Mapping Ancient Medicines: Digital Tools Reveal Forgotten Drug Geographies in Early China

By Michael Stanley-Baker

Dr. Michael Stanley-Baker

Associate Professor, History and LKC Medicine

Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

ORCID: 0000-0001-6785-8501

Herbal drugs have long been valued not just for their effects, but where they come from. The origins of drugs are thought to be important indicators of their quality and their efficacy, and scholars and pharmacists around the world have paid attention to this for centuries. It is thus rare to find new data that allows us to rethink the early tradition in fundamental ways. An article of mine titled Mapping the Bencao, recently won an academic prize, so I thought I would write a brief summary of the article and its implications.

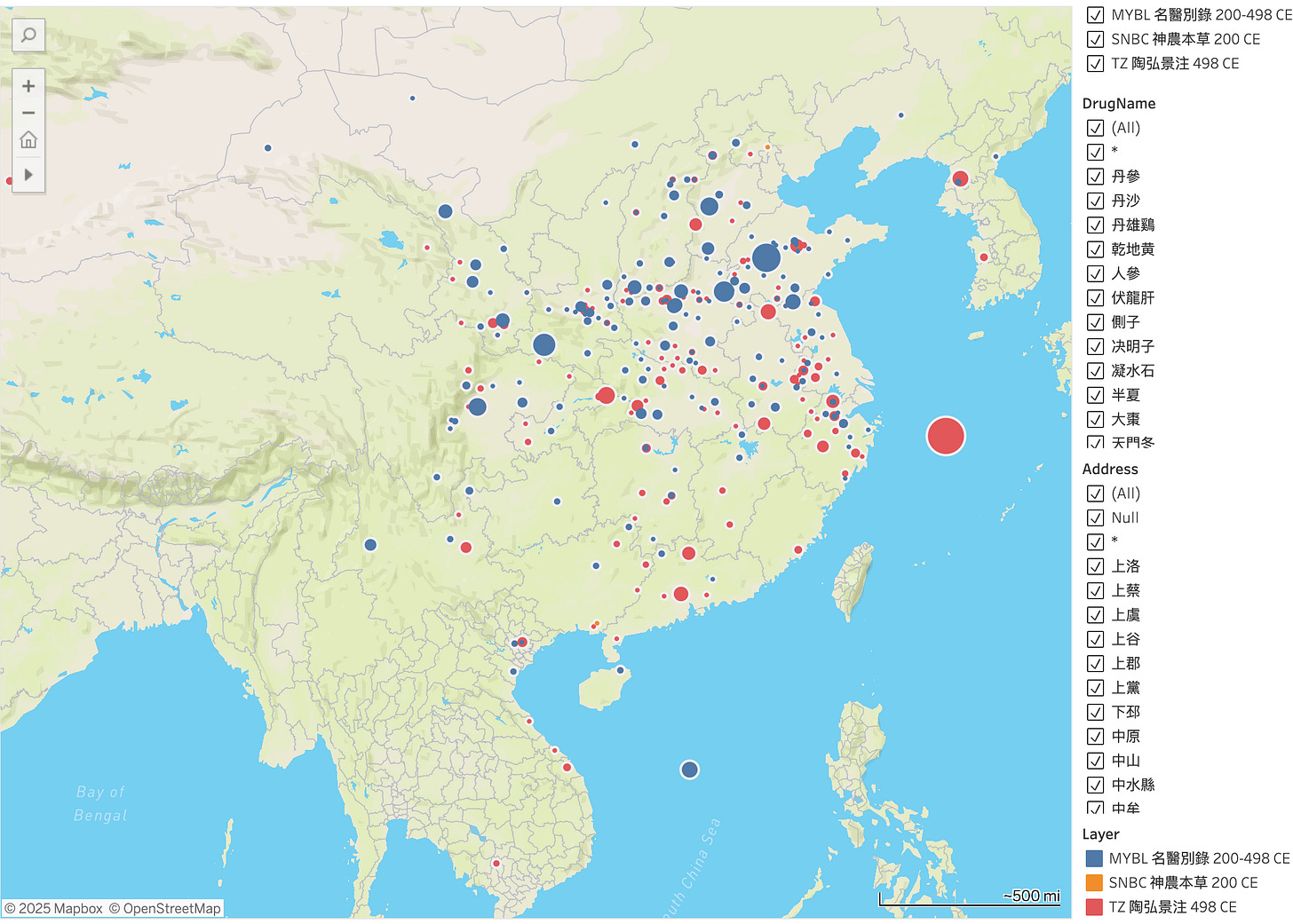

The study uses Digital Humanities to produce new data that challenges long-held assumptions about the origins and geography of Chinese materia medica. By digitally tagging a critical edition of an early Chinese pharmacological text, I was able to analyze its contents in new ways. In particular, by tagging it with historical GIS points, and rendering them in open-access platforms, I was able to produce maps of the locations where drugs were produced in early imperial China.

