word ‘zenuw’ (nerve) is directly related to the English word ‘sinew’.

Combining 神氣 and 經脈, our Japanese doctor-translator formed the neologism shinkei 神經 which consists of the first part of these two terms. Historians have not found evidence that the Chinese of the early 20th century were aware of the history of the term (namely that qì was part of its original full version), and argue that that is one of the reasons they favoured 腦經 [nǎojīng] as translation of ‘nerve’ in 1916.

Another note is that the word 神經 [shénjīng] already existed in classical Chinese as a designation for a genre of esoteric books. The Japanese shinkei 神經 is a new construction, derived from words unrelated to that classical meaning.

In the text mentioned below Hugh Shapiro asks the important question: Why then, did they eventually adopt the term 神經 [shénjīng] for ‘nerve’? According to Shapiro the reason can be found in the fact that thousands of Chinese trained in Japan and came back to China with Japan’s analysis of biomedicine in their luggage – accompanied by the terminology the Japanese used. Biomedicine (a.k.a. Western medicine) rapidly gained ground as part of the movement in China to modernize and catch up with the West. But more importantly, the Chinese were interested in the pathology of the nerves – a thing that was never described by the Jesuits who introduced the anatomy. And the Japanese doctors instructed the Chinese in nerve pathology as they had translated it from biomedicine.

<brain dissection, Japan, 18th century>

The concept of nerves as such did not appeal to the Chinese medical professionals (they didn’t really need it) but when they studied the illness neurasthenia as described by the biomedical literature of that time, they connected it to their understanding of depletion. In fact, neurasthenia, in Japanese shinkei shuijaku and Chinese 神經衰弱 [shénjīng shuāiruò], became much more important in China than in the countries where the idea originated but soon was discarded. Also, the foreign idea of ‘nervousness’ became very common in 20th century China.

Shapiro further argues that this can inform us that the Chinese and Western concepts of emotional and corporeal depletion were rather close, and that this is often overlooked when the differences between the two medical systems are discussed.

I might add that the ideas about several pathologies as described by Wang Qingren in connection to his, for China, rather new and revolutionary ideas about the brain and other anatomical parts, have contributed to the development of a more open view in Chinese medicine towards ‘facts’ instead of rigidly adhering to ‘theories’ only.

<Utriusque Cosmi …, Robert Fludd, early 17th century>

Literature

– Hugh Shapiro’s contribution in: ‘Medicine Across Cultures: History and Practice of Medicine in Non-Western Cultures’, a collection of essays edited by Helaine Selin (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003)

– Bridie Andrews’ Introduction in Yi Lin Gai Cuo – Correcting the Errors in the Forest of Medicine, and the chapter ‘On Brain Marrow’ in that book (published by Blue Poppy Press, 2007)

see also:

– Marta Hanson’s keynote lecture: Jesuits and Medicine in the Kangxi Court (1662-1722).

Pain, poison, and surgery in fouteenth-century China

This is a syndicated post that first appeared at http://recipes.hypotheses.org/9936

By Yi-Li Wu

It’s hard to set a compound fracture when the patient is in so much pain that he won’t let you touch him. For such situations, the Chinese doctor Wei Yilin (1277-1347) recommended giving the patient a dose of “numbing medicine” (ma yao). This would make him “fall into a stupor,” after which the doctor could carry out the needed surgical procedures: “using a knife to cut open [flesh], or using scissors to cut away the sharp ends of bone.” Numbing medicine was also useful when extracting arrowheads from bones, Wei said, enabling the practitioner to “use iron tongs to pull it out, or use an auger to bore open [the bone] and thus extract it.” More generally, Wei recommended using numbing medicines for all fractures and dislocation, for it would allow the doctor to manipulate the patient’s body at will.

Wei’s preferred numbing medicine was “Wild Aconite Powder” (cao wu san), and he detailed the recipe in his influential compendium, Efficacious Formulas of a Hereditary Medical Family (Shiyi dexiao fang), completed in 1337 and printed by the Imperial Medical Academy of the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368). In his preface, Wei affirmed that medical formulas were the foundation of medicine and that a doctor’s ability to cure depended on his ability to use these tools skillfully. Wei’s family had practiced medicine for five generations, and he synthesized their knowledge with that of other doctors to produce a comprehensive treatise encompassing internal medicine; the diseases of women and children; eye diseases; illnesses of the mouth, teeth, and throat; ulcers and swellings; and diseases caused by invasions of “wind” (ailments with sudden onset, including febrile epidemics and paralytic strokes). Numbing medicine appeared in Wei’s chapters on bone setting and weapon wounds.

Wei’s Wild Aconite Powder is the earliest datable recipe that I have found for surgical anesthesia in a Chinese text, and it is a valuable window onto practices that were largely transmitted orally, whether in medical families or from master to disciple. Dynastic histories relate that the legendary doctor Hua Tuo (110-207) employed a formula called mafeisan to render his patients insensible prior to cutting them, even opening up their abdomens to excise rotting flesh and noxious accumulations. Some scholars have hypothesized that mafeisan (literally “hemp-boil-powder) may have contained morphine or cannabis (ma), but its ingredients remain a mystery. A text attributed to the twelfth-century physician Dou Cai (ca. 1146) recommended using a mixture of powdered cannabis and datura flowers (shan qie zi, also called man tuo luo hua) to put patients to sleep prior to moxibustion treatments, which in this text could involve a hundred or more cones of burning mugwort placed directly on the patient’s skin. Wei Yilin’s recipe provides important additional textual evidence for a tradition of anesthetic formulas based on toxic plants, one that was clearly in circulation long before he wrote it down.

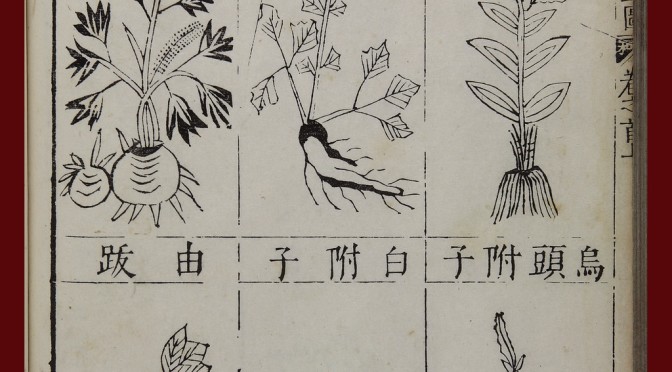

At least as far back as the Divine Farmer’s Classic of Materia Medica(3rd c.), medical authors had described aconite as highly toxic (for contemporary Roman views of aconite, see blogpost by Molly Jones-Lewis). In the right hands, however, aconite was a powerful drug, and part of the Chinese practice of using poisons to cure (see blogpost by Yan Liu). Warm and acrid, aconite could drive out pathogenic wind and cold from the body, break up stagnant accumulations, and invigorate the body’s vitalities. In the language of Chinese yin-yang cosmology, it nourished yang—all that was active, heating, external, and ascending. The main aconite root was considered more toxic than the subsidiary roots (designated by the separate name fu zi, “appended offspring”), and the wild form was more potent than the cultivated variety.

Wei’s numbing recipe consisted of 13 plant ingredients, including the main roots of both wild and cultivated (Sichuanese) aconite, along with drugs known as good for treating wounds:

Young fruit of the honey locust (zhu yao zao jiao)

Momordica seeds (mu bie zi)

Tripterygium (zi jin pi)

Dahurian angelica (bai zhi)

Pinellia (ban xia)

Lindera (wu yao)

Sichuanese lovage (chuan xiong)

Aralia (tu dang gui)

Sichuanese aconite (chuan wu)

Five taels each[1]Star anise (bo shang hui xiang)

“Sit-grasp” plant (zuo ru), simmered in wine until hot

Wild aconite (cao wu)

Two taels eachCostus (mu xiang), three mace

Combine the above ingredients. Without pre-roasting, make into a powder. In all cases of crushed or broken or dislocated bones, use two mace, mixed into high quality red liquor.

