This syllabus is part of the AMZ Syllabus Repository:

Category Archives: Chinese & East Asian Medicines

[SYLLABUS] Chinese Medical Tradition

This syllabus is part of the AMZ Syllabus Repository:

[SYLLABUS] History of Food in China

This syllabus is part of the AMZ Syllabus Repository:

[SYLLABUS] History of Chinese Medicine

This syllabus is part of the AMZ Syllabus Repository:

[SYLLABUS] Medicines, Poisons, and Foods: Material Culture of Medicine in China and Europe

This syllabus is part of the AMZ Syllabus Repository:

A Brief Review of Related Issues on the Problematic Tang Ye Jing 湯液經

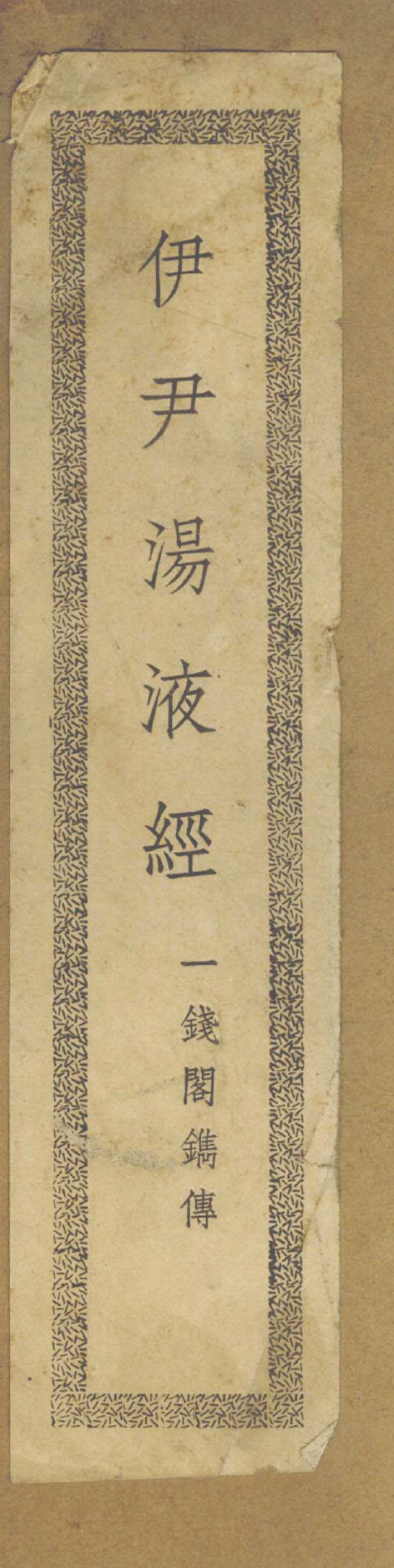

The title printed on the front cover, i.e. Yi Yin Tang Ye Jing 伊尹湯液經 (Yi Yin’s Classic of Decoction). Below the title are the five characters ‘Yi Qian Ge Juan Zhuan 一錢閣鐫傳’ (Engraved and Issued by the One-Coin Pavilion).

A guest blog by Di Lu

Many scholars and practitioners of Chinese medicine now consider the Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction) as the basic reference for Zhang Ji’s 張機 (style name: Zhongjing 仲景, c. 150-219 AD) Shang Han Lun 傷寒論 (Discourse on Cold Damage). But is such an opinion on the relationship between the two texts unquestionable?

On the Anonymous Text Tang Ye Jing Fa 湯液經法 (Models of the Classic of Decoction)

The Tang Ye Jing (Classic of Decoction) has long been lost since the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 AD). The ‘Yiwen Zhi 藝文志’ (Bibliographical Treatise) of the Han Shu 漢書 (History of the [Former/Western] Han Dynasty, c. late 1st century and early 2nd centuries AD) simply records the Tang Ye Jing Fa 湯液經法 (Models of the Classic of Decoction, in 32 juan 卷 [volumes], without author information), and groups it with the other ten medical works under the title of jing fang 經方 (classical prescriptions). Many later authors mentioned the bibliographic record of this text in the Han Shu (Book of Han); but none of them reported his/her reading of the text (strictly under the title of ‘Tang Ye Jing Fa’, or under a similar title [e.g. Tang Ye Jing 湯液經] but containing the same number of volumes), or introduced the content of the text.

On the Text Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction) by Yi Yin 伊尹

At least from the Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279 AD) onward, so far as known, authors of Shi Wu Ji Yuan 事物紀原 (Origins of Things and Matters, first printed in 1197 AD), Yi Shui 醫說 (Discourse on Medicine, 1224 AD) and other works attributed the text entitled Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction; NOTE: lacking the character fa 法) to Yi Yin 伊尹 (c. 1649- c. 1549 BC), without offering any reasons or additional information, without basing such a claim on the above bibliographic record in the Han Shu (History of the [Former/Western] Han Dynasty). But similarly, no one in pre-modern China left a bibliographic record of this text, and/or spoke of any specific content of the text. Did this Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction) ever exist? If so, is it the same as the Tang Ye Jing Fa 湯液經法 (Models of the Classic of Decoction)? If so, why does the above bibliographic record in the Han Shu (History of the [Former/Western] Han Dynasty) not ascribe authorship to Yi Yin?

On Yi Yin’s 伊尹 Authorship of Tang Ye 湯液 (Decoction), Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 and Tang Ye Jing Fa 湯液經法

Modern proponents of the Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction) as the progenitor of Zhang Ji’s Shang Han Lun 傷寒論 (Discourse on Cold Damage), as mentioned above, often invoke the following words in Huangfu Mi’s 皇甫谧 (215-282 AD) preface to his own work Zhen Jiu Jia Yi Jing 鍼灸甲乙經 (Classic of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, Selected and Arranged):

Zhong Jing Lun Guang Yi Yin Tang Ye Wei Shi Shu Juan, Yong Zhi Duo Yan.

仲景論廣伊尹湯液為十數卷, 用之多驗.

[Zhang] Zhongjing expanded Yi Yin’s Decoction into more than ten volumes, which were mostly effective in practice.

