Original guest post by Kenneth Zysk (University of Copenhagen)

I this paper I should like to revisit a problem in the history of Indian medicine, which is yet to find a satisfactory resolution. The issue centres on when and where Āyurveda came into existence and from where all or part of it could have derived, in a word, the origins of Āyurveda.

The Origins of Āyurveda

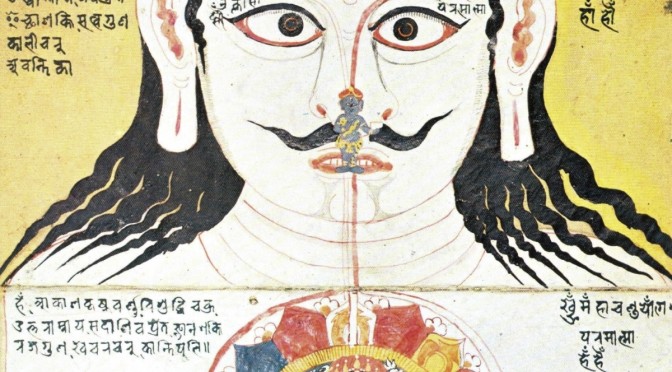

At the core of classical Āyurveda stands the aetiological theory of the three doṣas (tridoṣa), broadly defined as defilements of wind (vāta), bile (pitta), and phlegm (kapha). Disease is said to occur when for one or several reasons one or more of the doṣas moves from its seat to manifest someplace else in the body. On the surface of it, since the theory includes three well-defined Sanskrit terms, occurring together, it would seem to be a straightforward exercise to trace this transparent mode of thinking in Indian literature prior to the earliest medical treatises, in which the theory was first fully expounded. However, such has not been achieved and at present two opposing theories have been put forth for the origins of the three āyurvedic doṣas.

One maintains that the theory was wholly indigenous to the subcontinent, being embedded in early ideas of four of the five basic elements (mahābhūta): fire (agni) which characterises bile (pitta) and wind (vāyu), universal form of bodily wind (vāta); and perhaps also water (āp) and earth (pṛthivī), which characterise phlegm (kapha). The fifth element, space (ākāśa) is the realm of sound and does not easily fit to one of the doṣas. Sometimes it is paired with five to give bile. This analysis, however, occurs in the second level compilation found n Vāgbhaṭa’s seventh century Aṣṭāṅgahṛdaya Saṃhitā. It is also the point of view of most Indian scholars, while the other, advocated mainly by western scholars, posits that the theory is related to, if not dependent on, Greco-Roman medicine, since in its fundamental conceptual basis, Sanskrit doṣabears a similarity to Greek chymos, which gives rise to the four humours of black bile (melaina cholē), yellow bile (xanthē cholē), phlegm (phlegma), and blood (haima). While blood (rakta) is not counted in the list of three doṣas, Meulenbeld has shown that blood was considered in the same way as the doṣas in the classical Āyurveda.[1]The only missing pairing between Greek-Roman and Indian medicine is the doṣacalled “wind,” which was not one of the humours, but Greek pneumalike Sanskrit prāṇais found in a medical context.

Although Sanskrit doṣaoccurs in its original meaning of “defilement” or “fault” from the period of the early Upaniṣads (c. 800 BCE), its specific medical sense is first expounded in the Sanskrit treatises of Caraka and Suśruta. The medical notion of doṣacould not have come from nowhere, but from where and how.

Putting aside the two opposing points of view, I shall began afresh, starting with an examination of old literary sources in Sanskrit and working my way forward to the first systematic and composite treatises, the Carakaand Suśruta Saṃhitās, which date from around the first centuries before and after the Common Era.

Vedic Medicine

An early form of medicine was represented in the Vedic Saṃhitās from about 1300-800 BCE. Among these primarily religious treatises, there was no single text devoted exclusively to diagnosis and treatment of illness and malady; but rather randomly placed charms and incantations in verse were embedded in the earliest treatises of the Ṛgvedaand Atharvaveda for use in rituals to heal the sick and the suffering. The lack of a single text or texts dedicated to the subject of medicine indicated that healing was part of the overall socio-religious matrix in the earliest Sanskrit literature. On the other hand, only in its broadest underlying conceptual basis does a form of healing utilising incantations and rituals occur in the earliest āyurvedic treatises, especially in the context of maladies affecting children. Moreover, no direct linguistic parallels exist between the Vedic and āyurvedic incantations. This naturally implies that the āyurvedic aetiology of the three doṣas together with the extensive list of remedies based on it could not have derived solely from the medical theories and practices found in the early Vedas.

It must naturally also come from somewhere else. Could then part of the overall conceptual basis have derived from beyond the orbit of the Indian subcontinent, as several early western scholars of Indian medicine maintained? To try to answer this question, we must take the next histoical step and examine the literary sources composed between the Vedic hymns and the earliest medical works. My study therefore included an investigation of the later Vedic treatises of the Brāhmaṇas and Upaniṣads and the literature related to them. A deep study of these texts is still a desideratum, since I merely surveyed the principal texts. The cursory examination of them, however, revealed that there was little in the way of medicine that differed from that found in the Vedic Saṃhitās; and, moreover, there were still no individual texts devoted exclusively to medicine, with the exception of the formulation of the five bodily winds.

Although not a book per se, the fixed group of five bodily winds (apāna, prāṇa, vyāna, samāna, udāna) is a well-established idea that evolved from yogic practices involving breath control or prāṇāyamafirst mentioned in the early Upaniṣads and later picked up and medically altered by the early āyurvedic authors.[2] The occurrence of the doctrine of the five bodily winds in the medical treatises is simply not enough information to establish the later Vedic literature as the principle and only source for the three doṣas, and therefore it was not a viable place for further investigation. I turn my attention rather to a more promising literature, not in Sanskrit but in the Middle Indic language of Pāli, in which the earliest Buddhist scriptures were composed.