Wei most likely learned this formula from his great-uncle Zimei, a specialist in bonesetting and wounds. Its local origins are also suggested by its use of zuo ru, literally “sit-grasp”, a toxic plant whose botanical identity is unclear. However, according to the eighteenth-century Gazetteer of Jiangxi (Jiangxi tong zhi), sit-grasp was native to Jiangxi, Wei’s home province, and was used by indigenes to treat injuries from blows and falls. While classical pharmacology focused on the curative effects of aconite, Wei’s anesthetic relied on aconite’s ability to stupefy and numb, while curbing its ability to kill. If an initial dose failed to make the patient go under, Wei said, the doctor could carefully administer additional doses of wild aconite, sit-grasp herb and the datura flower.

In subsequent centuries, as medical texts proliferated, we find additional examples of numbing medicines that employed aconite, datura, and other toxic plants, employed when setting bones and draining abscesses, and to numb injured flesh before repairing tears and lacerations to ears, noses, lips, and scrotums. Such manual and surgical therapies are an integral part of the history of healing in China.

Yi-Li Wu is a Center Associate of the Lieberthal-Rogel Center for Chinese Studies at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (US) and an affiliated researcher of EASTmedicine, University of Westminster, London (UK). She earned a Ph.D. in history from Yale University and was previously a history professor at Albion College (USA) for 13 years. Her publications include Reproducing Women: Medicine, Metaphor, and Childbirth in Late Imperial China (University of California Press, 2010) and articles on medical illustration, forensic medicine, and Chinese views of Western anatomical science. She is currently completing a book on the history of wound medicine in China.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Wellcome Trust Medical Humanities Award “Beyond Tradition: Ways of Knowing and Styles of Practice in East Asian Medicines, 1000 to the present” (097918/Z/11/Z). I am also grateful to Lorraine Wilcox for directing me to the work of Dou Cai.

*****

[1] The weight of the tael (Ch. liang) has varied over time, but during Wei’s lifetime would have been equivalent to 40 grams. A mace (Ch. qian) is one-tenth of a tael.

An Examination of a Therapeutic Alliance: How the Acupuncture Experience Facilitates Treatment of the Modern Self Through the Methods of Intake and Self-Cultivation

Sharon Hennessey, DAOM, L.Ac.

Dr. Hennessey is Domain Chair of the Acupuncture Department at ACTCM @ CIIS with an interest in acupuncture research. She has published several articles in CJOM, and recently presented a poster at SAR’s Conference in 2015 and 2017. Her posters and articles can be viewed at sharonhennessey.com.

Abstract:

The concept of therapeutic alliance, i.e., the relationship between practitioner and patient, is identified as being historically rooted within the practice of traditional Chinese medicine. Within this context, this relationship is shown to serve the modern self — a recent construct favored in westernized industrial countries. While tracing the rise of the modern self, the value and limitations of this construct are evaluated.

In this essay both the acupuncture intake, comprised of ten questions, and the practice of the Chinese self-cultivation techniques are analyzed: the intake procedure as an effective therapy and practitioner self-cultivation as a source for patient inspiration. By re-appropriating archaic methods, Chinese medicine practitioners can guide patients in the formation of a valuable personal narrative to address a construct of modernity.

Key words:

acupuncture narrative, human potential, Yang Sheng self-cultivation.

An Archeological Discovery

Ancient Chinese culture may have eschewed the individual, but in the practice of Chinese medicine there has always been an emphasis on treating idiosyncratic pathologies, unique to each person. Elisabeth Hsu, in chapter 2 of Innovation of Chinese Medicine, describes twenty-five such medical case histories found in the biography of a Han doctor recorded in about 90 BC. Hsu asserts that illness was designated by the term bing rather than the term ji. Her investigation revealed that apart from other meanings, bing frequently referred to the emotional state of a distressed or aggrieved person, suggesting that bing referred to the mind-emotion-body complex.1 This concept of individualism, buried in Chinese medicine, functioned as a release valve for strictures in traditional Confucian culture, indicating a nod to the individual through pathology.

By using this strategy today, the modern acupuncture practitioner may covertly treat a wide range of disharmonies that effect the psychological or metaphysical through the medium of the physical body.

Evolution of the Modern Self

Once upon a time we were all part of a family, congregating within a community or tribe, bounded by rules and traditions that guided every aspect of our lives. But industrialization and other extraordinary successes of capitalism eventually managed to devastate these traditions and erode our connection with the past.

As now experienced, the concept of self is a unique and recent construct that has emerged in the past century, launching each individual on a quest for personal meaning that had been previously supplied by traditional communities. Add to that the Nietzschean demise of the creator, the startling new world of physics, and the material excess of capitalist production, there emerged from the divan of Sigmund Freud and other psychologists a new kind of self. In the BBC documentary, Century of the Self, Adam Curtis examines how we have moved from the ‘citizens with needs’ to ‘consumers with desire’. In this documentary, Curtis deconstructs how the Freudian concept of ‘unconscious’ desire was harnessed to the new business of marketing consumer goods, encouraging the emergence of a singular individual. This new self re-examined the constraints that had previously bound it to the precepts of religion and other dogma.

Jan Sloterdijk’s You Must Change Your Life describes our “withdrawal from this collective identity” as a directive demanding that all individuals must now stand beside themselves a priori, living their lives in front of the mirror, or function as actors of everyday life.2 He decrees that we were once part of a collective unity, bounded by religion, tradition, and family that functioned as additional immune system by guiding, signifying, and protecting us.2 Now, with only our self-created psyche to protect or direct us, humanity must face the numerous onslaughts of circumstance alone.

Christopher Macann states: “Ontological psychology ceases to be what Kant took it to be: a spurious deduction of the immortality of the soul from the principle of self-identity”3, and becomes instead what might be called a doctrine of self-actualization, a phrase made famous in Maslow’s Psychology of Being.”4 Maslow describes self-actualization as “….what a man can be, a man must be…It refers to the desire for self-fulfillment, namely, to the tendency for him to become actualized in what he is potentially. This tendency might be phrased as the desire to become more and more what one is, to become everything that one is capable of becoming.”5

Authoring the Self or How to Live a Meaningful Life

The self has now become a center for experimentation and authorship. For a meaningful life, experiences must be accumulated and curated, and the personal narrative becomes a centerpiece for communication. Individual stories serve as guideposts for inspiration and transcendence in much the same way as The Confessions of Saint Augustine did 1700 years ago.2 Self-involvement is not new to western history, but it was traditionally used to serve as an example at the demand of some greater authority. Augustine’s Confessions are an early version of a transformational life story that permeates Hollywood dramas and soaps.

For the multitudes, the self-portrait, particularly illustrated by Rembrandt’s more than 90 painted images of himself, is now the “selfie”—a self that is not under the control of some special aegis. It is especially unsettling to many social critics, who claim it is a short jump from selfie to selfish. Great moral opprobrium is attached to this concept of self. Critics see self-involvement as shedding important shared traditions that have served to organize people or, in a spiritual context, preferring the self to the creator or the originator of that self. But this new self, while, yes, prideful and actively undermining tradition, still requires tending and guidance.

Jumping forward to our new, service-oriented economy, many kinds of practitioners are now engaged in mapping the ontology for this new individual self through the medium of the personal narrative. This new self has spawned a huge service industry that caters to its development, refinement, and care. This is important because other cultural institutions that once cultivated, sheltered, and groomed this aspect of our psyche are in retreat.

