Not Just a Cup of Tea: Ho Yan Hor and Chinese Herbal Tea Heritage in Malaysia

By Qiuyang Su, Danny Tze-ken Wong, Tan Miau Ing

In the state of Perak, Malaysia, communities predominantly of Hakka and Guangdongese descent who migrated from southern China since the late nineteenth century, constitute a significant portion of the population (Lin, Li, and Huang, 2024). The climate in Perak, similar to that of Guangdong, is characterized by hot and humid conditions. These environmental factors often lead to ailments associated with “dampness” and “heat” among the local population, making herbal remedies particularly relevant and well-suited to addressing these common health concerns.

In 1941, Ho Kai Cheong (何繼昌), a Guangdongese herbalist born in Malaya, established a modest tea stall in Ipoh, which eventually grew into Ho Yan Hor (何人可), today’s most iconic Chinese herbal tea brand in Malaysia. Rooted in a multi-ethnic community and shaped by an industry-driven economic context, the brand has evolved over 84 years from a local enterprise into a heritage icon and a leading pharmaceutical company with a global presence (Ho Yan Hor Museum, 2025). Despite the long-standing presence of Chinese herbal tea in Malaysia, research on its cultural heritage and social impact remains limited.

Tin and Tea: Creating Wealth and Health in Perak

Located on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula in Malaysia, Perak’s prominence began with the discovery of tin in Larut in 1848. This discovery catalyzed rapid development as mining activities proliferated throughout the 19th century, attracting significant Chinese immigration (Khoo and Abdur-Razzaq 2005, 15–20). Under colonial administration, Perak emerged as a leading tin producer, contributing over half of Malaya’s tin output and accounting for a quarter of global production. Tin mining brought significant prosperity and population growth to the region. In addition to tin, rubber played a crucial role in shaping Perak’s economy and attracting a large influx of laborers. By 1947, the Chinese diaspora in Perak had reached 444,509, constituting 46.6% of the state’s total population and surpassing both the Malay and Indian populations (Economic History n.d.). The Chinese maintained a high percentage among the ethnic groups for the following decades.

The 19th century witnessed the concurrent development of traditional and colonial healthcare systems in Malaya. Indigenous and folk medicine practices were prevalent throughout the peninsula. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has long been an integral part of local community in Malay Peninsula. In 1879, Eu Kong, a native of Guangdong, established the first Chinese herbal medicine shop, Yan Sang, in Gopeng, Perak. It subsequently evolved into Yu Yan Sang (餘仁生), a highly esteemed listed company specializing in the production and sale of traditional Chinese herbs and medicines (Yeung 2004, 138). The practice of traditional Chinese medicine continued to grow, and in 1925, the Perak Chinese Herbal Medicinal Hall was established in Ipoh, further advancing its accessibility and influence in the region (Wong et al. 2019).

During World War II, Malaya, which included the state of Perak, underwent significant economic, social, and political transformations. The conflict resulted in widespread poverty, scarcity of resources, and severe health issues, burdening the population’s access to healthcare services. Government records show that public health deteriorated seriously in 1940s. Malaria was the great killer, although dysentery and malnutrition probably contributed to a significant portion of the mortality (Annual Report 1947, 68). After the war, the Perak Chinese Physicians Association and the Perak Chinese Physicians and Druggists Association were established, reflecting the growing demand for traditional Chinese medicine (Wong et al. 2019). In 1947, the Perak Choong Wah Hospital (霹靂中華醫院) was established by the Association to provide charitable, non-profit healthcare for the underprivileged (Perak Choong Wah Clinic 2025).

Chinese herbal tea, a folk healing tradition also known as “cooling teas,” was introduced to British Malaya alongside the introduction of Chinese medicine. Typically, a Chinese physician prescribes a remedy in the form of a formula consisting of multiple components. These formulas are usually boiled for a specified duration to produce a medicinal liquid known as a tang (湯), or decoction. In contrast, Chinese herbal tea uses much simpler formulas with only a few ingredients, which are typically local and readily available plants (Zong and Liscum 1996, 2). Chinese herbal tea has been popular in Southern China for centuries and are celebrated for their distinctive abilities to clear heat and detoxify. These teas come in a variety of formulations, each containing a broad spectrum of bioactive compounds (Liu et al. 2024). It is tailored to address common ailments such as dyspnea, rapid breathing, cough, or phlegm-related conditions. In early 20th century, Chinese herbal tea shops were promoted in Southeast Asia and other countries. Among these, the most renowned was Wong Lo Kat herbal tea (Guo 2024).

The Legacy of Ho Yan Hor

The history of Ho Yan Hor herbal tea traces back to the 1940s, originating on Treacher Street in Ipoh, Perak. Ho Kai Cheong, the founder of Ho Yan Hor, was born in 1910 in Kati, Perak. His parents, who hailed from Panyu, Guangdong, operated a dim sum café in Kuala Kangsar. Ho was sent to his ancestral hometown, Panyu, in 1918 to further his education, returning to Malaya in 1924 (Ho Yan Hor Museum 2025). His early exposure to traditional learning and subsequent experience working at a Chinese medical hall nurtured his lifelong interest in Chinese medicine. Inspired by his passion for Chinese Medicine, Ho pursued further studies at the Ganton Wah Lam National Physician’s School in Hong Kong, from which he graduated in 1940, obtaining professional training in Chinese medicine (Fig. 1).

