I originally wrote this in response to a colleague who suggested that the Chinese term for ‘nerve’, 神經 [shénjīng], implied that the Chinese conceived of this concept as meaning: ‘links of transmission (經) of spirit (神)’. Over the years I have shared it with students and in some discussion groups as well. The feedback I received has encouraged me to correct, expand, and polish it. I also added some illustrations in this new version. I hope you will enjoy it.

I am greatly and gratefully indebted to Hugh Shapiro for his thorough research on this topic.

Introduction

Can we say that the nerves are ‘the links for the transmission of spirit within us’? Is that the way the Chinese saw it when they began to use the term 神經 [shénjīng] for ‘nerve’? When I heard that I had serious doubts, mostly because the Chinese already had an elaborate system of transportation in the body, consisting of channels, vessels, and a network of smaller conduits. I simply could not imagine that when descriptions of the nerve and the nervous system reached China, they thought: “Ah, that’s what was missing, that could be the vehicle for spirit transmission!”

I was prepared to give it the benefit of the doubt, though, and decided to see if there was any evidence for it. The combination of the two characters 神 and 經 by itself (be it very interesting) is not enough for me to believe that it became part of Chinese medical philosophy in the way that my colleague had put it.

I specialize in the Chinese-English terminology of Chinese medicine, a medicine that I have practised as well. Besides my studies in Chinese languages and cultures I have done studies in lexicology and terminology. A brief introduction to what terminology is and how it works in our field of knowledge can be found here.

Of importance for the following is: A term is only a term when it has a definition. A definition describes the concept that is conveyed by the term. When a term is translated into another language, the definition does not change. This principle is a prerequisite for adequate translation and communication in any specific subject field. There is nothing special about it; it is the way knowledge is communicated in this world. Nevertheless, it often is overlooked in one particular field of knowledge, namely Chinese medicine.

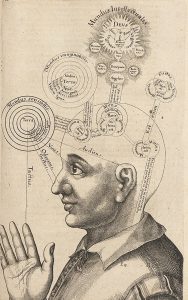

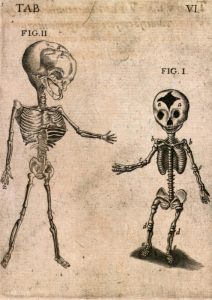

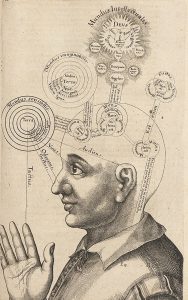

<Anatomiae amphitheatrvm, Robert Fludd, 1623>

So, it is the definition of ‘nerve’ that applies to 神經 and vice versa. There are many ways new terms are formed and for the Chinese terminologies of Chinese medicine and that of biomedicine (a.k.a. Western medicine) there are some specific problems. When the Chinese create new terms for concepts that they did not invent themselves, like ‘nerve’, what they are doing is trying to understand what the foreign term means (by investigating the definition of the concept) and then come up with a term for it in their own language.

If you translate that new word back into the foreign language without taking into account what definition is attached to it, you can come up with something different. And that is what happens when you translate 神經 as ‘spirit transmission’ or ‘lines for the transmission of spirit’, or ‘spirit channel’. Regardless of the problem that both characters have multiple meanings (an ignoramus could say that 神經 means ‘divine menstruation’), what you are doing when you follow this method, is giving a new and different definition to an existing term. And that makes communication in any discipline very difficult if not impossible.

The compound word 神經 [shénjīng] in the meaning ‘nerve’ is interesting because as a term it raises several questions. Imagine a doctor in China who comes into contact with Western anatomy for the first time in history. What would you say they will think? They see drawings of human bodies with lines, read the description of this new concept, and why o why don’t they come up with something like 腦經 ‘brain channel’, 腦氣經 ‘brain qì channel’ or another combination that fits what they read and see?