Lin Yi’s 林億 (active in the 11 century AD) preface to Zhang Ji’s Shang Han Lun (Discourse on Cold Damage) adopts the above words of Huangfu Mi, and adds that ‘Zhong Jing Ben Yi Yin Zhi Fa 仲景本伊尹之法’ ([Zhang] Zhongjing’s [medical knowledge] is rooted in Yi Yin’s norms). The proponents often acquiesce in the equation of the Tang Ye 湯液 (Decoction) with the Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction) or Tang Ye Jing Fa 湯液經法(Models of the Classic of Decoction). In this way, Tang Ye (Decoction) becomes an abbreviation of the latter text title; and Yi Yin also becomes the author of Tang Ye Jing Fa 湯液經法 (Models of the Classic of Decoction).

However, Tang Ye Jing Fa 湯液經法 (Models of the Classic of Decoction) consists of 32 juan 卷 (volumes); while Zhang Zhongjing’s expanded edition of Yi Yin’s Tang Ye 湯液 (Decoction) merely contain more than ten juan 卷 (volumes). How could Yi Yin’s Tang Ye 湯液 (Decoction) or Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction) be the same as the anonymous Tang Ye Jing Fa 湯液經法 (Models of the Classic of Decoction)? Why do extant editions of Zhang Ji’s preface to his own work Shang Han Lun (Discourse on Cold Damage) contain no words of the text Tang Ye 湯液 (Decoction), Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction), or Tang Ye Jing Fa 湯液經法 (Models of the Classic of Decoction)?

![Copyright page A, showing the book title Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction), the words ‘Yang Shao Yi Fu Zi Kao Ci 楊紹伊夫子考次’ (Compiled by Teacher Yang Shaoyi) and ‘Di Zi Li Ding Jing Shu 弟子李鼎敬署’ (Respectfully Signed by [Yang’s] Student Li Ding).](https://static1.squarespace.com/static/537fb379e4b0fe1778d0f178/t/5c85c4dde2c48349ec80a51b/1552270582752/2+Tang+Ye+Jing+Page+1.jpg?format=1000w)

Copyright page A, showing the book title Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction), the words ‘Yang Shao Yi Fu Zi Kao Ci 楊紹伊夫子考次’ (Compiled by Teacher Yang Shaoyi) and ‘Di Zi Li Ding Jing Shu 弟子李鼎敬署’ (Respectfully Signed by [Yang’s] Student Li Ding).

On the Reconstruction of Yi Yin’s Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 in 1948

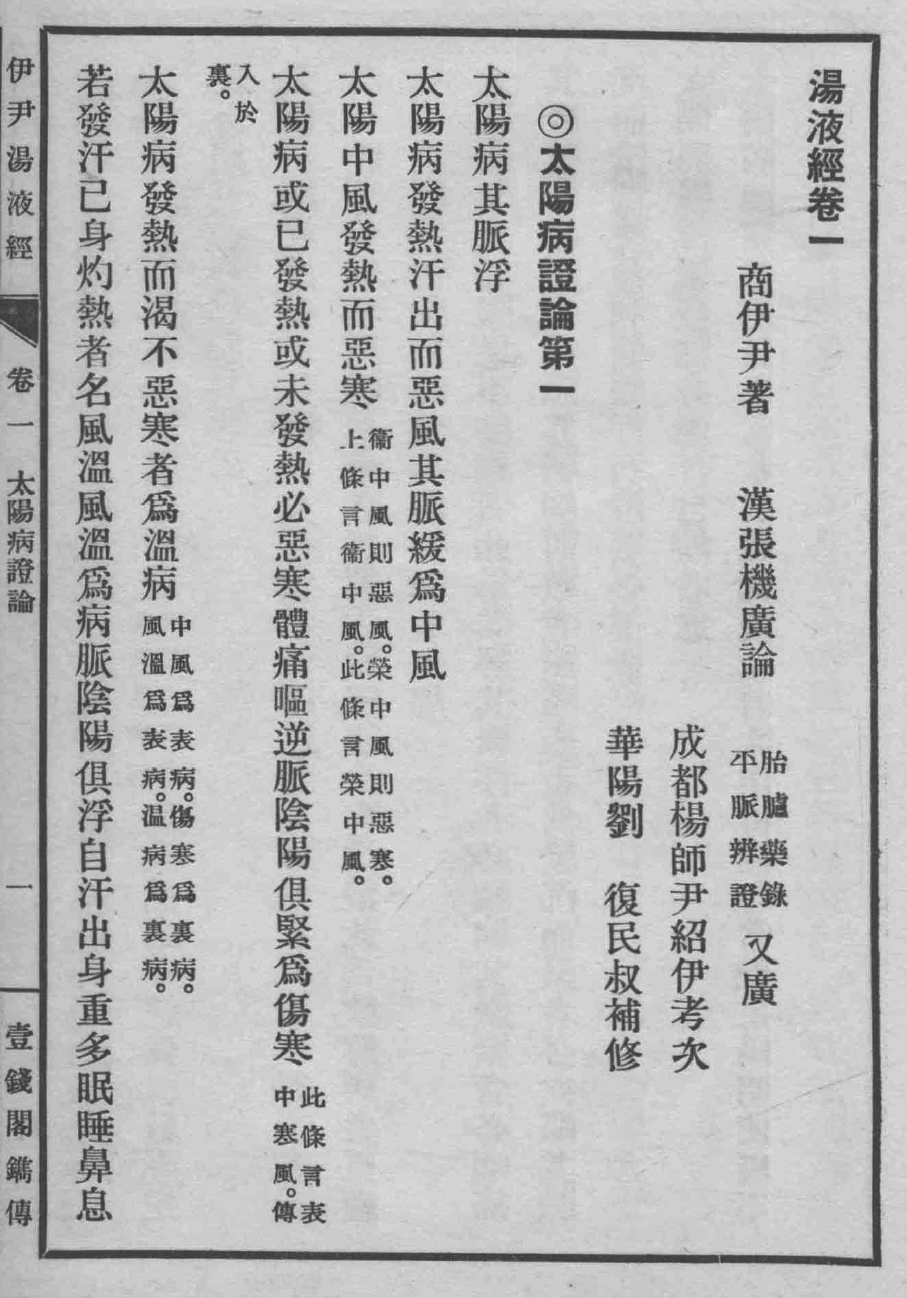

In 1948, Yang Shiyin’s 楊師尹 (style name: Shaoyi 紹伊, 1888-1949) reconstruction of Yi Yin’s Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction), supplemented by Liu Fu 劉復 (style name: Minshu 民叔, 1897-1960), was published by Liu’s Yiqian Ge 一錢閣 (One-Coin Pavilion). This is the only reconstruction of the text Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction), which is believed by some people to be written by Yi Yin, and/or to have truly existed and given birth to Zhang Ji’s Shang Han Lun (Discourse on Cold Damage). Its main text has 160 pages.