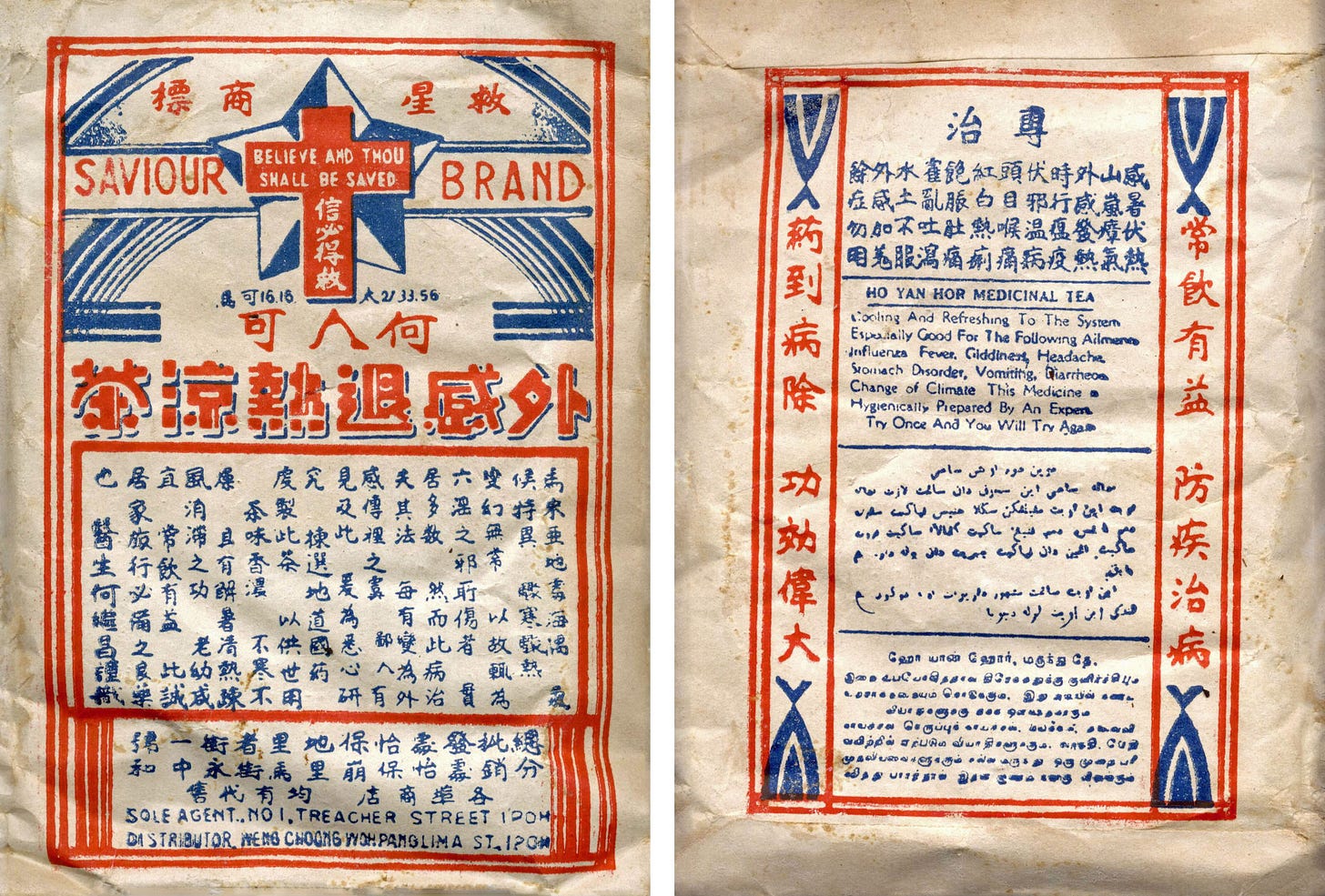

Ho began his career as a Chinese physician in 1941, but ceased due to the Japanese occupation. Following the war, miners in Perak began rehabilitating their mines and sought workers to resume operations. Ho Kai Cheong realized that many Chinese colliers suffered from colds, runny noses, and fevers due to body heat. This rekindled his passion for Chinese medicine, and he developed a flu remedy based on a carefully formulated blend of Chinese herbs, including those for dispelling body heat and Eight Formula sugar cane extract, which helps to dispel exogenous influences.

