The Mistranslation That Changed Chinese Medicine

If you’ve ever heard that Chinese medicine is based on the "Five Elements," you’ve witnessed a translation error that fundamentally misrepresents the basic theory of the tradition.

What happens when we use the same English term to translate ideas from different Asian medical traditions? Conflating concepts coming from different medical and cultural contexts can lead to confusion that severely compromises our understanding and appreciation of the differences between medical systems.

One pernicious example of this is how common it is even among seasoned Chinese medicine practitioners in the West to say that their theory is based on the “five elements.” This phrase is using a term from the European cultural context to fundamentally misrepresent the basic worldview of Chinese medicine.

Let’s pick this apart together in order to see why this mistranslation matters. . .

Our starting point is to understand that, in the ancient period, traditions of medicine originated in relative isolation from one another on opposite sides of the Eurasian landmass. Historical texts dating from the last few centuries BCE show us that the Chinese medical tradition that had taken form at one end and the Indo-European medical tradition at the other were based on fundamentally different ideas.

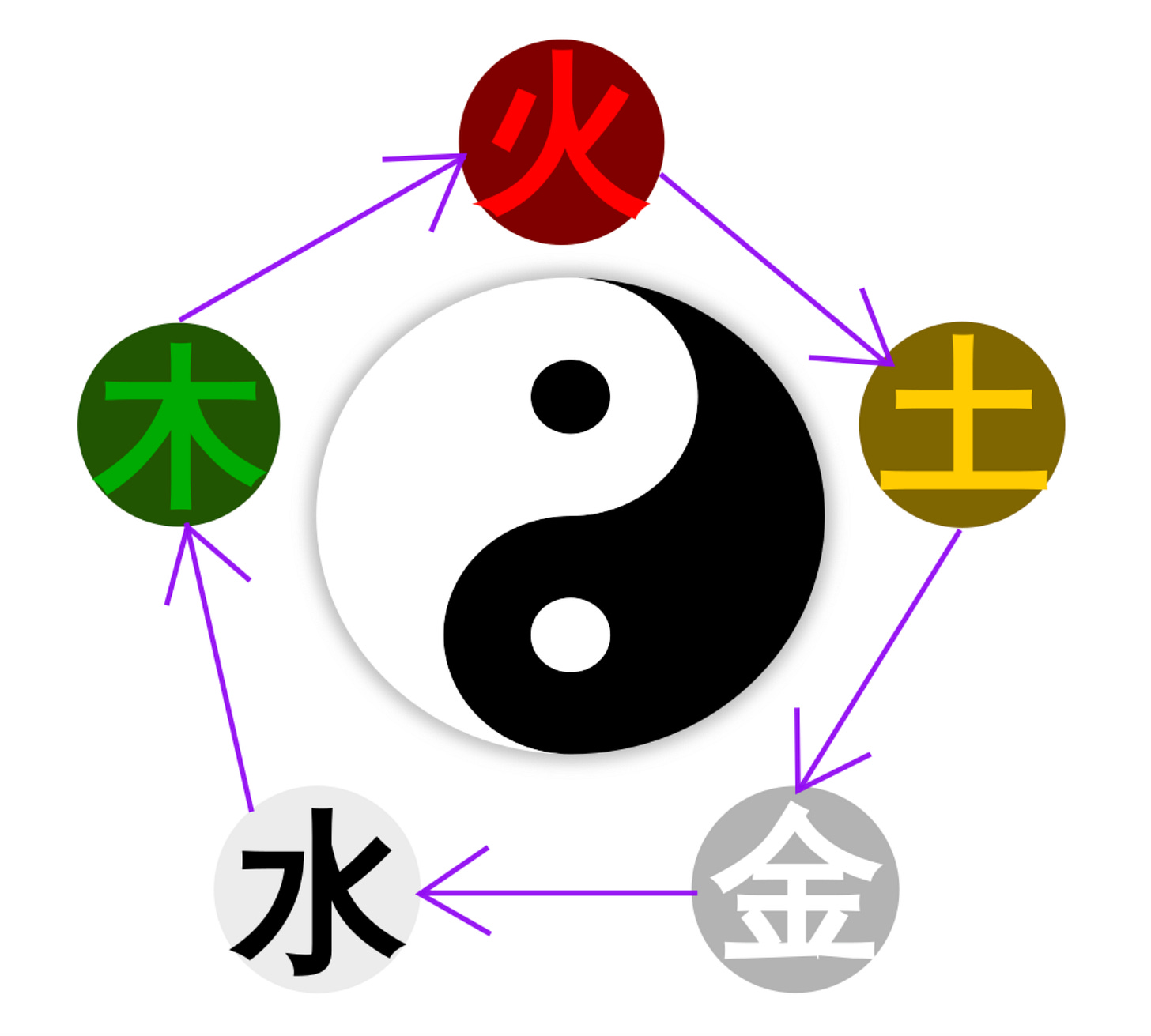

On the eastern side, foundational medical texts written in Chinese such as the Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi neijing 黃帝內經) talked about Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water being “five phases” (wuxing 五行). The key character 行 is based on a pictogram that originally depicted a crossroads or footsteps, and its core meaning is the noun “steps” or the verb “to walk.” It is associated with movement, directionality, and change over time.

On the other side of Eurasia, the Ancient Greek Hippocratic corpus that formed the basis of Greek and Roman medicine named Earth, Water, Air, and Fire the “four elements” (στοιχεῖα, stoicheia). Philosophers often added Void (αἰθήρ, aithḗr) to this list when signifying the absence of the other elements. There are also descriptions of these same elements (in India called mahābhūta) in Buddhist texts, such as the Great Elephant Footprint Simile (Maha-hatthipadopama-sutta), orally transmitted in the Pāli language since the last centuries BCE. They also appear in Sanskrit medical texts, such as the Āyurvedic classics Caraka’s Compendium and Śusruta’s Compendium (Caraka-saṃhitā and Śusruta-saṃhitā), that can be dated to roughly the same period. Whether these elements originated in India or Greece has been debated, but the fact that the elemental schema was shared between Europe and India is not disputed.1