The book title printed on the front cover of this reconstruction is ‘Yi Yin Tang Ye Jing 伊尹湯液經’ (Yi Yin’s Classic of Decoction); while the title shown on the copyright pages and the first page of the main text is ‘Tang Ye Jing 湯液經’ (Classic of Decoction).

All images here are from the original edition (1948) of the reconstruction of the Yi Yin Tang Ye Jing 伊尹湯液經 (Yi Yin’s Classic of Decoction) or Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction) in 1948.

The 1948 reconstruction of the Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction) now has the following two modern versions (the latter one has adjusted the original title to another):

- Yi Yin Tang Ye Jing 伊尹湯液經 (Yi Yin’s Classic of Decoction), in: Liu Min Shu Yi Shu He Ji 劉民叔醫書合集 (Collection of Liu Minshu’s Medical Works), Chen Guangtao et al. (eds.), Tianjin: Tianjin Kexue Jishu Chubanshe, 2011, pp. 201-345.

- Tang Ye Jing Gou Kao 湯液經鈎考 (A Study of the Collected Text of the Classic of Decoction), Chen Juwei and Guo Yujing (eds.), Forewarded by Qiu Hao, Beijing: Xueyuan Chubanshe, 2011, Pp. 242.

Yang Shiyin’s 楊師尹 (style name: Shaoyi 紹伊) name indicates Yang’s admiration of Yi Yin. Literally, Shiyin 師尹 means imitating [Yi] Yin; and Shaoyi 紹伊 means introducing Yi [Yin]. According to Yang Shiyin’s own introductory chapter in the reconstructed text,

The first page of the main text, showing the following information: ‘Shang Yi Yin Zhu 商伊尹著’ (Written by Yi Yin of the Shang Dynasty), ‘Cheng Du Yang Shi Yin Shao Yi Kao Ci 成都楊師尹紹伊考次’ (Compiled by Yang Shiyin of Chengdu, whose style name is Shaoyi), and ‘Hua Yang Liu Fu Min Shu Bu Xiu 華陽劉復民叔補修’ (Supplemented by Liu Fu of Huayang, whose style name is Minshu).

- the full title of the text Tang Ye 湯液 (Decoction) mentioned by Huangfu Mi should be Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction);

- the author of the Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction) was Yi Yin of the Shang dynasty (c. 1600-1046 BC);

- the Tang Ye Jing Fa 湯液經法 (Models of the Classic of Decoction, 32 volumes) was a later text composed on the basis on Yi Yin’s Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction) and containing all the content of the latter;

- the Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction) still existed in the Eastern Han dynasty, and enabled Zhang Ji to read it and expand its content; Shang Han Lun (Discourse on Cold Damage) was not ‘written’ by Zhang Ji, but an expansion of the Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction);

- Yang Shiyin’s reconstruction of the text Tang Ye Jing 湯液經, alleged by Yang to be comprised of Yi Yin’s Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction) and extended words by Zhang Ji, was reconstructed on the basis of Wang Shuhe’s 王叔和 (c. 210-285 AD) Mai Jing 脈經 (Classic of the Pulse) and Sun Simiao’s 孫思邈 (581-682 AD) Qian Jin Yi Fang 千金翼方 (Supplement to Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Gold, c. 682) (Wang and Sun’s texts contain words from Zhang Ji’s Shang Han Lun [Discourse on Cold Damage]).

The above points are arbitrary and speculative. None of them is solidly convincing. In particular, the Mai Jing (Classic of the Pulse) adverts to neither Yi Yin nor the Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction). And only the 26th chapter of the Qian Jin Yi Fang (Supplement to Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Gold) mentions ‘Gu Ren Yi Yin Tang Ye 古人伊尹湯液’ (the ancient man Yi Yin’s Decoction), which, however, is not connected with origins of the content of the Qian Jin Yi Fang. Moreover, as mentioned above, extant editions of Zhang Ji’s preface to his Shang Han Lun (Discourse on Cold Damage) also makes no mention of the text Tang Ye 湯液 (Decoction), Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction), or Tang Ye Jing Fa 湯液經法 (Models of the Classic of Decoction). Some scholars also treat Yang’s opinions, methodology and reconstruction with caution, as evidenced by Qiu Hao’s foreword to the Tang Ye Jing Gou Kao 湯液經鈎考 (A Study of the Collected Text of the Classic of Decoction, Chen Juwei and Guo Yujing eds., Beijing: Xueyuan Chubanshe, 2011, pp. 1-16) and Feng Shilun’s foreword to the Jie Du Yi Yin Tang Ye Jing 解讀伊尹湯液經 (Interpreting Yi Yin’s Classic of Decoction, Feng Shilun 馮世綸 ed., Beijing: Xueyuan Chubanshe, 2009, pp. i-iv).