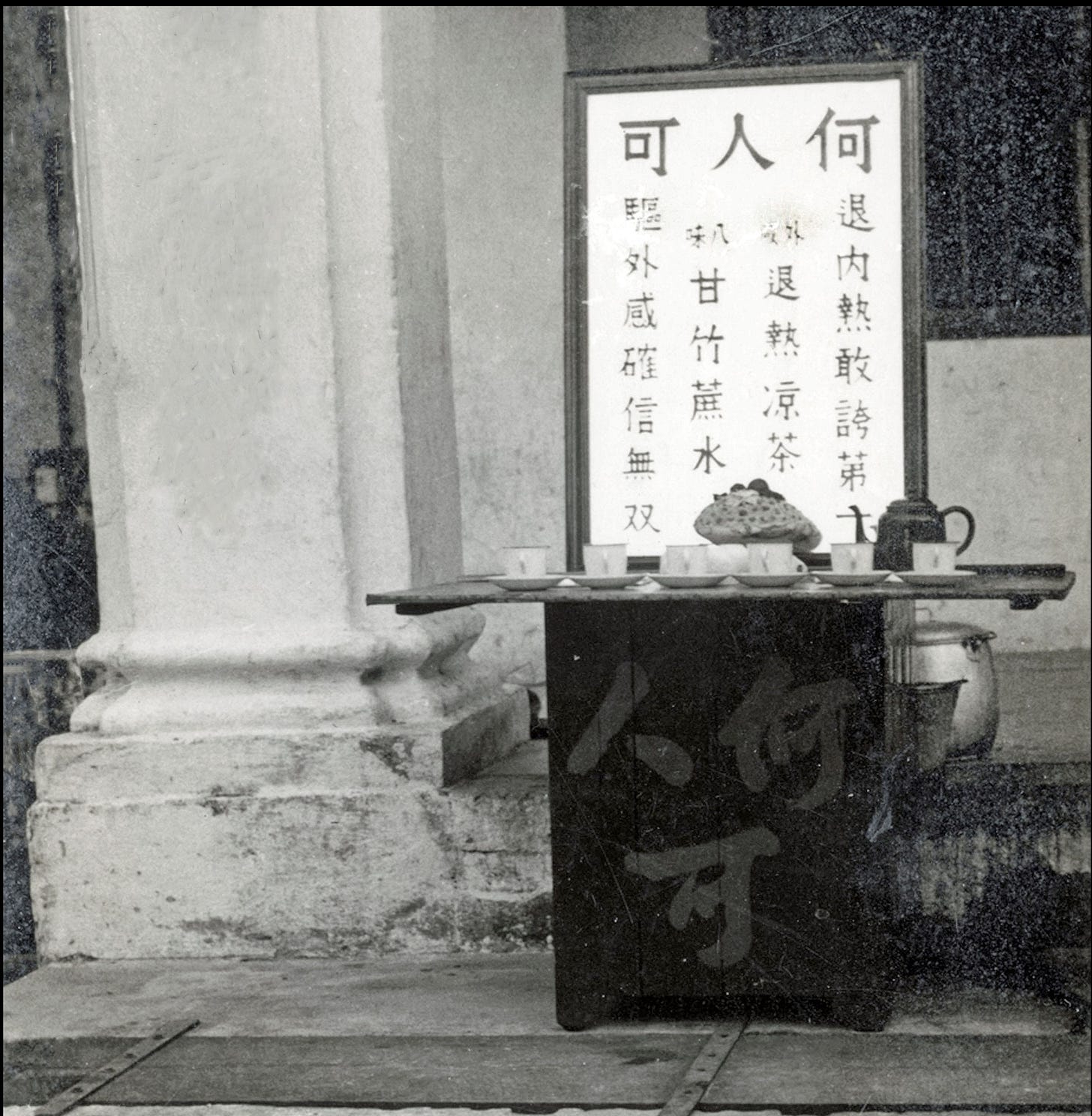

With an initial modest capital of $4, Ho Kai Cheong established his first tea stall on Teacher Street, offering the herbal remedy as a natural solution to alleviate these conditions (Fig. 2). Timing his sales to coincide with the return of coolies and workers in the afternoon and into the night, he was surprised when the herbal tea sold out at 5 cents a glass within less than an hour. His tea went on to eventually gain widespread popularity in the community.

Typically, Chinese herbal preparations involve processing dried herbs into powdered, coarsely ground, sliced, or fragmented forms, while fresh herbs are sliced or torn to maximize their surface area (Wu et al. 2018). In 1947, Ho Kai Cheong introduced an innovative concept: packaging Ho Yan Hor Herbal Tea for sale in coffee shops and Chinese medical halls (Fig. 3). Priced at ten cents per pack, the tea became a popular remedy among the local residents. Ho soon became known publicly as the “King of Herbal Tea.”