The Chinese Medicine Intake: The Practitioner Helps the Patient Write a Narrative

In my own specialty, acupuncture, the patient is encouraged to build their personnel narrative based on the ten intake questions, which provides an organizational template for their story. As the patient describes their digestion, sleep patterns, urination, breathing, and any other subjective sensations they may wish to include, these ten questions serve as a type of somatic confessional, whereby the patient is able to transpose their psychological and metaphysical anxiety into simple and comprehensible evaluation of autonomic vegetative functions. Rather than the soul or psyche, these functions then become the object of transformation. By the simple principle of adjusting the flow, intake, and expulsion of fluids, gases, and solids, the individual can be tuned to perform at a higher level.

In a secular world there is the obvious benefit to only adjudicating somatic function. Many pejorative moral and psychological implications can thus be averted, while such vegetative functions are modified or streamlined to a superior level of performance.

This strategy of using Chinese medicine to treat the somatic body by addressing the psyche is oddly akin6 to the James-Lange Theory of Emotion. This theory was put forth in 19th century initially by American psychologist and theosophist William James and later, separately, by Danish physician Carl Lange. In this theory, physiological changes actually precede emotions. The subjective emotion is experienced because of the underlying physiology: our autonomic nervous system generates the physiological events that we associate with an emotion such as heart rate, perspiration, dry mouth, muscular tension. This theory suggests that emotions are a result of physiology rather than the cause.6 The autonomic nervous system is primarily unconscious, associated with activating the flight or fight response. But new research also shows that the sympathetic nervous system is “part of a constant regulatory machinery that keeps body functions in a steady state equilibrium.”7

It has been recently demonstrated that the sympathetic nervous system and the hypo-pituitary axis are activated by antigenic activity. Local immune cells inform the central nervous system and vice versa; the door swings both ways. New research in bioelectronics suggests that inflammation can be suppressed by stimulating the vagus nerve with electrical impulses. The standard of care associated with inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, or other insidious autoimmune conditions, might very soon incorporate vagal stimulation. Increasing vagal tone can also be taught by using the biofeedback technique.8,9 Hence, research science is verifying that the underlying soma is an effective pathway to modulate the psyche and vice versa.

In a study (to be published) by Randy Gollub et al., a patient’s experience of pain relief was correlated to their perception of being cared for with empathetic understanding. Patients were asked to evaluate the level of interest shown by their practitioner. Results demonstrated that their pain relief was enhanced by practitioner empathy. 10

A trial designed by Ted Kaptchuk, presents the notion that the patient’s narrative about self is fundamental to their health. He discusses and demonstrates how a practitioner perceives a patient affects the outcome of their health.11 This study of patients with irritable bowel syndrome randomly divided them into three groups. Group one was put on a waiting list. Group two received placebo treatment from a disinterested clinician. The third group got the same placebo treatment from a clinician who asked them questions about symptoms, while describing the causes of irritable bowel and displaying optimism about them overcoming their condition. Not surprisingly, the health of those in the third group improved the most.

The Golub and Kaptchuk studies demonstrate the value of practitioner involvement. In recording the patient’s subjective narrative, practitioner empathy becomes part of substrate that influences the acupuncture patient’s outcome.

Acupuncturists stress which foods to eat, the temperature of the food to be consumed, how much to drink, what to drink, when to sleep, when to rise, how to dress, how often to have sexual intercourse, or how to massage internal organs. For patients who have never observed their bodily functions, discovering that the shape of a stool or the color of urine or nose phlegm can be a window into the interior can have profound effect on self-reflection. In a secular world, Chinese medicine provides support and instruction similar in some ways to the dietary and lifestyle guidelines once administered by other belief systems.

The acupuncture intake and diagnosis that generates this personal narrative with its pastiche of authentic Taoist and Confucian phrases represents an antique system of healing. This also can function successfully today as an intact nonreligious construct for evaluating the pilgrim/patient’s transcendent progress on their journey with their self, stressing behavior over belief.

Evolution of Self–Cultivation

For Maslow, levels of self-actualization are the peak levels achieved by an individual. Often an evolved individual can by example pull the rest of humanity upward toward a higher level of proficiency or consciousness.

In his essay, The Neurology of Self-Awareness, Ramachandran suggests that mirror neurons have played a critical role in learning through imitation rather than trial and error, along with our strong ability to empathize. He proposes that extraordinary human progress, in which self-awareness is fundamental, is the result of the interplay of these mirror neurons.12 He also posits that because of mirror neurons, humans have the uncanny ability to imitate each other and understand each other’s feelings, “setting the stage for a complex Lamarckian or cultural inheritance that characterizes our species.”12

Rizzolatti discovered back in 1996 that mirror neurons are the pre-motor neurons that fire when a primate performs some object-directed actions, such as grasping, tearing, manipulating, or holding but also when the animal watches someone else perform the same actions.13

Additionally, it is not just the repetition of one but repetition of many, imitating and competing, that drives us forward. Take the simple example of the marathon: in 1921, best time was 3 hours and 18 minutes; in 2014, best time was 2 hours, 2 minutes and 57 seconds.14 This has been achieved over the span of many years, through the accumulated effort of many runners, competing against each other, and shaving the time, second by second, year by year. Each competed to be the best, inspired by and imitating the competitor whom they followed, and tended and coached by those who made running a practice.

This sort of consciousness-raising effort that pervades human behavior is described by Jan Sloterdijk in You Must Change Your Life. He lauds the Nietzschean doctrine of combining practice with cumulative knowledge or education and designates practicing and training as an original and uniquely human path, especially in seeking to transcend the self.2 Through Sloterdijk‘s lens, training, peak experiences, and performance crystallize the human experience, while conscious measurement, observation, and skill refinement are reflected in learning and practice.

Sloterdijk comments that such training and practice systems formed the core of Platonism, Brahmanic training, and Taoist alchemy and martial arts, guiding adepts up ‘the vertical wall of achievement’ in superhuman spiritual and athletic extremes that have shaped the image of what human potential can be.2

Chinese Practice and Self-Cultivation

In ancient China, Taoism embraced the belief that through breath and meditation they could transform their lives, by reaching for immortality. Joseph Needham describes how in ancient China the physiological alchemists believed they could “master their neuro-muscular coordination, and sexual activity as part of the Tao.”15 He describes such activities, listing how this was accomplished by employing respiratory exercises, counting heartbeats, experiencing the movement of inner qi, and using a myriad of other special techniques, which were designed prolong longevity or restore youth by internally transforming the practitioner.15 These early Taoists exercises evolved into complicated styles of self-cultivation.

During the early Han period, around 200-100 BC, medical understanding of the inner body was changing. By the time the Huang de Nei Jing was compiled, there was a formal system of channels known as the jing luo, which allowed different types of qi to circulate.1

Medical technology was also changing. Fine filament needles became the preferred method of treatment.16 The practitioner was guided by the Su Wen and Ling Shu on how to perform this new inner practice. He was encouraged to gather his qi, employing techniques of self-cultivation that acupuncture students are still taught to imitate today. Metaphors in the Su Wen, such as “use the hand as if holding a tiger” or “pouring over a deep abyss,” coach the practitioner on how to proceed in treatment.

Technique was conflated with rectitude and moral character, instructing the practitioner to influence the spirit of the patient or proceed to a deeper metaphysical exchange, using the needle as an instrument of transmutation.16 These special skills represented the fruits of self-cultivation for the practitioner.

By focusing on self-manipulation of qi and self-improvement in technique, acupuncturists have become default practitioners of Yang Sheng self-cultivation

skills.1 Modern Chinese medicine has become an odd mix of the esoteric internal practice methods combined with modern physiology. By simply reading through a list of continuing education courses or the advanced curriculum at institute of traditional Chinese medicine, this obsession with obscure Taoist practices can easily be verified.