On the Manuscript Fu Xing Jue Zang Fu Yong Yao Fa 輔行訣臟腑用藥法要 (Auxiliary Knacks of Essential Drug Usage for Viscera)

A text often associated with academic discussions of the Tang Ye Jing Fa 湯液經法 (Models of the Classic of Decoction) is the manuscript Fu Xing Jue Zang Fu Yong Yao Fa 輔行訣臟腑用藥法要 (Auxiliary Knacks of Essential Drug Usage for Viscera, hereinafter FXJ), which is now included in, for example, the Dun Huang Gu Yi Ji Kao Shi 敦煌古醫籍考釋 (Commentary and Research on Ancient Medical Texts Excavated in Dunhuang, Ma Jixing 馬繼興, ed., Nanchang: Jiangxi Kexue Jishu Chubanshe, 1988, pp. 115-137), Dun Huang Shi Ku Mi Cang Yi Fang 敦煌石窟秘藏醫方 (Secret Medical Prescriptions from Dunhuang Grottoes, Wang Shumin, ed., Beijing: Beijing Yike Daxue & Zhongguo Xiehe Yike Daxue Lianhe Chuban, 1998, pp. 1-28), Fu Xing Jue Zang Fu Yong Yao Fa Jiao Zhu Kao Zheng 《輔行訣臟腑用藥法要》校注考證 (Textual Studies, Collation and Annotations of the Auxiliary Knacks of Essential Drug Usage for Viscera, Wang Xuetai, ed., Beijing: Renmin Junyi Chubanshe, 2008, pp. 3-62), and Fu Xing Jue Zang Fu Yong Yao Fa Jiao Zhu Jiang Shu 《輔行訣五臟用藥法要》校注講疏 (Interpretation, Collation and Annotations of the Auxiliary Knacks of Essential Drug Usage for Viscera, Yi Zhibiao, et al., eds., Beijing: Xueyuan Chubanshe, 2009, pp. 250-307).

According to the introductory remarks on FXJ in the above modern publications, FXJ was initially preserved at the Mogao Grottoes of Dunhuang, and then flowed into the hands of a Daoist, who later sold it to the Chinese physician Zhang Wonan 張偓南 at the beginning of the Republican period (1912-1949). Zhang passed the original manuscript of FXJ down to his grandson Zhang Dachang 張大昌, also a Chinese physician. In the summer of 1966, unfortunately, the original manuscript was destroyed in the Cultural Revolution. In 1974, Zhang Dachang sent a copy of the manuscript to the Zhong Guo Zhong Yi Yan Jiu Yuan 中國中醫研究院 (China Academy of Chinese Medicine). Later, the manuscript began to receive increasing attention from historians of medicine. Until now, 21 copies of the original manuscript of FXJ, transcribed by different people in the second half of the 20th century, have been found in China and included in the Fu Xing Jue Wu Zang Yong Yao Fa Yao Chuan Cheng Ji 《輔行訣五藏[臓]用藥法要》傳承集 (Collection of the Circulated Manuscripts of the Auxiliary Knacks of Essential Drug Usage for Viscera, Beijing: Xueyuan Chubanshe, 2008, pp. 3-400).

FXJ, originally authored by Tao Hongjing 陶弘景 (456-536), is a controversial manuscript. Two historians of Chinese history, namely Zhang Zhenglang 張政烺 and Li Xueqin 李學勤, had examined FXJ, and concluded that it could not be counted as an early writing composed by Tao Hongjing, nor could it be a modern forged text. The original manuscript of FXJ is now lost; and available information on the origin of FXJ originates from Zhang Dachang, whose narrative might be unreliable (say, FXJ might be forged or might not be a manuscript from Dunhuang Grottoes). The title of FXJ also does not appear in extant records of Tao Hongjing’s writings. Some scholars treat FXJ a forged text, see, for example, Tian Yongyan 田永衍, ‘Fu Xing Jue Zang Fu Yong Yao Fa Yao Fei Cang Jing Dong Yi Shu Kao——Cong Wen Ben Xing Shi Yu Wen Xian Guan Xi Kao Cha 《輔行訣臟腑用藥法要》非藏經洞遺書考——從文本形式與文獻關係考察 (A Study of the Auxiliary Knacks of Essential Drug Usage for Viscera as a Text not from Dunhuang Grottos——From the Perspectives of Textual Forms and Relationships)’, Nan Jing Zhong Yi Yao Da Xue Xue Bao (She Hui Ke Xue Ban) 南京中醫藥大學學報(社會科學版) (Journal of Nanjing University of TCM [Social Science]), 2015, 16(4): 232-237.

FXJ mentions ‘Tang Ye Jing Fa 湯液經法’ (Models of the Classic of Decoction) three times, and claims that it was written by Yi Yin of the Shang dynasty. Because of this, some historians, such as Ma Jixing 馬繼興, consider that FXJ incorporates some words from the Tang Ye Jing Fa 湯液經法 (Models of the Classic of Decoction). Further, because some prescriptions recorded in FXJ (not associated with the Tang Ye Jing Fa 湯液經法 [Models of the Classic of Decoction]), bear resemblance to their counterparts in Zhang Ji’s Shang Han Lun (Discourse on Cold Damage), some historians of medicine, such as Qian Chaochen 錢超塵, think that FXJ proves Shang Han Lun (Discourse on Cold Damage) to be composed on the basis of Tang Ye Jing Fa 湯液經法 (Models of the Classic of Decoction). Even if FXJ is not a forged text, such an opinion is still too arbitrary.

Concluding Remarks

![Copyright page B, showing the publisher information ‘Liu Shi Yi Qian Ge Zeng Fu Zhen Juan Zhuan Chuan 劉氏一錢閣曾福臻鐫傳’ (Engraved and Issued by Zeng Fuzhen at Liu’s One-Coin Pavilion), and the information on the transcriber and the collator: ‘Di Zi Li Ding Lu Gao 弟子李鼎録稿’ (Transcribed by [Yang’s] Student Li Ding) and ‘Wu Zi Nian Dong Chu Ban Hai Men Shen Dan Jiao Zi 戊子年冬初版海門沈旦校字’ (First Published in the Winter of 1948, Collated by Shen Dan of Haimen).](https://static1.squarespace.com/static/537fb379e4b0fe1778d0f178/t/5c85c67de5e5f02ba2f5b176/1552270984156/3+Tang+Ye+Jing+Page+2.jpg?format=1000w)

Copyright page B, showing the publisher information ‘Liu Shi Yi Qian Ge Zeng Fu Zhen Juan Zhuan Chuan 劉氏一錢閣曾福臻鐫傳’ (Engraved and Issued by Zeng Fuzhen at Liu’s One-Coin Pavilion), and the information on the transcriber and the collator: ‘Di Zi Li Ding Lu Gao 弟子李鼎録稿’ (Transcribed by [Yang’s] Student Li Ding) and ‘Wu Zi Nian Dong Chu Ban Hai Men Shen Dan Jiao Zi 戊子年冬初版海門沈旦校字’ (First Published in the Winter of 1948, Collated by Shen Dan of Haimen).