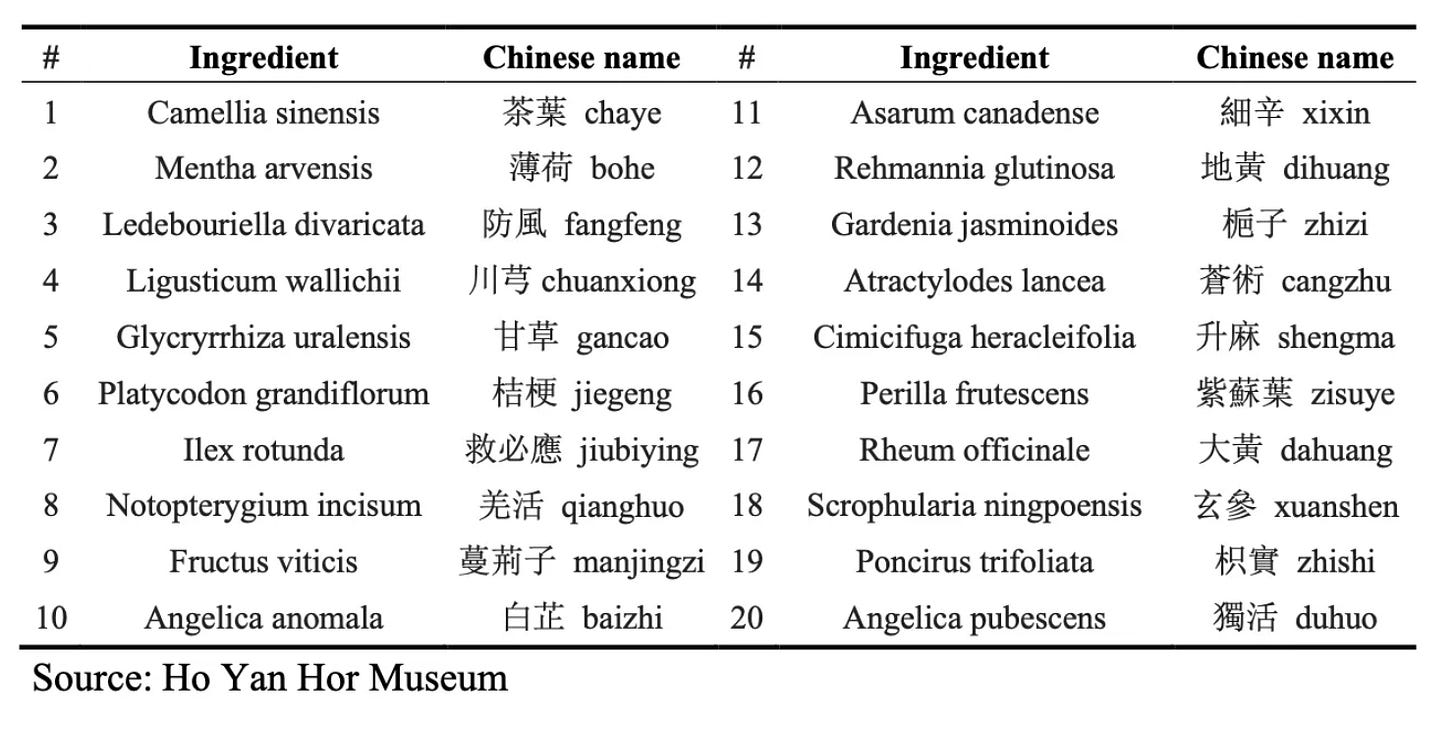

As indicated in Table 1, Ho Yan Hor herbal tea is formulated with a combination of various herbs traditionally used in Chinese medicine. Unlike common herbal cooling teas in Guangdong, such as Wong Lo Kat and the popular “Twenty-Four Flavors,” which mainly include herbs like chrysanthemum, honeysuckle, prunella vulgaris, and licorice, the Ho Yan Hor formula features a broader array of potent medicinal ingredients (Guo 2024). The formula incorporates potent heat-clearing and detoxifying agents, such as scrophularia, gardenia, and rhubarb, as well as herbs that dispel wind and dampness to alleviate symptoms of external colds and body aches. Additionally, it contains ingredients like atractylodes lancea, which dries dampness and supports the spleen, and licorice root to harmonize the potent medicinal properties. This creates a balanced remedy that maintains wellness by addressing both acute external symptoms and chronic internal imbalances. In times when aspirin and antibiotics were not readily available, it served as a highly effective treatment for such ailments (Ho 2009, 691).

Table 1. Ho Yan You Herbal Tea Formula in the 1940s.

Commercialization and Globalization

Building on the success of Ho Yan Hor herbal tea, the Ho Yan Hor Medical Hall was officially established in 1948. Several signature Chinese medicine products had been developed, including Ho Yan Hor Oil (何人可油), Ching Tim Kam Jik San (清甜疳積散), and Ko Kou Tan (可口丹). The continual growth reflected the local demand for traditional remedies.

In 1957, the Asian Flu spread rapidly across the globe (Honigsbaum 2020). During this time, Ho Yan Hor herbal tea gained popularity as an alternative remedy to Western medicine, valued for its perceived effectiveness in relieving symptoms such as fever and dizziness, promoting self-healing, and providing accessible household relief from influenza. The Ho Yan Hor factory, established in 1954, employed workers in the manufacturing process, marking the beginning of its modern commercialization. Recognizing the importance of marketing, Ho utilized innovative strategies, such as equipping his distribution vehicle (a Fordson van) with loudspeakers to advertise the benefits of his products across neighborhoods.