Pursuing a practice under the guidance of a Chinese master, whose particular lineage defines their curriculum vitae, is the equivalent to pursuing a board certification in another profession. Even if personally refraining from a deliberate practice of self-cultivation, acupuncture students are exposed to such practices through curriculum requirements. It is inculcated in the rhythm of learning in a professional school, where either qi gong or tai chi are combined with esoteric poetry about nature.

It is normal to find a student of acupuncture involved in a deep meditative performance exercise such as tai chi. Mastery of practice-related performance is expected of these students. In this profession, self-cultivation and skill development go hand in hand; other medical professionals are not expected to harmonize their qi, learn mystical movements such as tai chi, or root their being, before interacting with their patient. The skills of self-cultivation as both a healing art and a moral virtue are embedded in Chinese medicine. This imbues the practitioner with leadership qualities that occur in other training modes such as sports, arts, or religion. The modern patient, typically lacking in ritual signifiers for lifestyle direction, can thus benefit from this personal example of their practitioner.

Conclusion

Western treatments based on statistical patterns and board declarations that direct standards of care often negate or ignore an individual’s metaphysical sense of being. In the context of eastern and western cultural norms, western culture employs treatment standards that are ironically more aligned with the statistical whole, whereas traditional Chinese medicine, aligned with a rigid Confucian social structure, embraces the individual. In this example of cultural syncretism, acupuncture offers the modern self the care and understanding that it currently lacks in the territory of western evidence-based treatment.

Despite being anchored in traditional principles of Taoist and Confucian philosophy, Chinese medicine is able to address the modern concept of self by creating a distinct diagnostic template for the treatment of each patient. This narrative template teaches individuals to observe and measure their soma in a practical, effective way against an intact system that encompasses philosophical underpinnings that reflect every aspect of patient behavior. It is composed of understandable natural metaphors that generally resonate well with the patient and can be transposed into simple behavioral modification.

As part of traditional culture, both the narrative and techniques of self-cultivation are able to furnish individual guidance and performance-activated behavior that are often lacking in both western therapy and modern cultural norms. When scientists try to evaluate the efficacy of the acupuncture treatment, they often fail to comprehend the value of these methods: the intake, which varnishes the diagnosis with a veneer of empathy, and examples of self-cultivation, which represent internal strength achieved through moral refinement. Together, these two essential components of an acupuncture treatment may contribute monumentally to a therapeutic alliance that successfully enhances the patient’s outcome.

References:

- Ed. by Elisabeth Hsu, Innovation in Chinese Medicine, Needham Research Institute, Cambridge University Press, 2001; p. 16.

- Peter Sloterdijk, You Must change Your Life, Polity Press; 2013. pp. 211, 215, 322, 199.

- Referring to the Cartesian Objective

- Maccan, Being and Becoming: https://philosophy now.org/issues/61

- A.H.Maslow (1943); A Theory of Human Motivation, Originally published in Psychological Review, 50, p.370-396. http;//psychclassics.yorku.ca/Maslow/motivation.ht

- https:Wikipedia.org/wiki/James-Lange_theory

- http://medscape.com; Medscape: Arthritis Research & Therapy; Georg Pongratz; Rainer H Straub; The Sympathetic Nervous Response in Inflammation.

- http://www.newyorktimes.com: Michael Beharmay, Can the Nervous System Be Hacked?; Mar. 23, 2014.

- Torres-Rosas R, Yehia G, Peña G, Mishra P, del Rocio M, Ulloa L, et al. Dopamine mediates vagal modulation of the immune system by electroacupuncture. Nature Medicine. 20, 291–295 (204) doi:10.1038/nm.3479

- Mawla I, Gerber J, Delibero S, Oriz A, Protsenko E, Gollub R. Oral Abstract, Therapeutic Alliance between Patient and Practitioner Is Associated with Acupuncture Analgesia in Chronic Low Back Pain, Society for Acupuncture Research, 2015 Conference program, Boston, MA, USA, 11/12-13, 2015 , #SAR2015.

- T J Kaptchuk; Components of placebo effect: Randomised controlled trial in patients with irritable bowel syndrome; BMJ.April2008;336:999 doi:10.1136/bmj.39524.439618.25.

- Ramachandran V. [1.1.09]; Conversation: (title) Mind; Self Awareness: The Last Frontier; E. edge.org.

- Marco Iacoboni, Istvan Molnar-Szakacs, Vittorio Gallese, Giovanni Buccino, John C Mazziotta, and Giacomo Rizzolatti; Grasping the Intentions of Others with One’s Own Mirror Neuron System; Published: February 22, 2005; DOI:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030079

- https:/www.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marathon;_world_record_progression

- Joseph Needam, Volume V, Science and Civilisation in China: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 5, Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Physiological Alchemy, Science and Civilisation in China, Volume V:5; Cambridge University Press,1985; p. XXVIII, Introduction., p. 29

- Vivienne Lo, Spirit of Stone: Technical Considerations in the Treatment of the Jade Body; Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London Vol. 65, No. 1 (2002), pp. 99-128, Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of School of Oriental and African Studies; Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4145903

Classical Formula Powders: Dosage and Application

Treatment periods are rarely discussed in classical Chinese medical literature. While classics like the Shanghan Lun meticulously describe formula preparation and administration over the course of a day, the number of days a formula should be used for is never plainly described. Due to this ambiguity, many physicians apply a saying that originates in the Huangdi Neijing to classical formula use, “after one dose one knows, after two doses there is resolution.”[i]

However, by examining powder and pill formula dosage, we can gain more specific insight into classical treatment timeframes. Whereas with liquid decoctions the written herb weights compose a single day’s worth of formula, with powders the daily dose is fixed at a few grams and the herb weights define a formula’s projected treatment period.

This article is an exploration into the treatment periods and patterns for four foundational classical formula powders, accurate weights and measures based on Han period archeological evidence, and the drinks traditionally used to aid powder consumption. The goal is to provide insight into how and why classical clinicians used medical powders.

Classical Weights

A liang (兩) is the core unit of weight used in classical Han dynasty formulas. Though there has been some debate as to the exact weight of a classical liang throughout Chinese history, and a great deal of inaccuracy in modern texts, recent archeological findings indicate that a liang weighed between 13.8 and 15.6 grams. Contemporary doctors in mainland China generally simplify a classical liang’s weight to 15g. A classical Liang can be subdivided into 24 zhu (銖) or four fen (分). 16 Liang combine to make one jin (斤)[iii]. The table below describes the weight of each measurement unit:

Table 1. Han Period Weight Units

| Measure Unit | Approximate Weight | Simplified Weight |

| Jin 斤 | 220.8g to 249.6g | 240g |

| Liang 兩 | 13.8g to 15.6g | 15g |

| Fen 分 | 3.45g to 3.9g | 3.75g |

| Zhu 銖 | 0.575g to 0.65g | 0.625g |

Single doses of powdered formulas were most commonly dosed by heaping powder onto a fangcunbi (方寸匕, Square Inch Spoon) or a qianbi (錢匕, Coin Spoon). The cun (寸), a classical unit of measurement, is 2.32cm long.[iv] Therefore, a square cun measures 5.4 cm2 in area. The Zhongyao Da Cidian (中藥大辭典, Great Encyclopedia of Chinese Medicine) states that a fangcunbi weighs 2g for metal and stone powders and 1g for plant powders. However, the actual tested weights are somewhat heavier, causing researcher Li Yuhang (李宇航) to conclude that plant powders should be dosed at 1-2g and mineral powders at 3-4g[v]. A portion of his findings is translated on the following table:

Table 2. Actual Fangcunbi Powder Weights

| Formula | Actual Weight |

| Wu Ling San 五苓散 | 1.59g |

| Muli Zexie San 牡蠣澤瀉散 | 1.27g |

| Banxia San 半夏散 | 1.46g |

| Sini San using Baishao 四逆散(白芍) | 1.66g |

| Sini San using Chishao 四逆散(赤芍) | 1.68g |

| Chishizhi (in Taohua Tang) 赤石脂(桃花湯) | 3.31g |

| Wenge San 文蛤散 | 3.33g |

The qianbi dose was measured using the Han Dynasty wuzhuqian (五銖錢, five zhu coin). The coin’s radius measures 2.5cm and it has an approximately 1 cm2 square hole in the center. Assuming a finger is used to plug the square hole in the center of the coin when used as a scoop, the area measures 4.9 cm2, giving it roughly 10% less area than the fangcunbi.