After a brief review of related issues on the Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction), we can confirm that:

- There had been an anonymous text entitled Tang Ye Jing Fa 湯液經法 (Models of the Classic of Decoction, in 32 juan [volumes]) in the Western Han dynasty;

- It is unknown whether there truly existed a text written by Yi Yin of the Shang dynasty and entitled Tang Ye 湯液 (Decoction) or Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction);

- It is unknown whether the Tang Ye Jing Fa 湯液經法 (Models of the Classic of Decoction) was Yi Yin’s Tang Ye 湯液 (Decoction) or Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction);

- It is unknown whether Zhang Ji’s Shang Han Lun (Discourse on Cold Damage) was an expansion of Yi Yin’s Tang Ye 湯液 (Decoction) or Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction);

- Yang Shiyin’s reconstruction of Yi Yin’s Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction), published in 1948, can only represent his own faith in the existence of Yi Yin’s Tang Ye Jing 湯液經 (Classic of Decoction).

Purple Cloud Podcast: Daoists and Doctors: Michael Stanley-Baker

In this episode Daniel interviews Michael Stanley-Baker about his in depth study of the spiritual and medical practices of the Shang Qing school of Daoism. The podcast delves into the relationship between religion and medicine, the visualisation and meditation techniques of the Shan Qing practitioners and touches on the roles of played by important figures such as Ge Hong and Tao Hong Jing. Listen to the show here!

Can use of acupuncture delay proper medical treatment?

Introduction

Even though there is room for more thorough adverse effect reporting in acupuncture trials and a need for more studies about acupuncture safety (Ng et al. 2016; Turner at al. 2011), there already exists evidence concerning the safety of acupuncture. Based on the studies (Witt et al. 2009; Kim et al. 2016; McCulloch et al. 2015; Park et al. 2014; Houzé et al. 2017), we can conclude that generally acupuncture can be seen as a relatively safe practice. The adverse effects from acupuncture are extremely rare compared to reported adverse effects from conventional medicine. The FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) Public Dashboard reveals 906,773 serious side effect reports and 164,154 deaths from side effects or malpractice in 2017 alone. This is an unfair comparison as the patient base and seriousness of the conditions treated are often very different, but it gives us a perspective to the safety of acupuncture in comparison with many other medical treatments. And even the most serious side effects like pneumothorax from acupuncture seem to be preventable with sufficient training in acupuncture education (Kim et al. 2016).

In the acupuncture studies about patient safety, the subject has been approached from the point of safety of the treatment itself. There seems to be a lack of studies about the possibility of delayed medical treatment in cancer or other severe medical conditions due to the use of acupuncture. This essay approaches the subject with reflection on a patient case.

Case background

The author first met the patient in 2011. The patient had suffered from recurring, almost constant uveitis for 15 years. Known causes of uveitis had been previously excluded by medical doctors. The only treatment offered to the patient was ophthalmic steroids. Prolonged use of the steroids had increased her intraocular pressure causing glaucoma that threatened her diminishing vision. The ophthalmologist wanted to start a more robust and constant medication for glaucoma with a drug having the side effect of flaring of uveitis. The patient wanted to try acupuncture as an alternative.

After five sessions of acupuncture, the symptoms of uveitis had clearly decreased and she had reduced the use of corticosteroids. She had permission from the ophthalmologist to dose corticosteroids based on need. During the following months, she used them only twice when she felt any peculiar feelings in her eyes. Five months later she visited her ophthalmologist who could not see any signs of uveitis. Due to increased intraocular pressure, they had agreed for regular follow-ups. Beside one occasion in 2012, she has been without corticosteroids and free from uveitis.

In addition to uveitis, she had a medical history of back and joint pains, and Ménière’s disease.

During her initial visits to author’s clinic, she expressed her growing frustration with medicine and how she felt like a test subject. The doctors could not give a reason for her symptoms, and to her it seemed illogical to use medication causing uveitis to treat problems caused by the medication for uveitis. She also felt that some doctors she had met had been unprofessional in their behaviour. Side effects and dissatisfaction to conventional health care are among common reasons for trying acupuncture (Jakes et al., 2014).

Radical change in patient’s health

In 2015, the patient wanted to try acupuncture for fatigue. She had already visited a medical doctor through occupational health care who didn’t find anything alarming. The author performed acupuncture based partly on her previous background information and her current symptoms. Afterwards, she reported a slight initial improvement, but the exhaustion soon returned and was non-responsive to further attempts with acupuncture.

After a third acupuncture treatment she caught a flu and visited another doctor who took a chest X-ray that revealed a cancerous growth in her lungs. The patient was treated with surgical removal of the tumour. Because of inappropriate joking by the operating doctor just before the surgery, she felt mistreated again even though the surgery was successful. Soon after the surgery she contracted pneumonia. During follow-ups later on, her papers were not read properly leading to surgical marks visible in the X-ray to be mistaken as a sign of pulmonary embolism. Two months of unnecessary subcutaneous injections added to her mistrust of the whole medical profession even though the surgery itself had been successful.

During these events the patient contacted the author and told him about the correct diagnosis. She didn’t blame the author for misdiagnosis. But for the author this caused concerns and a need for reflection. How could something this serious be missed even when the cancer was advanced enough to cause serious fatigue? Could this be prevented from happening again?

Meeting in 2017

In 2017, the patient reserved time from the author because of vertigo caused by Ménière’s disease. The prescribed medication was no longer effective. During the meeting she gave a detailed account of her experience with surgery and how she felt afterwards. She was angry and frustrated and said she had little faith left for the health care system even though she had been saved by the medical procedure. During the session she gave permission for using her case as a case study. After giving the permission, she was told that the treatments would be free of charge.