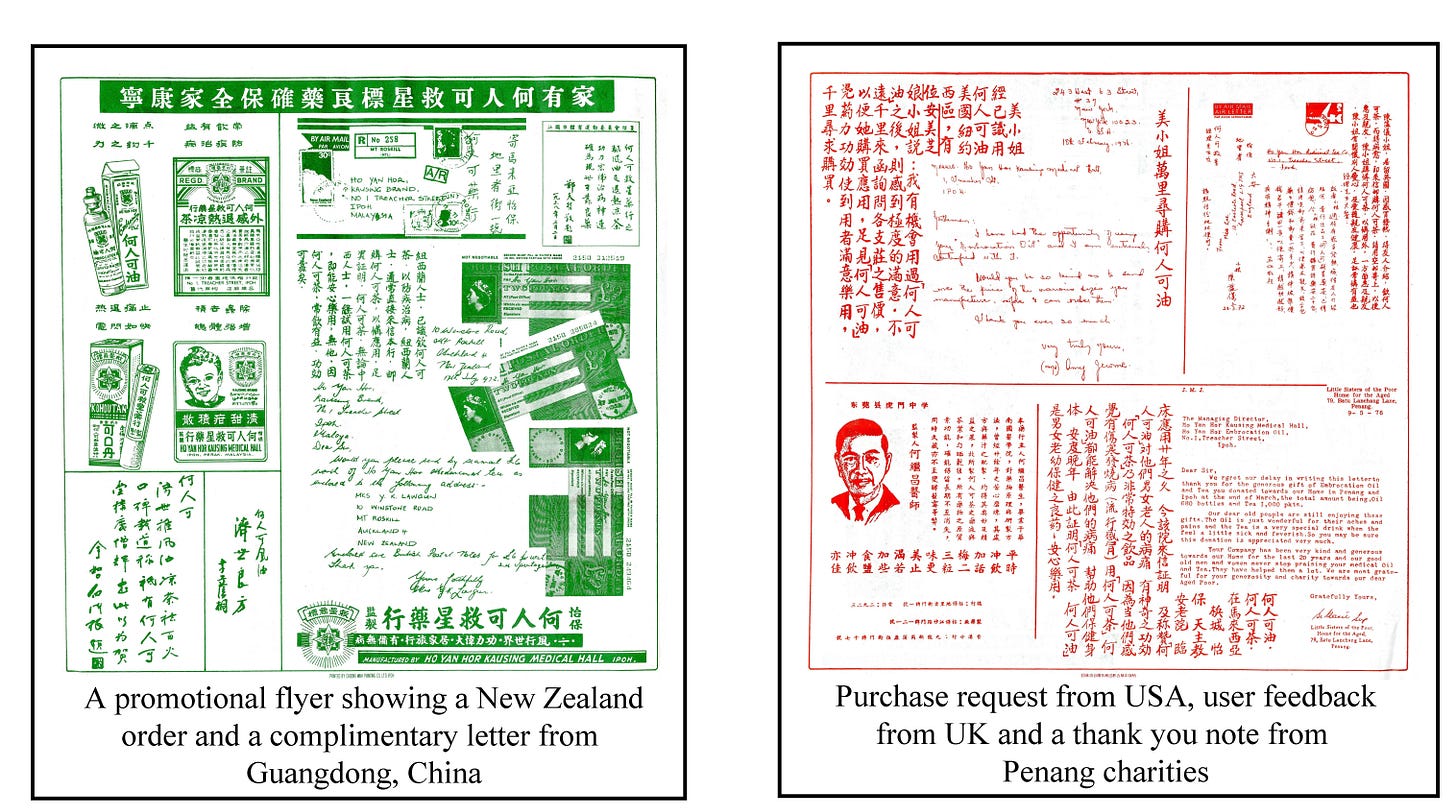

In the 1960s, Ipoh was home to numerous herbal tea vendors, many of whom hired young women known as “herbal tea ladies” (leong char mooi) to attract customers. Large Ho Yan Hor tea stalls also sprouted across the country. Leveraging his strong connections with Hong Kong, Ho Kai Cheong capitalized on the widespread popularity of Guangdongese opera and Hong Kong cinema among Chinese communities in the 1950s and 1960s. Famous performers from Hong Kong, including actress Tang Pik Wan (鄧碧雲) and TVB actor Cheng Gwan-Yin (鄭君綿), were invited to visit Ipoh for promotional events. Ho Yan Hor has consistently produced a series of advertisements in major newspapers across the country, with small-sized ads that consistently convey a continuous message to reinforce consumers’ brand recognition (Vijayan 2022). It registered its trademark and officially established its first overseas brand in 1960. By the 1970s, the brand had expanded its sales to include other countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and New Zealand (Fig. 4).

Since the 1980s, the depletion of Perak’s tin reserves and the global downturn in natural rubber demand have ushered in a period of economic transition. In response, the state government pursued diversification by promoting manufacturing as a new growth engine, supported by expanded infrastructure and industrial development. Industrial estates were progressively established across Perak (Perak Investment Management Centre 2025). Ho Yan Hor has responded by introducing new herbal varieties tailored to specific health needs, modernizing packaging, and rebranding to attract younger consumers while maintaining its heritage.