For the purposes of this article, I simplified unknown formula powder weights to 1.66g per dose for a fangcunbi and 1.5g for a qianbi. Given that most formulas suggest three daily doses this works out to 5g total per day for the fangcunbi and 4.5g per day for the qianbi.

Intake Methods

Classically, powders are stirred into a warm liquid and drank. The choice of liquid gives additional insight into the formula’s purpose and should be considered an essential part of powdered formula construction. The main liquids used for powder administration in the Shanghan Lun and Jingui Yaolue are baiyin (白飲, the water from boiled rice[vi], also called miyin 米飲), maizhou (麥粥, wheat porridge), jiangshui (漿水, fermented millet water), jiu (酒 rice wine, likely analogous to modern huangjiu 黃酒) and water. In formulas that don’t specifically mention what drink to use, Ge Hong and Sun Simiao suggest that any of the above can be used[vii], presumably leaving the choice of liquid assistant to the practitioner.

Table 3. Liquid Assistants for Powder Administration

| Liquid | Function | Formulas |

| Baiyin (白飲, boiled rice water) | Sweet, balanced. Strengthens earth harmonizes the middle qi, separates clear from turbid, generates fluids;stops thirst; promotes urination. | Sini San, Wu Ling San, San Wu Xiao Bai San, Muli Zexie San.Rice is also used in Baihu Tang, Taohua Tang, and Zhuye Shigao Tang. |

| Maizhou (麥粥, wheat porridge) | Sweet, slightly bitter, cool. Eliminates heat, stops thirst and dry throat, promotes urination, nourishes liver qi. | Zhishi Shaoyao San, Baizhu San (modification).Wheat is also used in Gan Mai Dazao Tang. |

| Jiangshui (漿水, fermented millet water) | Sweet, sour, cool. Regulates the stomach, dissolves food obstructions, stops thirst. | Chixiaodou Danggui San, Shuqi San, Banxia Ganjiang San, Baizhu San (modification).Jiangshui is also used in Zhishi Zhizichi Tang. |

| Jiu (酒, rice wine) | Bitter, acrid, warm. Invigorates the channels, unblocks obstruction syndrome, warms the blood, scatters blood stasis. | Danggui Shaoyao San, Danggui San, Baizhu San, Tianxiong San, Zishi Han Shi San, Tuguagen San. |

A Selection of Powdered Formulas

According to Dr. Li Yuming,[viii] Zhang Zhongjing uses internal powdered formulas primarily to treat diseases of the lower jiao, especially recalcitrant conditions that involve blood deficiency and or fluid accumulation. Below I have selected four representative formulas that each demonstrate a specific lower jiao pathology and can be considered foundational building blocks for individualized powdered formula construction.

Sini San 四逆散, Frigid Extremities Powder

| SiniSan | SHL Text Weight | Gram Weight |

| Zhi Gancao 炙甘草 | 10 Fen分 | 37.5g |

| Zhishi 枳實 | 10 Fen分 | 37.5g |

| Chaihu 柴胡 | 10 Fen分 | 37.5g |

| Shaoyao 芍藥 | 10 Fen分 | 37.5g |

| Total Formula Weight | 40 Fen分 | 150g (138g-156g) |

| Single Dose Weight | 1 Fangcunbi | 1.66g-1.68g |

| Daily Dose Weight | 3 Fangcunbi | 5g (4.98g-5.04g) |

| Treatment Period | 30 Days (27.3-31.3days) | |

| Administered With | Baiyin白飲 (Boiled Rice Water) | |

Sini San treats Liver qi stagnation that manifests with cold hands and feet, possibly with cough, palpitations, inhibited urination, abdominal pain, or diarrhea with tenesmus, emotional distress, depression, chest and rib distention or pain, or breast distention pain, with a white tongue coat, and a thin wiry pulse.[ix]

According to the Shennong Bencao Jing (《神農本草經》The Divine Husbandman’s Classic of Materia Medica), Chaihu’s bitter, balanced nature has the ability to eliminate knotted qi and food accumulations from the GI tract.[x] Zhishi’s bitter, cool, slightly acrid and sour nature assists Chaihu by breaking up stagnant qi, reducing distention and pain from accumulation and directing the qi of the GI tract downwards. Shaoyao’s bitter, sour and slightly cool nature nourishes the liver, preserves yin, and according to the Mingyi Bielu (《名醫別錄》Miscellaneous Records of Famous Physicians) eliminates blood stasis, expels water, and benefits the bladder and intestines.[xi] Zhi Gancao’s sweet, warm nature nourishes the middle qi. Rice water’s bland, sweet and balanced nature is used to administer the formula to build thin fluids, regulate fluid metabolism, and benefit the spleen and stomach.

The Sini San pattern shows signs of dryness, blood deficiency, qi knotting, and food accumulations in the GI tract, and resultant lower jiao yang qi depression. The formula is overall cool and bitter, with hints of acrid, sour, and sweet and should be considered a light purgative with elements of qi and blood building. Sini San’s light dose and ability to enter the lower jiao is aimed at slowly purging the intestines without stressing the body’s upright qi. Due to the purgative nature, caution should be used when exceeding the projected treatment period of 30 days.

Wu Ling San 五苓散, Five Poria Powder

| Wu Ling San | SHL Text Weight | JGYL Text Weight | Gram Weight |

| Zexie 澤瀉 | 1 Liang 兩 6 Zhu 銖 | 1Liang兩1Fen分 | 18.75g |

| Zhuling 豬苓 | 18 Zhu銖 | 3Fen分 | 11.25g |

| Fuling 茯苓 | 18 Zhu銖 | 3Fen分 | 11.25g |

| Baizhu 白術 | 18 Zhu銖 | 3Fen分 | 11.25g |

| Guizhi 桂枝 | ½ Liang兩 | 2Fen分 | 7.5g |

| Total Formula Weight | 4 Liang | 60g (55.2g-62.4g) | |

| Single Dose Weight | 1 Fangcunbi | 1.59g | |

| Daily Dose Weight | 3 Fangcunbi | 4.77g | |

| Treatment Period | 12 days (11.6 – 13.1 days) | ||

| Administered With | Baiyin白飲 (Boiled Rice Water) | ||

Wu Ling San treats a number of symptom patterns, all of which revolve around dampness accumulation in the lower jiao resulting in some degree of yang qi depression and heat. The primary acute pattern manifests with headache, low fever, irritability, aversion to cold, dry mouth and thirst, possibly with vomiting upon drinking, and urinary obstruction. Other variants include diabetic thirst and edema patterns.

Zexie, Zhuling, and Fuling’s overall bland and cool natures act to leach out dampness, promote urination, and gently clear lower jiao heat. Baizhu’s bitter warm nature strengthens the spleen by drying dampness and dissolving food and phlegm liquids[xii]. Guizhi’s acrid warm nature disperses yang and promotes the movement and ascent of yang out of the lower jiao. Rice water’s bland, sweet and balanced nature is used to administer the formula to build thin fluids, regulate fluid metabolism, and benefit the spleen and stomach.

