When I was pregnant with my son in Thailand, the subject of heat, high heat, came up often. Hot season is a lucky time to have a baby, I was told. No worries keeping your little one warm. I found this perplexing. I am from central Maine. All of my baby pictures are taken in snow banks (the light is better there!). In Thai summer with days in the upper 90’s fahrenheit, I was worried about how to keep the little bean cool.

When I arrived in the hospital to give birth, heat (or a lack of cold) came up

again. When my mouth got dry during delivery, I asked for ice chips. I am sure I got that out of a movie, or something. Dr. Udom, my fabulous obstetrician, and the attending nurses (all dressed in Pepto-Bismol pink) looked at me quizzically. I repeated it in Thai language. Still not getting through, I dropped it, having other fish to fry at that moment.

Some time later a cup of room temperature water appeared. That will do just fine, I thought.

After he was born, we settled into our room to rest (and watch the World Cup on TV!). Not much of a soccer fan, I relaxed and waiting patiently for ice packs. Clearly, I had not fully converted to the theory of heat. I would never have guessed that I would want to ice …, but I really, really did. Ice packs didn’t come. I inquired after some. The very kindly nurse looked at me quizzically, and then advised warm water.

I made do with warm water.

Before we left the hospital the next morning, having had two beautiful Thai meals and plenty of visitors, Dr. Udom came to our room. His advice? Rest. No cold foods and no cold drinks for a month. No cold water in the shower (which in Thailand is worth specifying). And come back for a check in ten days.

At home with our newborn, my ex-husband and sister-in-law knew exactly how to care for me. We would use heat. My ex-husband recently explained it to me this way. In the past after giving birth, a Thai mother would sleep in a small tent with a fire in order to sweat. The heat and the sweat would clear the unneeded fluid of pregnancy from her body, release toxins and kill bacteria. He described it as purifying, like a Thai sauna.

The Thai family into which I married has a long tradition of practicing Thai medicine. My ex-husband’s grandmother, Khun Yai delivered scores of babies as the only mid-wife and massage therapist in their village, a

settlement which sprang up in the dust of a ruby strip mine, where even children worked sifting the dirt for gems. The rubies are long gone and with them the jobs. The village is now mostly old women, their children and grandchildren moved away to Bangkok.

This photo of Khun Yai was taken in her last year. She was 81. Though her health was declining, it was a year of great joy. Her second grandson ordained as a monk, and her first grandchild was born.

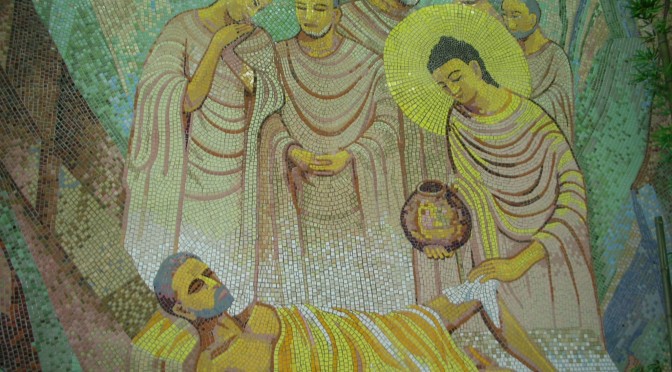

The family remember Khun Yai packing a small sack and walking to the house of women in late pregnancy to prepare for birth. She lived with mother and child until they were ready to get on without her. She prepared food to support birth and lactation. She collected and blended Thai herbs in teas and herbal baths, and she prepared a fire in a small tent where the new mother could rest and sweat, purifying her body after giving birth.

Khun Yai began to learn massage when she was only ten years old. Her own mother and grandmother had been mau nuat pan boran, roughly translated as doctors of ancient massage. I suspect her family, in the female line, have been practicing massage since the beginning of time. As a teenager, she trained in a local hospital in massage and midwifery, which was an honor for her family. Her grandchildren like to say that her father agreed to let her study, even though the hospital uniform skirt was a bit too short. In my mind’s eye, I see her in a simple skirt of early 1940’s vintage, while the women of her village wore ankle length sarongs.

Khun Yai was too feeble to make the trip to us, but she guided us through the weeks following my son’s birth. Dr. Udom respectfully recommended that Khun Yai would know exactly what we needed. In that way, I had the best of traditional Thai medicine in the care of a Western trained doctor.

As you might imagine, I did not sleep in a small tent by a fire in front of our

little urban house in Chiang Mai. Because we were in the city, my family used Thai herbs, in a tea and an herbal bath, to increase my internal heat and promote a gloriously detoxifying sweat. That combined with the high heat of Thai summer were incredibly healing for me.

When I returned to see Dr. Udom ten days after giving birth, I had lost all of the 25 pounds I gained in pregnancy. My son was nursing well. I was resting and well fed with food supporting milk production. I was sleepy as all get out, but well on the way to recovering, deeply grateful for the care of my Thai family.

More on the Thai herbs we used in my next post on Thai medicine for the New Mama!

Let me tell you a story. In May 2004, my brother had been in Iraq for just a couple of weeks serving in the Naval Reserves when I got a call from our dad. Yes, that kind of call. For the next few months, I did everything I could to be in hospitals in Bethesda, then Tampa to help him and my Rock-of-Gibraltar sister-in-law while he recovered from his wounds. This photograph was taken of Diana and Pete in Tampa during that first year of heavy lifting.

Let me tell you a story. In May 2004, my brother had been in Iraq for just a couple of weeks serving in the Naval Reserves when I got a call from our dad. Yes, that kind of call. For the next few months, I did everything I could to be in hospitals in Bethesda, then Tampa to help him and my Rock-of-Gibraltar sister-in-law while he recovered from his wounds. This photograph was taken of Diana and Pete in Tampa during that first year of heavy lifting.