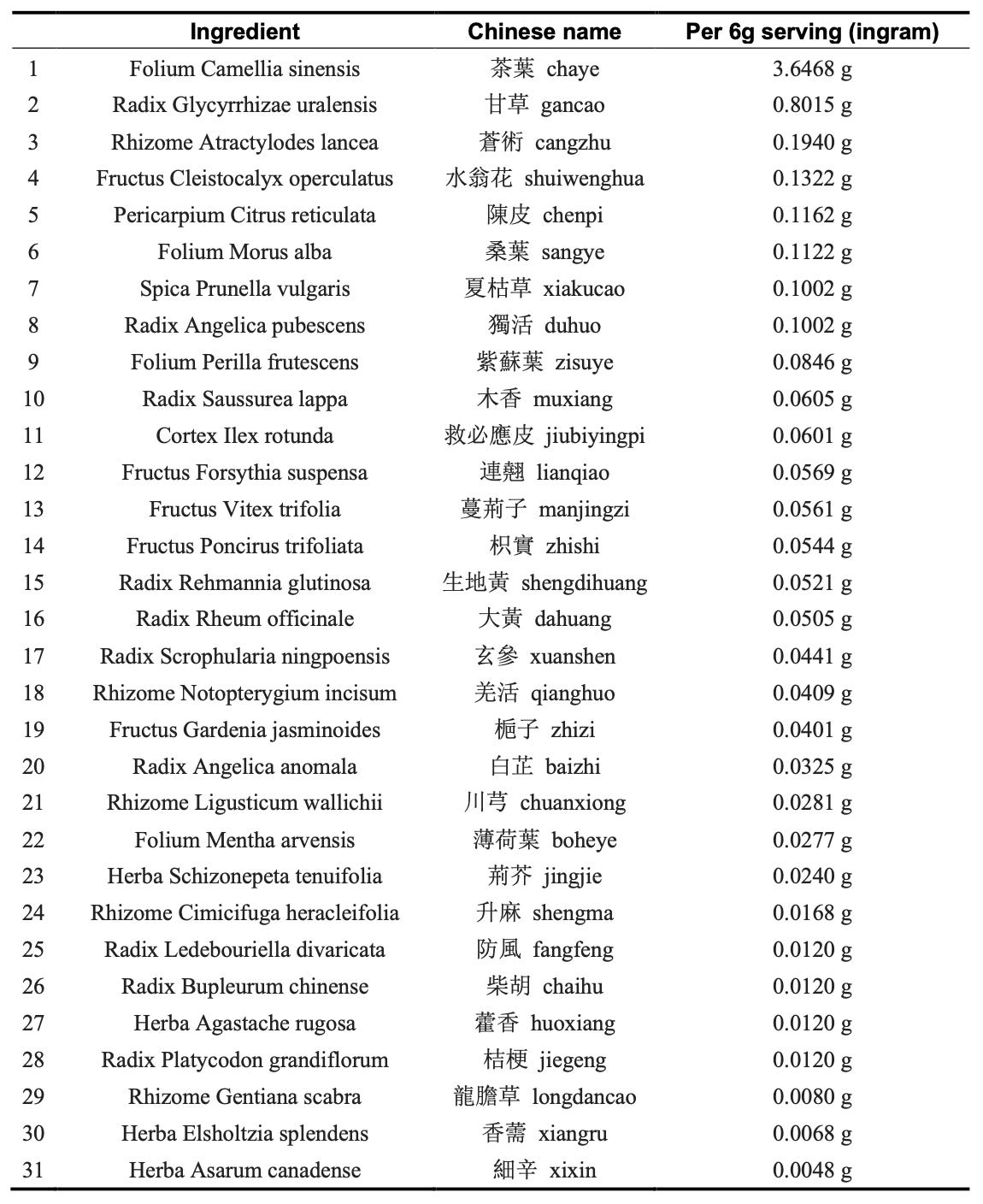

The original recipe has since undergone systematic refinement and expansion to include 31 herbs to maximize the therapeutic value and health benefits of the herbal tea (Table 2). The new formula is crafted to clear heat, dispel dampness, regulate qi, and alleviate pain. It is conveniently packaged in aluminum cans. Additionally, the introduction of these new products and packaging has reinforced the brand’s message of promoting herbal wellness among all Malaysians.

Table 2. Ho Yan Hor Herbal Tea New Formula

The Malaysian herbal tea market has experienced significant growth in recent years, fueled by consumers’ increasing preference for natural, health-promoting alternatives to caffeinated drinks. The market showcases innovations in herbal blends, sustainable packaging, and convenient wellness products (Mobility Foresights 2025). Amidst growing competition and changing consumer lifestyles, Ho Yan Hor has adapted by introducing functional teas such as Gold Tea, Night Tea, and the Everyday Series, thereby maintaining its position as Malaysia’s leading brand with the most diverse range of herbal teas, the evolution of its manufacturing and packaging not only demonstrates the brand’s progression through different historical stages but also reflects Malaysia’s broader industrialization and shifting consumer market trends.