When taking the Wu Ling San the patient is advised to drink plenty of warm water and that the condition will resolve through gentle sweating which indicates that upright qi has regained control of the surface. Presumably, the 12 day dose period is the expected term of resolution for the acute symptom pattern.

Danggui Shaoyao San 當歸芍藥散, Angelicae and Peony Powder

| Danggui Shaoyao San | JGYL Text Weight | Gram Weight |

| Danggui | 3 Liang | 45g |

| Shaoyao | 1 Jin | 240g |

| Fuling | 4 Liang | 60g |

| Baizhu | 4 Liang | 60g |

| Zexie | ½ Jin | 120g |

| Chuanxiong | ½ Jin (3 Liang*) | 120g (45g*) |

| Total Formula Weight | 43 Liang (38 Liang*) | 645g (593.4g – 670.8g)

570g* (524.4g – 592.8g) |

| Single Dose Weight | 1 Fangcunbi | ~1.66g |

| Daily Dose Weight | 3 Fangcunbi | ~5g |

| Treatment Period | 129days (118.7 days – 134.2 days)

114 days* (104.9 days – 118.6 days) |

|

| Administered With | Jiu 酒 (Rice Wine) | |

*One Jingui Yaolue version states a 3 liang dose for Chuanxiong, all other versions state ½ jin.

Danggui Shaoyao San primarily treats blood deficiency with fluid accumulation in the lower jiao resulting in abdominal pain or cramping. Though the pattern is more common among women, the formula can also be used for men. Other possible symptoms include rib distention or pain, lack of appetite, dizziness, emotional constraint, and weakness of the limbs with a pale tongue, white tongue coating, and a deep, wiry pulse.[xiii]

The formula is composed of two main elements: Danggui, Chuanxiong and Shaoyao to nourish the blood and gently disperse blood stasis; and Fuling, Zexie, and Baizhu to regulate water metabolism, dry dampness, promote urination and fortify the spleen. Together the two groups somewhat resemble a combination of Wu Ling San and Sini San but with a greater focus on blood level movement and nourishment. To further promote blood movement, rice wine’s acrid, bitter and warm nature is used to administer the formula. The Mingyi Bielu notes that Rice Wine has the specific ability to circulate a medicine’s strength[xiv] by unblocking the channels and invigorating the vessels.

While the formula is best known for treating acute stomach cramping during pregnancy, modern text books urge cautious use during pregnancy, “specifically because too high a dosage of Chuanxiong Rhizoma can affect the fetus, particularly in mothers who have deficient and weak Kidney qi”.[xv] The question of whether Danggui Shaoyao San’s daily dose of Chuanxiong at 0.93g is considered high must be left to the practitioner and further research. But clearly, it was classically thought of as a safe formula as it was dosed for around four months of use during pregnancy and is suited for long term blood and fluid regulation in the lower jiao.

Chixiaodou Danggui San 赤小豆當歸散, Adzuki and Angelicae Powder

| Chixiaodou Danggui San | JGYL Text Weight | Gram Weight |

| Chixiaodou (adzuki bean, sprouted and dried) | 3 Sheng* | 510g |

| Danggui | 10 Liang** | 150g |

| Total Formula Weight | 660g | |

| Single Dose Weight | 1 Fangcunbi | ~1.66g |

| Daily Dose Weight | 3 Fangcunbi | ~5g |

| Treatment Period | 132 days | |

| Administered With | Jiangshui 漿水 (Fermented Millet Water) | |

* A Sheng is a unit of volume that measures approximately 200ml.

** Some Jinggui Yaolue versions write 3 liang, others write 10 liang.

Chixiaodou Danggui San treats damp heat in the lower jiao which can lead to hemorrhoids, anal prolapse, excessive menstrual bleeding, ulceration, intestinal abscess, red eyes, rashes, irritability and other symptoms associated with damp head leading to blood toxicity presenting with a red tongue, yellow, greasy tongue coat, and rapid pulse.

Chixiaodou has a sweet/bland, slightly sour, and balanced nature, promotes urination, drains damp heat, stops bleeding and, as noted in the Shennong Bencao Jing, has the ability to expel the blood and pus from carbuncles and welling-abscess.[xvi] Danggui’s sweet, acrid and warm nature nourishes the blood, disperses stasis, and promotes the healing of sores. Fermented millet water is used to administer the powder and supports Chixiaodou by dissolving food accumulation and regulating the stomach with its sweet, sour, and cool nature.

Like Danggui Shaoyao San, Chixiaodou Danggui San has an intended dose period of around four months and aims to nourish blood in the lower jiao while simultaneously eliminating fluid accumulation. Chixiaodou, a common food in China, is a particularly safe medicine for the slow, long term elimination of damp heat and blood toxicity.

Conclusion

From the above formulas, we can clearly see that Zhang Zhongjing favored using powders for the long-term treatment of recalcitrant lower jiao and gastrointestinal diseases that present with mixed excess and deficiency patterns. According to the Jingfang Xiaopin (《經方小品》A Small Collection of Classical Formulas), powders and pills were used after a decoction formula had eliminated the primary pathogenic factors, presumably as a long term regulatory treatment, which could then be periodically assisted with decoction formulas.[xvii] Sun Simiao believed powders were appropriate for slowly driving out pathogens, particularly wind and damp obstructions with symptoms that come and go without a static location,[xviii] as is characteristic with many gastrointestinal disorders.

Unfortunately, formula powders are rarely used in the modern clinic. When used, they are often decocted as liquid formulas with little concern for difference in administration form or dose. I hypothesize that powdered formulas may offer a better, cheaper, safer, and more convenient treatment method for the long-term resolution of many gastrointestinal and other lower jiao associated disorders, especially when used in conjunction with periodic decoction formula treatments. As renewed interest in classical formula theory and application continues to grow in China and around the world I hope that modern practitioners will also renew research into formula powders for modern clinical use.

Endnotes

[i]《黄帝内经素问·腹中论篇第四十》云,“一剂知二剂已”。

[ii] 王付.经方用量秘旨. 人民军医出版社, 2015.62-64,98-100

[iii]《汉书·律历志·权衡》云,“权者,铢、两、斤、钧、石也……一龠容千二百黍,重十二铢,两之为两,二十四铢为两,十六两为斤”。

[iv] 李宇航.《伤寒论》方药剂量与配伍比例研究. 人民卫生出版社, 2015. 64

[v] 李宇航.《伤寒论》方药剂量与配伍比例研究. 人民卫生出版社, 2015. 68

[vi] 朱西杰、晋学仁、樊恒茂. “《伤寒论》“白饮”新解”,来源:《国医论坛》2000年第02期

[vii]《千金要方·论服饵第八》云,“凡服丸散,不云酒水饮者,本方如此,是可通用也”。《肘後備急方·華陽隱居《補闕肘後百一方》序》云,“凡下丸散,不雲酒水飲者,本方如此,而別說用酒水飲,則是可通用三物服也”。

[viii] 李宇铭.伤寒治内方证原意. 中国中医药出版社, 2014.