Meeting her after the incident produced conflicting thoughts. Because of her past, the current condition felt more alarming. Why did her medication suddenly stop working? Was the dizziness caused by Ménière’s disease, a simple benign positional vertigo or was it something more severe? What if this was somehow connected to her previous condition? There was also curiosity and a need to ask questions about her previous health concerns that might shed some light to the author’s wrong diagnosis.

She had already seen her physician to screen out anything serious but still the situation stirred some insecurity in the author. During the discussion and diagnosis she revealed that she had recently lost her job and was now unemployed. So she was particularly happy to receive free treatments. Lack of money combined with free treatments might also increase the possibility of an already vulnerable patient to feel more dependent on the acupuncturist or it could produce a feeling of groundless gratitude. Having less money might also mean that she might be less willing to see a doctor in case the acupuncture treatment did not work, especially with her experiences with the public health care.

While describing her experiences and expressing her mistrust with the medical profession, she didn’t seem to consider the author to be part of the medical profession. In Finland, the author is a registered health care professional due to being a licensed masseur, but an acupuncturist is not an accepted health care professional nor is there any legal regulation about the profession. The professional associations are working to self-regulate the field, set educational criteria, enforce the following of ethical guidelines, and ensure that the professionals have proper insurances.

For the author, it was important to meet the patient face to face after making a wrong diagnosis. There were no signs of blaming or mistrust from the patient. Her patient records had been reviewed in 2015 and again before the appointment. There was no evidence of neglecting of symptoms, and she had already visited a medical doctor beforehand. It was crucial for the improvement of practice for the author to become more aware of possible consequences. It made the author question his own responsibilities and also the boundaries of his practice.

Analysing the case

During 2015, the author had failed to recognize lung cancer. The examination and questions asked during the visit could have been more thorough. Owing to the fact that the patient was previously known, there was a possibility of using information gathered during earlier visits. This combined with the shorter time reserved for returning patients might have made it harder to be cautious enough. The TCM diagnosis based on the discussion, pulse, and tongue during the visit revealed what is known in Chinese medicine as a deficiency of blood and a weakness of lung qi. Relying on the patient history while formulating a picture of the current situation might have affected the understanding of the real reason for exhaustion and how serious her case was. The medical expertise of the author did not enable him to recognise the underlying reason. A similar mistake was probably made by the medical doctor in occupational health care who failed to see cause for further tests. Given the patient’s earlier bad experiences with health care, she probably might not easily go back for a second opinion. In this case, it was pure luck that the patient caught the flu and was sent to x-ray.

The seriousness of the situation also raises other concerns. What if the patient had gotten better results from the acupuncture treatment? In that case, could the better results have delayed a proper diagnosis and medical treatment? And what role does the therapeutic relationship play in a possible delay of proper treatment?

There exists some evidence that acupuncture is effective in treating cancer-related fatigue (Duong et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2018; Zick et al. 2016). These studies focus on fatigue in connection with conventional cancer treatments, but acupuncture might also diminish the fatigue caused by cancer itself. Definite scientific evidence for the effectiveness of acupuncture for cancer pain is still lacking (Wu et al. 2015), but there is reason to believe that acupuncture might provide some relief from cancer pain (Hu et al. 2016; Chiu et al. 2017). So there is a possibility that acupuncture might prolong the time before the patient goes to see a doctor. An acupuncturist might see diminished fatigue and/or pain as evidence of successful treatment, which might in reality delay proper medical treatment. However, in case of pain, the same could easily happen with self-administered and commonly available pain killers. The fatigue might also diminish with energy drinks (Warnock et al. 2017), but the effects wouldn’t probably last for long. However, it could also be possible that by visiting an acupuncturist frequently, the acupuncturist could notice if there was no response to treatment or that the results were not as long-lasting as they should be. At least the acupuncturist would notice if the condition of the patient seemed to deteriorate despite the treatments. This could easily alarm a professional acupuncturist so, in this way, the acupuncturist would provide an extra pair of eyes watching for the patient’s health. In Finland, the acupuncture associations require the signing of ethical conduct which states that all acupuncturists refer cases to medical doctors when medical treatment is needed.

A study by Shorofi and Arbon (2017) offered some reasons why patients are opting to use CAM therapies instead of medical therapies. In the study, in all the people opting for CAM therapies, the most relevant reasons for this case study were that the problem was not seen serious enough to see a doctor (21.4%), a belief that these alternative treatments have fewer side effects than conventional ones (16.9%), and dissatisfaction with conventional treatments (6.8%). Combining these percentages with those of people who felt that CAM therapies were more fitting to their personal lifestyle or philosophy (37.7%), there is some evidence of a group of people who might not prefer to see a medical doctor in the first place. The study was done among hospitalised patients in Australia, but the author is in agreement over these patient groups and confirms similar numbers based on his own patient records and experience.

In serious diseases, like cancer in this case, medical diagnosis and intervention as early as possible is paramount. The symptoms, however, can begin with only minor health complaints. The 21.4% of population who use complementary modalities consider their problems not serious enough (Shorofi and Arbon 2017), but they might still find their way to the acupuncturist who, with adequate training, could be able to recognise the severity of the symptoms and could advise the patient to see a doctor.

The example patient in this essay had a medical diagnosis from her ophthalmologist for her previous condition. But in Finnish acupuncture clinics, it is very common to meet patients with medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS). These patients do not have a diagnosis and often feel that in conventional medical care they are misunderstood and their symptoms are not always taken seriously (Lipsitt et al. 2015). This same patient group generally obtains poor clinical outcomes from medical practice (Lipsitt et al. 2015), which might lead them to further avoid medical doctors. Some of these patients might feel more understood by CAM practitioners in general. Depending on the type of therapy, this could partly be due to the duration of initial interview and time used during the treatment, or more cosy clinical settings. It might be the CAM practitioner who first notices that their symptoms start to change or become worse, signalling that there might be a need to see a doctor. However, if the CAM therapist fails to see the alarming signs, the patient might get non-optimal treatment and believe that he gets all the treatment he needs. This could be preventable with proper education and further cooperation with medical doctors.