In most schools of early Indo-European thought, the material elements of Earth, Water, Fire, and Wind are considered to be ontologically real substances that arise within the Void. They are the four fundamental building blocks of all material reality. This stands in marked contrast to Chinese cosmology, where everything that exists (i.e., the ”ten thousand things,” wanwu 萬物) are composed of the unitary substance of qi. In Chinese thought, the five phases thus are not separate ontologically existing things, but rather processes, patterns of change and transformation in how qi manifests in time.2

These philosophical and cosmological distinctions provide different starting points for East Asian and Indo-European forms of medicine. In Chinese medicine, where the human body, like all physical material, is composed of qi, the default state of the human being is one of wholeness, health, and harmony. It is only through error, or deviating from the Dao, that one deteriorates into sickness. Indo-European texts, in positing four primordial building blocks instead of one, present a less harmonious picture. The elements are not only distinct, they are often mutually incompatible, which is a persistent source of suffering for humans. Buddhist discourses on the body, for example, say that the relationship between the elements is like four venomous snakes trapped in the same basket. Their mutual antagonisms and perturbations cause disease, and inevitably in old age, they finally fall apart completely.3

If these differences between the Chinese phases and the Indo-European elements are so clear, then why do we find slippage between them today? Western-language translations equating phases and elements can be traced as far back as Matteo Ricci (1552-1610), the Jesuit envoy to the Chinese empire who first translated between European and Chinese philosophical and religious ideas. Ricci and other writers of his time were cognizant of the differences between elements and phases, defining the elements as “structural” (ti 體, yuan 源) and the phases as “processual” (yong 用, liu 流).4 Nevertheless, Ricci’s decision to translate the Greco-Roman elements as “the four phases” (sixing 四行) allowed later practitioners to elide these important distinctions and make simplistic equations between elements and phases.

Fast forward to the 1970s, when a modern style of practice called “Five Element Acupuncture” became central to the popularization of Chinese medicine in the English-speaking world. This system was primarily developed and promoted by the British physiotherapist and acupuncturist J.R. Worsley (1923–2003), and many acupuncture practitioners active in Europe and North America today trace their lineage to him.