Buddhist Medicine

The Monastic Code or Vinaya Piṭaka of the Buddhist Pāli Canon contained a large section devoted to medicines, along with numerous references to healing theory and practice throughout the earliest parts of the Canon, which probably took shape some centuries before it was written down in Sri Lanka in about 29 BCE. This would place the Buddhist medical doctrines historically immediately prior to and contemporaneous with the earliest āyurvedic treatises.

In summary, these sources revealed the following major points. Already in Pāli Buddist literature there is found:

- a presumed understanding of the idea of the three doṣas;

- a practical approach to healing indicated in case histories and remedies;

- a legend of a famous healer, Jīvaka, which has travelled with Buddhism throughout Asia; and

- a clearly defined role of the healing arts in the early Buddhist monastery or Saṅgha.[3]

The content of the Buddhist medical theories and practices points to an important intermediate step in the evolutionary history of Indian medicine from Veda to Āyurveda. Moreover, the medical knowledge was preserved and transmitted not by composers and proponents of Brahmanic doctrines and beliefs, but by knowledgeable and literate ascetics living what appeared for the most part to be a mendicant’s lifestyle. The study of early Buddhist medicine made the Sanskrit tradition that was maintained and transmitted by the Brahmans, even a more unlikely source of early āyurvedic theories and practices.

But, does the Buddhist involvement in early Indian medical history bring us closer to finding the origins of Āyurveda? Only in so far as it localises elements of what later became āyurvedic medicine outside the Sanskritic orbit of brahmanic knowledge. Moreover, it shows that the aetiological tridoṣic theory was already well formulated by the time of earliest Buddhist scriptures. The “smoking gun” that provides the precise origin of the doctrines of Āyurveda is still wanting. So, for time being, we shall have to admit that a direct transmission from one medical text to another may never be found and moreover might never have occurred. Some might say “well then give it up and move on to something else.” I preferred, however, to be more creative and widen the sphere of investigation.

I started to look to other systems of thought and practice that are related but not central to medicine. These include systems of knowledge found in the Indian astral science or Jyotiḥśāstra, especially those parts that have some connection to medicine, such as the divinatory system of human marks or physiognomy.

Although these studies are ongoing, they so far indicate that at least part of the āyurvedic system of medicine in India was shared with other systems of Indian knowledge, which indicate also influence from non-Indian forms of thought in antiquity. Three important points come forth, which show

- a literary link between information in the early Sanskrit medical treatises and early Sanskrit astral literature;

- a fundamental similarity to systems of physiognomy from ancient Mesopotamia and from ancient Greece; and

- a possible dual role played by the Indian doctor as healer and diviner.[4]

Conclusions

Perhaps we shall never find the precise origins of the āyurvedic theory of the three doṣas and the methods of the cures based on it, but we have come closer to identifying possible, viable places to search for additional information. Moreover, I have become more and more convinced that we should not expect to find a single text or group of texts from which the early Sanskrit medical treatises were translated or on which they were based. Rather we should consider Āyurveda as a medical system that evolved under the influence of fruitful exchanges of important theories and practices of different kinds of healers, such as Jīvaka in the Buddhist legends. It is likely that the exchange continued for centuries at a time when contacts between different healers were possible. This would imply that the interaction was constant and lasted long enough for intellectual exchange and practical learning to take place and be recorded. For the time being, this is perhaps the more realistic approach to the origins of Āyurveda, which could allow us to speculate that the tridoṣa theory resulted from assimilation and adaption, where a Greco-Roman conception of the four humours blended with Indian philosophical notions of the three guṇas or qualities (sattva, rajas, and tamas) and thenfive basic elements (mahābhūta), both of which were well-known among proponents of Sāṃkhya, with whose philosophical notions the composers and compilers of the classical medical texts were conversant. The precise means by which the assimilation took place could indeed be a fruitful topic of exploration.

Bibliography

Meulenbeld, G. J. 1991. “The Constraints of Theory in the Evolution of Nosological Classifications: A Study on the Position of Blood in Indian Medicine (Āyurveda);” in G. J. Meulenbeld, ed. Medical Literature from India, Sri Lanka and Tibet (Leiden: E. J Brill): 91-106.

Zysk, K. 1991. Asceticism and healing in ancient India. Medicine in the Buddhist monastery. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Paperback: New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1991. Indian edition: Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1997, reprint, 2000. [Vol 2 of Indian Medical Tradition]. Second revised edition under preparation.

______________, 1993. “The science of respiration and the doctrine of the vital breaths in ancient India,” JAOS, 113.2: 198-213.

______________, 2000. “”Did ancient Indians have a notion of contagion?” in Lawrence I. Conrad and Dominik Wujastyk, eds., Contagion. Perspectives from Pre-Modern Societies(Aldershot, UK: Ashagate), 79-95.

______________. 2007. “The bodily winds in ancient India revisited.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.): 105-115.

______________. 2016. The India System of Human Marks. Text, translation, and notes. 2 Vols. Leiden: E.J. Brill [Sir Henry Wellcome Asian Series, Vol. 15].

______________ 2018. “Greek and Indian Physiognomics.” Journal of the American Oriental Society,138.2: 13-325.

Notes

[1]Meulenbeld 1991; cf. Zysk 2000.

[2]Zysk, 1993 and 2007.

[3]Zysk, 1991. I am happy to report that a revised, second edition of this study should be out soon with Motilal Banarsidass.

[4]Zysk 2016.1: 25-53; Zysk 2018.