[ix] 王付《历代经方方论》.人民军医出版社, 2013. 515

[x]《神农本草经》云,“柴胡味苦平,主心腹,去肠胃中结气,饮食积聚,寒热邪气,推陈致新”。

[xi]《名医别录》云,“芍药味酸微寒有小毒,主通顺血脉,缓中,散恶血,逐贼血,去水气,利膀胱、大小肠,消痈肿,时行寒热,中恶,腹痛,腰痛”。

[xii]《神农本草经》云,“消食”。《名医别录》云,“消痰水……消谷嗜食”。

[xiii] 王付《历代经方方论》.人民军医出版社, 2013. 574

[xiv]《名医别录》云,“酒,味苦甘辛大热有毒,主行药势,杀邪恶气”。

[xv] Bensky Chinese Herbal Medicine – Formulas & Strategies, 2nd Ed. page 588

[xvi] 《神农本草经》云, “ 味甘、酸,平。主下水肿,排痈肿脓血。生平泽”。

[xvii]《小品方·述看方及逆合备急药决》云,“病源宜服利药治取除者服汤之后宜将丸散也时时服汤助丸散耳”

[xviii]《千金要方·论诊候第四》云,“散能逐邪风气湿痹表里移走居无常处者散当平之”

Introduction to Ruesi Dat Ton

Ruesi Dat Ton and the Foundations of Thai Massage

Reusi Dat Ton is a little known aspect of traditional Thai healing and culture. It consists of breathing exercises, self-massage, acupressure, dynamic exercises, poses, mantras, visualization and meditation.

“Reusi” in Thai, from the Sanskrit Rishi, is an Ascetic Yogi or Hermit. “Dat” means to stretch, adjust or train. “Ton” is a classifier used for a Reusi and also means oneself. So “Reusi Dat Ton” means the Hermit’s or Yogi’s self-stretching or self-adjusting exercises. Reusis were also known as “Jatila,” Yogi,” and “Chee Prai.” The Reusis were custodians and practitioners of various ancient arts and sciences such as: tantra, yoga, natural medicine, alchemy, music, mathematics, astrology, palmistry, etc. They have counterparts in many ancient cultures, such as: the Siddhas of India, the Yogis of Nepal and Tibet, the Immortals of China, the Vijjadharas of Burma and the Cambodian Eysey (from the Pali word for Reusi, Isii).

There are different Reusi traditions within Thailand. There is a Southern Thai/Malay Tradition, a Northeastern Thai/Lao Tradition, a Central Thai/Khmer Tradition and a Northern Thai/Burmese/Tibetan Tradition. In Thailand, there are Reusis as far South as Kanchanaburi Province who follow the Northern Thai/Burmese/Tibetan Reusi Tradition.

A typical Reusi Dat Ton program would begin with breathing exercises and self-massage, followed by dynamic exercises and poses (some of which involve self acupressure) and finish with visualization, mantras and meditation. The exercises and poses of Reusi Dat Ton range from simple stretches which almost anyone could do, to very advanced poses which could take many years to master.

Some of the Reusi Dat Ton techniques are similar to or nearly identical to some techniques in various Tibetan Yoga Systems, particularly “Yantra Yoga,” “Kum Nye” and the Tibetan Yoga Frescoes from the Lukhang Temple behind the Potala Palace in Lhasa Tibet. (See Norbu, Tulku and Baker) For example; some of the self massage techniques, exercises, poses, neuromuscular locks (bandhas in Sanskrit,) breathing patterns, ratios, visualizations and the way in which male and female practitioners would practice the same technique differently are almost identical. It is possible that Reusi Dat Ton and some of the Tibetan Yoga Systems are derived from a common source, which Rishis brought with them as they moved down the Himalayan foothills into Southeast Asia.

According to the Reusi Tevijo Yogi “The foundation and key to Traditional Thai massage is Reusi Dat Ton. Ancient Reusis, through their own experimentation and experience, developed their understanding of the various bodies (physical, energetic and psychic, etc.) They discovered the postures, channels, points, the winds and wind gates within themselves. Later it was realized that these techniques could be adapted and applied to others for their healing benefit, which is

how Thai massage was developed. So, in order to really understand Thai massage, as a practitioner, one should have a foundation in Reusi Dat Ton and be able to experience it within oneself and then apply it to others. It is not only the roots of Thai massage but it also unlocks the method for treating oneself and maintaining one’s own health.” (Reusi Tevijo Yogi)

It is also interesting to note that there are many similarities between the Reusi Dat Ton “Joint Mobilization Exercises,” many Thai massage techniques and some of the Indian Hatha Yoga therapeutic warming up exercises (the Pawanmuktasana or wind liberating and energy freeing techniques.) There is even an advanced Hatha Yoga pose, Poorna Matsyendrasana, which compresses the femoral artery and produces the same effect as “opening the wind gate” in Reusi Dat Ton Self Massage and Traditional Thai massage. (Saraswati)

Reusi Dat Ton in Traditional Art

In Northeast Thailand, in Buriram province atop an extinct volcano sits the Ancient Khmer temple of Prasat Phnom Rung. Built between 900 and 1200AD, this temple is dedicated to the Hindu God Shiva. The pediment over the eastern doorway features a sculpture of an avatar of Shiva in the form of Yogadaksinamurti. According to the Department of Fine Arts “Yogadaksinamurti means Shiva in the form of the supreme ascetic, the one who gives and maintains wisdom, perception, concentration, asceticism, philosophy, music and the ability to heal disease with sacred chants.” Here “Shiva is dressed as a hermit with crowned headdress holding a rosary in his right hand, seated in the lalitasana position…surrounded by followers. There are figures below him that…represent the sick and wounded.” (Department of Fine Arts). All over the temple one can see additional carvings of Reusis engaged in various activities. In one carving of the “Five Yogis” (or Reusis) the central figure is the God Shiva in his incarnation as Nagulisa, the founder of the Pasupata sect of Shivaite Hinduism. The four yogis on his sides are followers of this Pasupata sect, which is still active today in Nepal.

In 1767, invading Burmese armies destroyed the old Thai capital of Ayutthaya. Soon after his coronation in 1782, the Thai King Rama I established a new capital in what is today Bangkok. He initiated a project to revive the Thai culture after the disaster of Ayutthaya. An old temple Wat Potharam, (popularly known as “Wat Po,”) was chosen to become the site of a new Royal temple

and formally renamed Wat Phra Chetuphon. Beginning in 1789, a renovation and expansion project was begun on the temple. King Rama I also initiated a program to restore and preserve all branches of ancient Thai arts and sciences including: medicine, astrology, religion and literature. As part of this project, medical texts from across the kingdom were collected and brought to be stored at Wat Po. The King also ordered the creation of a set of clay Reusi statues depicting various Reusi Dat Ton techniques.

This restoration project was continued by the Kings Rama II and Rama III. As part of this work, scholars compiled important texts on various ancient arts and sciences and created authoritative textbooks for each of these fields. In 1832, a project to etch the medical texts into marble tablets was begun. Medical theories regarding the origin and treatment of disease, massage charts and over 1000 herbal formulas were all recorded on the marble tablets. Gardens of medicinal herbs were also planted on the temple grounds. Thus, Wat Po was to become “a seat of learning for all classes of people in all walks of life” which would “expound all braches of traditional knowledge both religious and secular,” and serve as “an open university” of traditional Thai culture with a “library of stone.” (Griswold, 319-321)

By 1836, the clay Reusi Dat Ton statues created by order of King Rama I had deteriorated. To replace these, King Rama III commissioned the creation of 80 new Reusi Dat Ton statues. Each statue depicted a different Reusi performing a specific Reusi Dat Ton technique. For each statue there was a corresponding marble tablet upon which was etched a poem describing the technique and it’s curative effect. These poems were composed by various important personalities of the day. Princes, monks, government officials, physicians, poets, and even the King himself contributed verses. The original plan was to cast the statues with an alloy of zinc and tin, but unfortunately only the more perishable material stucco was used. The statues were then painted and housed in special pavilions. Over the years most of the original statues have been lost or destroyed. Today only about 20 remain and these are displayed upon two small “Hermit’s Mountains” near the Southern entrance of Wat Po. The marble tablets have been separated from their corresponding statues and are now stored in the pavilion Sala Rai.