An even more alarming group than the MUPS patients who often burden health care with their constant visits (Lipsitt et al. 2015), are those who feel very dissatisfied with their medical care and are avoiding seeing doctors. This group is easily left without treatment by their own choice. Some of these patients might still be willing to see an acupuncturist. In that case, more serious and easily recognised problems might become apparent and they could be referred to health care, if they can be persuaded to make an appointment. Within these patient groups, there are people who feel vulnerable and, sometimes, they do not know where they should go and which symptoms they should tell their doctors. In their case, even one bad experience with a medical doctor can lead to further aversion of medical procedures and tests. For them an acupuncturist might be seen as a neutral bridge for communication to conventional health care.

CAM modalities are also often selected because of recommendations or wanting self-control over an illness (Shorofi and Arbon 2017). Many patients from the group who feel CAM therapies are more fitting to their personal way of life may not easily visit a doctor for any minor complaints. Based on the author’s experience, the people from these groups are generally willing to see a doctor when faced with any serious conditions or when told so by an acupuncturist. The problem for these patients is to recognise what is relevant and what is serious enough. Those seeing an acupuncturist with at least a basic education of medicine, could then be told by the acupuncturist to see a doctor if needed.

Conclusions

The failure to recognise lung cancer by the author and by a medical doctor in occupational health care was a human error. The proper acupuncture studies in Finland include a minimum of 14 to 30 ECTS of medicine, depending on the year of graduation, and lung cancer is one of the most difficult forms of cancer to diagnose even for general practitioners (Rankin et al. 2017). Mistakes can happen for any medical professional and CAM practitioner alike, but delays in treatment can lead to disease progression and missed opportunities for cure in a significant subset of patients (Rankin et al. 2017). In conventional care, it is customary to refer the patient to a specialist for diagnosis in case the general practitioner suspects cancer or another more serious disease. A similar attitude is crucial for patient safety among all CAM modalities. Wide cooperation with medical doctors would ensure patient safety and could also encourage some vulnerable patient groups to visit a doctor in time. It might also provide a bridge for communication to patients with MUPS or other patient groups who may feel more understood by CAM practitioners.

Based on these reflections, the author claims that there exists a possibility for certain groups of people to be left without early recognition of serious diseases in conventional health care and in clinics offering CAM modalities. In developed Western countries, most patients already go to a medical doctor in case they suspect anything serious. Those coming to see an acupuncturist or another CAM practitioner have often already visited a medical doctor (Eisenberg et al., 2001). Those who have considered their problems too minor for needing a doctor may still try acupuncture. In case the acupuncturists suspect any more serious health concerns, the professional acupuncturists always ask the patient to visit a doctor. In Chinese medicine education, it is necessary to teach acupuncturists to become aware of their own limitations. In acupuncture education, the students need to be taught to communicate with the patients honestly, if they cannot understand the symptoms or they have any suspicions.

The ability of an acupuncturist to recognise important clues about serious health issues depends on education and clinical experience. Even though Chinese medicine courses are not meant to produce medical doctors or to teach how to make a conventional medical diagnosis, they aim at providing enough understanding when it is necessary to refer the patient to medical care. As the popularity and acceptance of acupuncture is growing fast and more and more research about its effectiveness is emerging, the acupuncturists will receive more and more patients seeking alternatives. With growing public awareness of acupuncture, there will be more and more patients coming with grave illnesses that require conventional medical treatments. The need for basic medical education and continuous education for acupuncturists cannot therefore be stressed enough.

It is also crucial for acupuncturists, and other CAM practitioners, to network themselves with medical doctors whom they can refer the patients to or ask for an opinion. Awareness of these critical situations can also be improved with open discussion and sharing experiences with other acupuncturists or practitioners of other CAM modalities.

Some patients have withheld information from their doctors about their nutraceuticals recommended by their nutritional therapists or herbs recommended by CAM practitioners. In the study by Eisenberg et al. (2001), three fifths of CAM therapy used was not disclosed to doctors. The common reason is that the doctor didn’t ask and some patients were also afraid that the doctors would not agree or understand (Eisenberg et al., 2001). This can be very dangerous considering the potential interactions (Salminen, 2018) with drugs used in cancer treatment, for example. The possibility that the patient uses some CAM modality is ever increasing. According to Eardley et al. (2012) “the prevalence of CAM use varied widely within and across the EU countries” and could be even as high as 86% of the population in some countries. The most commonly used modality is herbal medicines. If the patients sense a strong dichotomy between CAM practitioners and medical professionals, it can cause the patients to withhold vital information. It is important that acupuncturists also recognize these dangers and are able to inform their patients and form patient relationships based on trust. They need to tell their patients to inform their doctors or practitioners of other CAM modalities about any treatments they give, especially if they prescribe any medicinal herbs or products.

The acupuncturists and Chinese medicine practitioners might also hear about the use of falsified medicines that can endanger the patients (Hamilton et al. 2016) or other unregulated and possibly harmful products. The acupuncturists can report these potentially harmful products to local authorities and inform their patients about possible dangers in their use. The author believes that information about the use of unregulated or falsified medicines might be left out during visit to a doctor just as easily as the patients withheld information, such as using CAM modalities, and an acupuncturist can instruct their patients to disclose this information.

With patients having any previous dissatisfaction with medical care, extra caution should be taken. In case of any suspicious symptoms, the patients should be instructed to see a doctor, if they have not already done so, to avoid a late diagnosis of serious medical conditions. Making patients agree to see a doctor probably requires building a good therapeutic relationship. The practitioner of any CAM modality also needs to be aware in his therapeutic relationships that a patient might also easily get a wrong idea of the effectiveness. The patient in this case reserved time to check if acupuncture could help with Ménière’s disease when medicine failed. She had already had made the assumption that vertigo was because of Ménière’s disease and that acupuncture might help. Currently, there is preliminary evidence that acupuncture might work for Ménière’s disease (He et al. 2016) but her expectations were high because of the previous success with uveitis. It is sometimes almost impossible to avoid giving false hope by just agreeing to treat any less commonly treated symptoms. Not treating or overly explaining that the treatment might not work might harm the therapeutic relationship and even prevent the referral to a doctor in case it is needed.