Cultural Heritage and Medical Transition

Malaysia, with its rich biodiversity and multicultural traditions, fosters the development of a dynamic Chinese herbal tea and medicine sector. Remedies based on local flora are still prevalent in households and present significant potential for the creation of new herbal products. After the war, Perak experienced significant political and economic transformations that facilitated modernization and rapid development. The ascent of Ho Yan Hor, established in Perak during the 1940s and later expanding nationwide, coincided with these broader economic and industrial changes. The increasing popularity mirrored robust local demand for healthcare and the adaptation of traditional remedies to evolving social contexts. Despite the creation of Western health institutions, traditional medical practitioners maintained a dominant role within local communities (Mohd Sukri 2020). By 2024, the number of Chinese medicine practitioners had continued to grow, with 402 Chinese medicine halls and 482 registered physicians, though the actual figures are likely even higher (FCPMDAM, 2016).

Herbal tea remains highly popular in Malaysia, reflecting both enduring cultural traditions and increasing health awareness among consumers. Market analyses project that Malaysia’s herbal tea industry will expand from USD 1.2 billion in 2025 to USD 2.7 billion by 2031, registering a compound annual growth rate of 14.3% (Mobility Foresights 2025). Rich in bioactive compounds, herbal teas possess antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and hepatoprotective properties, and are traditionally valued for their ability to clear heat, reduce fever, soothe the throat, and relieve coughs (Lin, Li, and Huang, 2024).

Notably, significant ethnic differences exist in the knowledge and consumption of Chinese herbal tea across Malaysia. A survey in Kedah, northern Malaysia, found that many Chinese consumers maintain this practice as a cultural tradition, motivated by its perceived safety and health benefits (Teh, Jaafar, and Asma 2020). Over the past century, herbal tea has become not only a cultural emblem but also a prosperous business sector. Chinese entrepreneurship has been pivotal in shaping Malaysia’s societal and economic development. Perak has rapidly evolved from its traditional economic foundation of tin mining and related industries to a diversified array of manufacturing and service sectors, ranking as the seventh-largest by economic size and contributing 5.5% to the national GDP in 2020 (Zafri and Morhalim 2022). As of 2020, the Chinese community in Perak numbered 643,627, constituting 27.22% of the state’s population, with the highest concentration in Ipoh (Jiao and Singh 2024).

Since the 1980s, the narrative of Ho Yan Hor has embarked on a new chapter, characterized by a shift from traditional remedies to modern pharmaceutical manufacturing. Following the succession from Ho Kai Cheong to his son, David Ho, the family business evolved into a research-driven pharmaceutical enterprise. Upon his return in 1980, equipped with professional training in pharmacy, David Ho established Hovid Berhad, bringing innovation, scientific production, and modern management practices. By the 1990s, Ho Yan Hor had evolved from a traditional herbal brand into a GMP-certified and Halal-accredited pharmaceutical manufacturer with an expanding international presence. Importantly, while numerous traditional herbal products exist, few have successfully transitioned from folk remedies to high-value modern biomedical brands. Thus, the case of Ho Yan Hor and Hovid presents a particularly significant and insightful example of this evolution.

Conclusion

The historical trajectory of Ho Yan Hor embodies the post-war evolution of Chinese herbal tea cultural heritage in Malaysia within the socio-economic transformation of Perak. This traditional herbal beverage adapted to processes of industrialization and commercialization, reflecting the broader modernization of traditional Chinese medicine in the country. The sustained success of Ho Yan Hor demonstrates how traditional Chinese medical knowledge can be reinterpreted and institutionalized within modern pharmaceutical frameworks. By fusing heritage-based practices with Western scientific production, marketing strategies, and regulatory standards, the company has evolved from a local family enterprise into a modern pharmaceutical corporation of both national and global relevance, serving as a model of cultural continuity amid technological and economic change.

As one of Malaysia’s most prominent functional herbal teas, Ho Yan Hor’s legacy extends far beyond being “just a cup of tea”; it is a testament to the enduring value of Chinese herbal medicine and its seamless integration with modern consumption advancements. Its evolutionary journey reflects how traditional remedies can evolve through innovation while retaining their cultural essence. This synthesis not only strengthens the brand’s position in the industry but also serves as an inspiring model for the broader healthcare sector, offering insights into how traditional and modern medicine can work in harmony to meet evolving health needs.

Bibliography

Annual Report on the Malayan Union for 1946. 1947. Kuala Lumpur: Malayan Union Government Press.

Federation of Chinese Physician and Medicine Dealers Association of Malaysia (馬來西亞華人醫藥總會). 2016. The 60th Anniversary of FCPMDAM cum the 11th ASEAN Congress of Traditional Chinese Medicine[馬來西亞華人醫藥總會成立60周年紀念志慶暨第11屆亞細安中醫藥學術大會紀念特刊], 1955-2016. Kuala Lumpur: FCPMDAM.

Guo Wenna郭文鈉, 2024. “From Individual Life to Public Health: The ransformation of Lingnan Herbal Tea During the Late Qing and Republican Periods[從個體生活走向公共衛生領域:晚清民國時期嶺南涼茶的轉折].” Cultural Heritage, no. 5.

Ho Yan Hor Museum. 2025. “The Inspirational Journey of Dr. Ho Kai Cheong, the Visionary Herbalist with a Servant Heart.” https://hyhmuseum.com/ho-yan-hor-museum-03.Accessed June 20, 2025.