Ricci’s and Worsley’s equation of phases and elements promoted the widespread misunderstanding that the wuxing can be thought of as ontologically existent “things,” but they are not. The phases should be understood as qualities rather than essences. They are adverbs or adjectives rather than nouns. Rather than thinking in terms of Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water per se, we should think in terms of Wood-like, Fire-like, Earth-like, Metal-like, or Water-like qi. The noun is always qi because in Chinese thought that’s the only substance there ever is.

Clarifying these concepts has clinical implications, but is also important because of how metaphors structure our experience of ourselves and the world we inhabit.5 It’s one thing to live in a fractured body in a universe where competing substances vie for primacy. It quite another to be embedded in a unified whole where body and cosmos are composed of the same primordial stuff. It’s one thing for one’s idea of health and illness to be organized around the inevitability of disintegration, and quite another for it to be based on an assumption of harmonious oneness.

The stakes of this mistranslation extend far beyond academic pedantry. When we impose the language of “elements” onto Chinese medical concepts, we inadvertently import a Western metaphysical framework that is fundamentally at odds with the Chinese worldview. We lose sight of the dynamic, processual nature of the phases and replace it with an ontology that belongs to a different tradition entirely. Better historical understanding helps us to resist the temptation of false equivalences and to preserve the conceptual integrity of the traditions we study.

1 Filliozat, J. (1964). The Classical Doctrine of Indian Medicine: Its Origins and Its Greek Parallels. Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal; McEvilley, T. (2002). The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies. New York: Allworth Press, 300–309.

2 Jones, CB. (2016). Creation and Causality in Chinese-Jesuit Polemical Literature. Philosophy East and West 66(4), 1251-1272. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pew.2016.0090.

3 Salguero, CP. (2018). “This Fathom-Long Body”: Bodily Materiality & Ascetic Ideology in Medieval Chinese Buddhist Scriptures, Bulletin of the History of Medicine 92.2: 237–60. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/1/article/698172.

4 Hsu KT. (1997). “The Transmission of Western Four Elements Theory in Late Ming China.” Tsing Hua Journal of Chinese Studies n.s. 27.3: 347-380. https://thjcs.site.nthu.edu.tw/p/406-1452-41461,r2974.php

5 Lakoff, G, and M Johnson. (2003 [1980]). Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

The translation of "wuxing" as "five elements" is certainly contentious. And I think we can all agree on the difficulty in giving a single-word translation for the multivalence of Chinese words. That being said, Worsley is clear that his use of "element" is not to be taken in the ontological sense of Greco-Roman "things". In the following passage, he defends his use of "element" on temporal grounds:

"The term element, in the context of 'the Five Elements', describes a stage in the ceaseless flow of energy in Nature and in the person. The Chinese word is sometimes translated as 'phases' to avoid any suggestion that the elements are like the ultimate building blocks of all matter, a concept that arises much later in Greek and Roman philosophy. This does not do justice to the idea, however, that an element is vital and alive at all times, not just in its 'own time'. The elements do indeed describe the way in which the different facets of the whole come to the fore in their natural rhythms, both annual and daily. The Fire element, for example, represents the phase or the cycle where things and people are in their summer stage of warmth, fullness and maturity. By association this is extended to include many of the mental, emotional, and spiritual qualities of a similar type. In contrast, the Water element represents the winter stage where growth has ceased and activity is under the ground and characterised by determination, resolve, and a will to survive until the spring. The elements together represent a whole cycle of birth, growth, decay and death, and rebirth; but the faculties and attributes which they control and create are with us all of the time and allow us to meet the changing circumstances of our lives appropriately". (Worsley, Traditional Diagnosis, 215).

I think this is a reasonably nuanced position, though we still face the issue of "element" having ontological connotations in English. To resolve this, some practitioners use the hybridized phrasing "phase-element". My own view is that language gives us the advantage of articulation but also the disadvantage of being a construction of signifiers, where the most we can do is "point" to a notion. This is precisely why the Chinese relied on a pictographic form of writing.