<De humani corporis fabrica, Andreas Vesalius, 1543, Basel>

As an aside:

The word 腦 [nǎo] in Chinese has the same definition as ‘brain’ – like many other anatomical words that were invented in different cultures without intercultural exchange. Think of ‘blood’, ‘heart’, ‘little toe’, ‘nose’, etcetera – all very straightforward terms, because they mean the same for everyone in all cultures and times.

Such questions occupied my brain when I was thinking about what my colleague brought forward, and they motivated me to search for references. And guess what? I found (at least part of) an answer to this intriguing issue that could make it even more intriguing. I have tried to summarize the story.

The history

The concept ‘nerve’ was first translated into Chinese by Johann Schreck (1576-1630), a member of the Society of Jesus who, before he sailed to China as a Jesuit missionary, had an impressive reputation in European courts as a gifted healer. Working with a Chinese scribe, he prepared a translation into Chinese of a Latin text in two parts, namely on anatomy & physiology and on perception, sensation, & movement (by Caspar Bauhin, first published in 1597 in Basel).

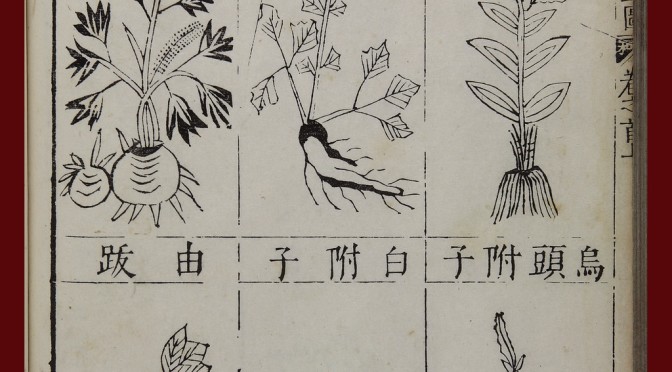

<Theatrum Anatomicum, C. Bauhin, 1605, Frankfurt>

After Schreck had served the Chinese rulers with his knowledge of astronomy (medicine and medical translation were private occupations) for a while he died, and Adam Schall (1592-1666), who had traveled on the same boat as Schreck, found a Chinese scholar, Bi Gongchen, whom Schall asked to translate the text into (more polished) literary Chinese. It was published in a single volume together with a text by Matteo Ricci, one year before the collapse of the Ming dynasty (1644).

In the text, entitled ‘Western Views of the Human Body, an Abbreviated Treatise’ (Taixi renshen shuogai ), ‘nerve’ is translated as 細筋 [xìjīn], which literally translates as ‘fine sinew’. The choice for 筋 ‘sinew’ reflects the understanding of nerves in Europe at that time. ‘Nerve’ and ‘sinew’ were, for instance, used interchangeably in early 17th century texts on anatomy. Also, the Latin ‘nervus’ means ‘bow-string, tendon, sinew’.

<Taixi renshen shuogai>

In Schreck’s text nervous function is explained by using the concept of 氣 qi circulation. The ‘fine sinews’ contain qi and no blood, and when they are cut, people lose their ability to move, etc.. The book did not give the Chinese much reason to become interested in an alternate method of healing, and the concept of nerves did not take hold in China until much later.

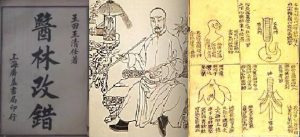

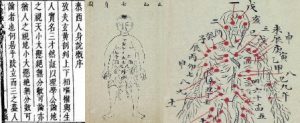

In Wang Qingren’s Yilin gaicuo (‘Corrections of Errors in the Forest of Medicine’), which after publication in 1830 became one of the most widely read medical texts in China (as it still is today), we find no mention of a term for ‘nerve’. Dr. Wang, however, recorded several anatomical notions that were revolutionary for Chinese medicine and in several ways heralded a period of modernization. For our story it is relevant that he presented anatomical ‘proof’ for what Li Shizhen had claimed in the Bencao gangmu, namely that the brain, and not the heart, was the mansion of the original spirit.