Beginning in 2009, the casting of metal Reusi Dat Ton statues was begun. These new statues are gradually appearing in and around the Wat Po Massage School near the Eastern entrance of Wat Po. So now after almost 200 years, Wat Po will soon finally have it’s complete set of 80 metal Reusi Dat Ton statues as originally envisioned by King Rama III.

Textual Sources of Reusi Dat Ton

We may never know what, if any Ancient texts on Reusi Dat Ton may have existed and were lost when the invading Burmese armies destroyed the old Thai capital of Ayutthaya in 1767. Today, the closest thing to an original source text on Reusi Dat Ton is an 1838 manuscript commissioned by Rama III entitled The Book of Eighty Rishis Performing Posture Exercises to Cure Various Ailments. Like other manuscripts of the time, this text was printed on accordion like folded black paper, known in Thai as “Khoi.” This text, popularly known as the Samut Thai Kao features line drawings of the 80 Wat Po Reusi Dat Ton statues along with their accompanying poems. In the introduction, it states that Reusi Dat Ton is a “…system of posture exercises invented by experts to cure ailments and make them vanish away.” (Griswold, 321) This text is housed in the National Library in Bangkok. There are also other editions of this text housed in museums and private collections as well.

The Benefits of Reusi Dat Ton

In both the Samut Thai Kao and The Book of Medicine, the texts not only describe the techniques, but also ascribe a therapeutic benefit to each pose or exercise. Some poems describe specific ailments while others use Sanskrit Ayurvedic medical terminology.

Some of the ailments mentioned include; abdominal discomfort and pain, arm discomfort, back pain, bleeding, blurred vision, chest congestion, chest discomfort and pain, chin trouble, chronic disease, chronic muscular discomfort, congestion, convulsions, dizziness and vertigo, dyspepsia, facial paralysis, fainting, foot cramps, pain and numbness, gas pain, generalized weakness, generalized sharp pain, headache and migraine, hand discomfort, cramps and numbness, heel and ankle joint pain, hemorrhoids, hip joint problems, joint pain, knee pain and weakness, lack of alertness, leg discomfort, pain and weakness, lockjaw, low back pain, lumbar pain, muscular

cramps and stiffness, nasal bleeding, nausea, neck pain, numbness, pelvic pain, penis and urethra problems, scrotal distention, secretion in throat, shoulder and scapula discomfort and pain, stiff neck, thigh discomfort, throat problems, tongue trouble, uvula spasm, vertigo, waist trouble, wrist trouble, vomiting, and waist discomfort.

Some of the Ayurvedic disorders described in the texts include; Wata (Vata in Sanskrit) in the head causing problems in meditation, severe Wata disease, Wata in the hands and feet, Wata in the head, nose and shoulder, Wata in the thigh, Wata in the scrotum, Wata in the urethra, Wata causing knee, leg and chest spasms, Wata causing blurred vision, Sannipat (a very serious and difficult to treat condition due to the simultaneous imbalance of Water, Fire and Wind Elements which may also involve a toxic fever) an excess of Water Dhatu (possibly plasma or lymph fluids,) and “Wind” in the stomach. Other benefits described in the old texts include; increased longevity and opening all of the “Sen” (There are various types of “Sen” or channels in Traditional Thai Medicine. There are Gross Earth Physical “Sen” such as Blood Vessels. There are also more Subtle “Sen” such as channels of Bioenergy flow within the Subtle Body, known as “Nadis” in Sanskrit. In addition, there are also “Sen” as channels of the Mind.)

In recent years, the Thai Ministry of Public Health has published several books on Reusi Dat Ton. According these modern texts, some of the benefits of Reusi Dat Ton practice include; improved agility and muscle coordination, increased joint mobility, greater range of motion, better circulation, improved respiration improved digestion, assimilation and elimination, detoxification, stronger immunity, reduced stress and anxiety, greater relaxation, improved concentration and meditation, oxygen therapy to the cells, pain relief, slowing of degenerative disease and greater longevity. (Subcharoen, 5-7)

A recent study at Naresuan University in Phitsanulok, Thailand, found that after one month of regular Reusi Dat Ton practice there was an improvement in anaerobic exercise performance in sedentary females. (Weerapong et al, 205)

Thai Reusi Dat Ton and Indian Hatha Yoga

A survey of the traditional Indian Hatha Yoga text Jogapradipaka of Jayatarama from 1737AD identified the following 45 Indian asanas as having similar or identical counterparts in Thai Reusi Dat Ton; Svastikasana, Padmasana, Netiasana, Udaraasana, Purvasana, Pascimatanasana, Suryasana, Gorakhajaliasana, Anasuyasana, Machendrasana, Mahamudrasana, Jonimudrasana, Sivasana, Makadasana, Bhadragorakhasana, Cakriasana, Atamaramasana, Gohiasana, Bhindokasana, Andhasana, Vijogasana, Jonisana, Bhagasana, Rudrasana, Machindrasana (2nd variety), Vyasaasana, Dattadigambarasana, Carapatacaukasana, Gvalipauasana, Gopicandasana, Bharathariasana, Anjanasana, Savitriasana, Garudasana, Sukadevasana, Naradasana, Narasimghasana, Kapilasana, Yatiasana, Vrhaspatiasana, Parvatiasana, Siddhaharataliasana, Anilasana, Parasaramasana and Siddhasana. To date over 200 different Indian Hatha Yoga techniques have been identified which have similar or identical counterparts in Thai Reusi Dat Ton.

One unique feature of Reusi Dat Ton is the absence of Viparitakarani (Inversions) such as Shirshasana (Headstand), Sarvangasana (Shoulderstand.) Reusi Dat Ton also has no equivalents to Mayurasana (Peacock) or Bakasana (Crow). In Hatha Yoga both men and women use the left heel to press the perineum in Siddhasana (Adepts Pose), while in Reusi Dat Ton, men use the

right heel and women use the left. Reusi Dat Ton includes a series of “Joint Mobilization” exercises, many of which are very similar or identical to the Pawanmuktasana (Joint Loosening and Energy Freeing Exercises) taught by the Bihar School of Yoga in Northeast India. (Saraswati) Reusi Dat Ton also includes a system of self-massage, which is typically done prior to the exercises.

Both Hatha Yoga and Reusi Dat Ton practice forms of Surya and Chandra Bhedana Pranayama (Solar and Lunar Breathing.) However in Hatha Yoga men and women both use the right hand when practicing Pranayama (Breathing Exercises), while in Reusi Dat Ton men use the right hand and women use the left. Both use Ashwini Mudra (Anal Lock) and Jivha Bandha (Tongue Lock.) However, Reusi Dat Ton has no counterparts to Uddiyana Bandha (Abdominal Lock) or Jalandhara Bandha (Throat Lock.)

In Traditional Indian Hatha Yoga one will generally maintain an Asana for a few minutes. In contrast, Reusi Dat Ton tends to be more dynamic. Generally, one will inhale while going into the pose, hold the pose for several breaths, and then exhale when coming out of the pose. This is done to encourage the strong, healthy flow of Prana thru the Nadis (or Loam thru the Sen in Thai)

Reusi Dat Ton Today

Today in Thailand, Reusi Dat Ton is being used in various ways. Some practice Reusi Dat Ton poses and exercises as a way to improve and maintain overall health, in much the same way as Hatha Yoga and Chi Gong are used today. Others such as Ajan Pisit Benjamongkonware of Pisit’s Massage School in Bangkok used Reusi Dat Ton in combination with traditional Thai Massage techniques as a system of therapy. They will use specific techniques for specific ailments, rather like an ancient system of rehabilitation similar to modern day Chiropractic and Physical Therapy. Others consider the energetic effects with the aim of facilitating the normal healthy flow of bioenergy through the “Sen” or energy channels of the subtle body. There are also a few remaining Reusis who still use Reusi Dat Ton in the traditional way as part of their personal meditation and spiritual practice.