The practice of reading maps is very different from the way we encounter drug locations in a text. When reading a text, names pop up that may sound familiar or jog the memory, but for the most part, they fall into the background. You don’t get a sense of where they’re from, just the significance of the name of the place. The digital map however, reveals the geographic distribution of Chinese drug cultures in a way never before seen. It brings the drug locations into relationship with one another, and also in relationship to the local landscape. In particular, it showed a surprising fact—that almost all sites of production described in the texts were located on rivers or lakes, not on mountains, as imagined in the tradition.

At the heart of this study is the bencao 本草 tradition — China’s vast pharmacopoeia literature — and its multiple textual layers, especially the Materia Medica of the Divine Farmer, the Supplementary Records by Famous Physicians, and Tao Hongjing’s 陶弘景 Collated Annotations. Together with a team of colleagues, students and research associates, at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, National Taiwan University, Dharma Drum Institute of Liberal Arts and Nanyang Technological University, we created a digital, searchable edition of this layered text with the MARKUS and DocuSky platforms. Each entry is tagged for properties like taste, temperature, toxicity, preparation, and—crucially—place of origin. These tags were then matched to historical maps and GIS data from Academia Sinica, allowing researchers to visualise where drugs were sourced over time.

The resulting images tell a story that textual readings alone cannot. While scholars like Yamada Keiji had previously identified the loess plateau as the origin of Chinese drug lore, this map reveals a dense corridor of medicinal activity stretching along the Yellow River from the Bohai Sea through Chang’an (modern Xi’an), and into the Sichuan basin. This “Yellow River Corridor” turns out to be a riverine highway of drug trade and knowledge, connecting regions once thought peripheral to the canonical centers of Chinese medicine.

This view allowed me to rethink early drug lore not as a product of isolated Daoist mountain sages, but as a vibrant, decentralised network of drug production and exchange along rivers, mountains, and trade corridors. Because these sites were locations of trade rather than fixed points of botanical origin, the paper reimagines these locations as “drug production” sites — nodes of social-technological activity where wildcrafting, preparation, and trading translated these “wild objects”, or raw materials, into culturally legible medicinal products. Some places, like Taishan and Songshan, have long been famous in Daoist or medical traditions, but others — such as Hanzhong and Jianping — emerge in this study as waypoints in the drug trade. These places acted as bottlenecks or crossroads, showing that pharmacological knowledge flowed along human routes of exchange rather than solely sprouting from mountain hermitages or elite academies.

One particularly important case study is the recently excavated medical texts from Laoguanshan 老官山, near Chengdu in southwestern China. Though geographically distant from the central plains, the herbal repertoire of this tomb text is particularly concentrated in east and northeast China, especially Shandong province. This challenges assumptions about regional isolation and suggests that even in the 2nd century BCE, medical knowledge travelled widely. By comparing drug names in the Laoguanshan text with those found in the digitised bencao corpus, the paper argues that the Laoguanshan text reflects an eastern herbal vocabulary, perhaps preserved through trans-regional networks that may have navigated along the Yellow River.

Digital tools can radically transform how we understand traditional medical knowledge

One takeaway is that digital tools can radically transform how we understand traditional medical knowledge. Not only do they allow for granular philological tracking of drug names and their changes over time, but they also help visualise sociotechnical systems of exchange. I argue for moving beyond elite literary imaginations that saw drug knowledge as flowing from Confucian doctors or Daoist adepts. Instead, I encourage readers to see pickers, traders, sellers, and users — actors often marginalised by Confucian social mores —as part of a complex polyglot system where knowledge was dynamic, negotiated, and deeply embedded in place.

I also argue that this open-source data could be used for other kinds of research. For example, to look again at concentrations of regional trade, or to geo-locate literature, like poems or strange tales, that favour drugs from particular regions.

This work also speaks to present-day concerns in ethnopharmacology, bioprospecting, and data equity. Just as ancient Chinese physicians debated drug authenticity, modern researchers must wrestle with how traditional knowledge is extracted, named, and validated — often by those with the most institutional power. Through careful data stewardship and open-access publication, we can provide a more ethical and inclusive way to explore and share historical medical data.

Ultimately, Mapping the Bencao is more than a historical study. It’s a compelling case for how digital humanities can not only preserve the past but reconfigure our understanding of it. The rivers and roads that once carried herbs and recipes are now mirrored by data pathways and linked ontologies — but the questions remain the same: who knows what, where does knowledge live, and how do we value it?