<Yilin gaicuo, Wang Qingren>

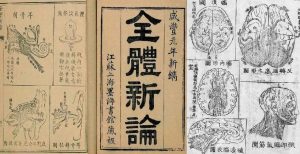

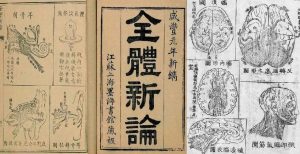

It was Benjamin Hobson (1816-1873), a medical missionary from England, who instigated renewed attention for the concept of nerve in China. With his text ‘A New Theory of the Body’ (Quanti xinlun, published in 1851) he had considerably more influence than Schreck. In the chapter on the brain and the nervous system, he introduced the term 腦氣筋 [nǎoqìjīn], which literally translates as ‘brain – qi – sinew’, that is, the sinew through which brain qi travels.

<Quanti xinlun>

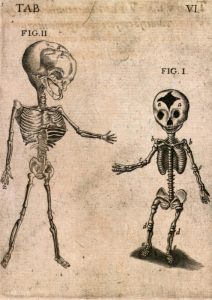

Although China was in the middle of a modernization movement, in the beginning of the 20th century, the concept of the nerve was still not easy for the Chinese to digest. Of the twelve different words that had been invented for ‘nerve’ since the beginning of the 17th century, five made it to the shortlist of a terminology committee meeting held in Shanghai in 1916. The purpose of that meeting was to standardize Chinese terms for numerous scientific concepts coming from the West and biomedicine was the most important subject. The term for ‘nerve’ was debated for over two hours before 腦經 ‘brain channel’ or ‘brain tract’ topped 神經 ‘spirit channel’ by eight votes to seven.

Why did it take 300 years for the concept of nerves to take hold in China?

1. It was not particularly relevant for Chinese medicine.

2. It was associated with the Western notion of ‘volition’. The Greek term for ‘motor nerves’ was, translated literally, ‘capable of choosing, purposive’. The action of nerves was inseparable from exercise of will. In the West, volitional action was a crucial defining feature of identity. For the Chinese, who did not hold such a view of identity, the idea of incorporating nerves into medical theory was not attractive.

<Theatrum Anatomicum>

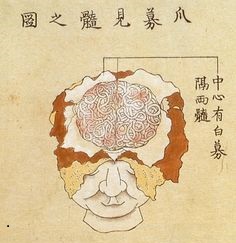

The term 神經 came to China via a different route. It was introduced in 1902 as a translation of the Japanese shinkei, which is written with the same characters. In 1774 it was coined by a Japanese doctor trained in Chinese medicine. He came up with the word after studying a post-Vesalian Dutch text on anatomy.