Ho, T. M. 2009. Ipoh: When Tin was King. Ipoh, Malaysia: Perak Academy.

Honigsbaum, Mark. 2020. “Revisiting the 1957 and 1968 Influenza Pandemics.” The Lancet 395, no. 10240: 1824–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31201-0.

Jiao, Y., and M. K. Mehar Singh. 2024. “Chinese in the Linguistic Landscape of Chinese Communities in Malaysia: A Tale of Three Cities.” International Journal of English Linguistics 14, no. 5.

Khoo, S. N., and L. Abdur-Razzaq. 2005. Kinta Valley: Pioneering Malaysia’s Modern Development. Ipoh: Perak Academy.

Lin Xingmei, Li Huiping, Huang Baokang. 2024. “Chemical constituents, health-promoting effects, potential risks and future prospective of Chinese herbal tea: A review.” Journal of Functional Foods 121 (October 1): 106438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2024.106438.

Liu Jingzhe劉兢哲, Zheng Chenhe鄭辰赫, Zeng Rudan曾茹丹 et al. 2024. “Research Progress on the ‘Fire Reducing’ Effect of Guangdongese Herbal Tea [廣式涼茶“瀉火”功效的研究進展].” Xian Dai Shi Pin, no. 12. https://doi.org/10.16736/j.cnki.cn41-1434/ts.2024.12.068.

Mobility Foresights. 2025. Malaysia Herbal Tea Market Size and Forecasts 2031. July 15. Accessed September 20, 2025. https://mobilityforesights.com/product/malaysia-herbal-tea-market.

Mohd Sukri, N. L. 2020. “British Colonialism: The Development of Health Institutions in Perak, 1911–1939.” In Innovation and Transformation in Humanities for a Sustainable Tomorrow, edited by N. Samat et al., vol. 89, 511–21. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences. European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.10.02.46.

Perak Choong Wah Clinic. 2025. “A Brief History of Perak Choong Wah Clinic(霹靂中華醫院史略).” Perak Choong Wah Clinic. Accessed February 20, 2025. https://www.perakchoongwahclinic.org.my.

Perak Investment Management Centre. 2025. “Overview: Perak.” Accessed June 20, 2025. https://www.investperak.gov.my/overview-perak/.

Teh, D. Y., S. N. Jaafar, and A. Asma. 2020. “Consumers’ knowledge and attitude towards Chinese herbal tea and consumption of Chinese herbal tea in selected district in Kedah.” Food Research 4, no. 3 (June): 666–73. https://doi.org/10.26656/fr.2017.4(3).327.

The Economic History of Malaysia. Accessed January 8, 2025. https://www.ehm.my.

Vijayan, S. 2022. “Ho Kai Cheong: Herbalist and Philanthropist of Ipoh.” FMT Lifestyle, November 15. https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/leisure/food/2022/11/15/ho-kai-cheong-herbalist-philanthropist-visionary-of-ipoh/.

Wong Hon Foong, Shih Chau Ng, Wen Tien Tan et al. 2019. “Traditional Chinese Medicine in Malaysia: A Brief Historical Overview of the Associations.” Chinese Medicine and Culture. https://doi.org/10.4103/CMAC.CMAC_20_19.

Wu Xu, Wnag Shengpeng, Lu Junrong et al. 2018. “Seeing the unseen of Chinese herbal medicine processing (Paozhi): advances in new perspectives.” Chinese Medicine 13, no. 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13020-018-0163-3.

Yeung, H. C. 2004. Chinese Capitalism in a Global Era: Towards a Hybrid Capitalism. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

Zafri, Z., and A. M. Morhalim. 2022. Perak State Economy & Its Potentials. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: MIDF Malaysia.

Zong, X. F., and G. Liscum. 1996. Chinese Medicinal Teas: Simple, Proven, Folk Formulas for Common Diseases & Promoting Health. United States: Blue Poppy Press.

Authors

Corresponding author: Dr. Su Qiuyang, mysunnysu@gmail.com

Su Qiuyang (https://orcid.org/0009-0005-4541-0681; BA, Sun Yat-sen University; MBA, Peking University; PhD Candidate, University of Malaya) has worked in the healthcare sector for many years as a senior manager and has authored a series of articles, interviews, and in-depth reports on culture and healthcare reform. Her current doctoral research at the University of Malaya focuses on the history of traditional Chinese medicine and its development among Overseas Chinese communities in Malaysia.

Prof. Danny Wong Tze Ken (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4357-7753) is Professor of History at the Department of History, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Universiti Malaya where he teaches history of Southeast Asia and History of China. His research interests include the Chinese in Malaysia, China’s relations with Southeast Asia and History of Sabah. He is currently Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Universiti Malaya. He was Director of Global Planning & Strategy Centre, Universiti Malaya and former Director of the Institute of China Studies and former Head of the Malaysian Chinese Research Centre at the same university.

Dr. Tan Miau Ing (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9129-6641; PhD Saharan Cina Malaysia, Universiti Malaya; M.Econ and B. Econ, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia) is Senior Lecturer of Department of History, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Malaya. She is also the Head of Malaysian Chinese Research Center (MCRC) of UM.