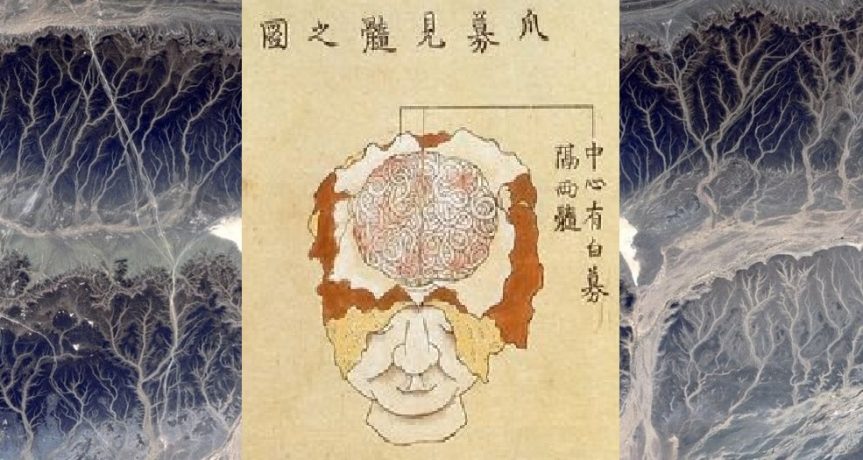

The story of the Japanese doctor resembles that of Wang Qingren. He went to an execution ground to observe the dissection of a cadaver in order to see whether the illustrations in the Dutch text made sense. When he was convinced that they did, he formed a translation group to study and translate the text, and that text is seen as the seed of biomedicine in Japan. He judged that the Dutch term zenuw (nerve) corresponded with keimyako – 經脈 [jīngmài], channels and vessels, and the term zenuw-vogt (nervous fluid), he argued, pointed to shinki – 神氣 [shénqì].

神氣 in Chinese medicine can mean several things: 1. spirit, vigor 2. In the Neijing, ‘spirit qì’ refers to the spirit, channel qì, right qì, the blood, and the yáng qì of the bowels and viscera. < Practical Dictionary of Chinese Medicine>. It is interesting to note that the Dutch word ‘zenuw’ (nerve) is directly related to the English word ‘sinew’.

Combining 神氣 and 經脈, our Japanese doctor-translator formed the neologism shinkei 神經 which consists of the first part of these two terms. Historians have not found evidence that the Chinese of the early 20th century were aware of the history of the term (namely that qì was part of its original full version), and argue that that is one of the reasons they favoured 腦經 [nǎojīng] as translation of ‘nerve’ in 1916.

Another note is that the word 神經 [shénjīng] already existed in classical Chinese as a designation for a genre of esoteric books. The Japanese shinkei 神經 is a new construction, derived from words unrelated to that classical meaning.

In the text mentioned below Hugh Shapiro asks the important question: Why then, did they eventually adopt the term 神經 [shénjīng] for ‘nerve’? According to Shapiro the reason can be found in the fact that thousands of Chinese trained in Japan and came back to China with Japan’s analysis of biomedicine in their luggage – accompanied by the terminology the Japanese used. Biomedicine (a.k.a. Western medicine) rapidly gained ground as part of the movement in China to modernize and catch up with the West. But more importantly, the Chinese were interested in the pathology of the nerves – a thing that was never described by the Jesuits who introduced the anatomy. And the Japanese doctors instructed the Chinese in nerve pathology as they had translated it from biomedicine.

<brain dissection, Japan, 18th century>

The concept of nerves as such did not appeal to the Chinese medical professionals (they didn’t really need it) but when they studied the illness neurasthenia as described by the biomedical literature of that time, they connected it to their understanding of depletion. In fact, neurasthenia, in Japanese shinkei shuijaku and Chinese 神經衰弱 [shénjīng shuāiruò], became much more important in China than in the countries where the idea originated but soon was discarded. Also, the foreign idea of ‘nervousness’ became very common in 20th century China.

Shapiro further argues that this can inform us that the Chinese and Western concepts of emotional and corporeal depletion were rather close, and that this is often overlooked when the differences between the two medical systems are discussed.

I might add that the ideas about several pathologies as described by Wang Qingren in connection to his, for China, rather new and revolutionary ideas about the brain and other anatomical parts, have contributed to the development of a more open view in Chinese medicine towards ‘facts’ instead of rigidly adhering to ‘theories’ only.

<Utriusque Cosmi …, Robert Fludd, early 17th century>

Literature

– Hugh Shapiro’s contribution in: ‘Medicine Across Cultures: History and Practice of Medicine in Non-Western Cultures’, a collection of essays edited by Helaine Selin (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003)

– Bridie Andrews’ Introduction in Yi Lin Gai Cuo – Correcting the Errors in the Forest of Medicine, and the chapter ‘On Brain Marrow’ in that book (published by Blue Poppy Press, 2007)

see also:

– Marta Hanson’s keynote lecture: Jesuits and Medicine in the Kangxi Court (1662-1722).