Reflecting upon therapeutic relationships and clinical skills after this incident, the author became more aware of possible consequences of his therapeutic practice. It would be unrealistic to think that these mistakes couldn’t ever happen in the future, but there are always ways to improve the practice. He will now reserve extra time for returning patients if a few years have passed from the last session. With this he tries to ensure that he has enough time to collect information. Even in cases of seemingly minor complaints that do not respond to acupuncture treatments, the patients will from now on be routinely encouraged to see a doctor upon termination of the course of treatment. Before, the patients have already been asked to see doctor if there have been any alarming symptoms, but minor health concerns might have been previously overlooked. The author himself sees the work of an acupuncturist very tightly interwoven with the medical profession and sees further cooperation between different medical modalities as a requirement for patient safety. The author also concludes that it is unlikely that offering acupuncture would generally cause delays in diagnosis and treatment of a serious disease like cancer, but there is definitely a lack of proper studies in this area.

References

Chiu, HY., Hsieh, YJ. and Tsai, PS. (2017) Systematic review and meta-analysis of acupuncture to reduce cancer-related pain. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2017 Mar;26(2).

Duong, N., Davis, H., Robinson, PD., Oberoi, S. Et al. (2017). Mind and body practices for fatigue reduction in patients with cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2017 Dec;120:210-216.

Eardley, Susan., Bishop, a Felicity L., Prescott, Philip. Et al. (2012) A Systematic Literature Review of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Prevalence in EU. Forsch Komplementmed 2012;19(suppl 2):18–28

Eisenberg, David M., Kessler, Ronald C., Van Rompay, Maria I. Et al. (2001). Perceptions about Complementary Therapies Relative to Conventional Therapies among Adults Who Use Both: Results from a National Survey. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2001 Sep 4;135(5):344-51.

Hamilton WL., Doyle C., Halliwell-Ewen M., Lambert G. (2016) Public health interventions to protect against falsified medicines: a systematic review of international, national and local policies. Health Policy Plan. 2016 Dec;31(10):1448-1466.

He, Jiaojun., Jiang, Liyuan., Peng, Tianqiang. et al. (2016). Acupuncture Points Stimulation for Meniere’s Disease/Syndrome: A Promising Therapeutic Approach. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2016. Article ID 6404197

Houzé B., El-Khatib H., Arbour C. (2017) Efficacy, tolerability, and safety of non-pharmacological therapies for chronic pain: An umbrella review on various CAM approaches. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2017 Oct 3;79(Pt B):192-205.

Hu, Caiqiong., Zhang, Haibo.,Wu, Wanyin. Et al. (2016) Acupuncture for Pain Management in Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Volume 2016, Article ID 1720239.

Jakes, Dan., Kirk, Ray. and Muir, Lauretta. (2014). A Qualitative Systematic Review of Patients’ Experiences of Acupuncture. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 20(9):663–671

Kim, Me-Riong., Shin Joon-Shik, Lee Jinho Lee, Lee Yoon Jae et al. (2016). Safety of Acupuncture and Pharmacopuncture in 80,523 Musculoskeletal Disorder Patients: A Retrospective Review of Internal Safety Inspection and Electronic Medical Records. Medicine. 95(18):e3635, MAY 2016.

Lipsitt, Don R., Joseph, Robert. Meyer, Donald. and Notman, Malkah T. (2015) Medically Unexplained Symptoms: Barriers to Effective Treatment When Nothing Is the Matter. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2015 Nov-Dec;23(6):438-48

MacArtney, John I. and Wahlberg, Ayo. (2014). The Problem of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Today: Eyes Half Closed?. Qualitative Health Research 2014, Vol. 24(1) 114–123.

Mcculloch M., Nachat A., Schwartz J., Casella-Gordon V. and Cook J. (2015). Acupuncture safety in patients receiving anticoagulants: a systematic review. Permanente Journal. 2015 Winter;19(1):68-73.

Ng JY., Liang L. and Gagliardi AR. (2016) The quantity and quality of complementary and alternative medicine clinical practice guidelines on herbal medicines, acupuncture and spinal manipulation: systematic review and assessment using AGREE II. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2016 Oct 29;16(1):425.

Park J., Sohn Y., White AR. and Lee H. (2014). The safety of acupuncture during pregnancy: a systematic review. Acupuncture in Medicine: Journal of the British Medical Acupuncture Society. 2014 Jun;32(3):257-66.

Potential Signals of Serious Risks/New Safety information identified from the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) Public Dashboard. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Surveillance/AdverseDrugEffects/ucm070093.htm (Last accessed 30.7.2018)

Rankin, Nicole M., York, Sarah., Stone, Emily. Et al. (2017). Pathways to Lung Cancer Diagnosis: A Qualitative Study of Patients and General Practitioners about Diagnostic and Pretreatment Intervals. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2017 May;14(5):742-753

Salminen, Kaisa. (2018) Potential metabolism-based drug interactions with isoquinoline alkaloids: an in vitro and in silico study. Publications of the University of Eastern Finland. Dissertations in Health Sciences., no 444.

Shorofi, Seyed Afshin., Arbon, Paul. (2017). Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among Australian hospital-based nurses: knowledge, attitude, personal and professional use, reasons for use, CAM referrals, and socio-demographic predictors of CAM users. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 2017 May;27:37-45.

Turner LA., Singh K., Garritty C., Tsertsvadze A. et al. (2011). An evaluation of the completeness of safety reporting in reports of complementary and alternative medicine trials. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011 Aug 22;11:67.

Warnock, Rory., Jeffries, Owen., Patterson, Stephen and Waldron, Mark. (2017) The Effects of Caffeine, Taurine, or Caffeine-Taurine Coingestion on Repeat-Sprint Cycling Performance and Physiological Responses 2017 Nov 1;12(10):1341-1347.

Witt C.M., Pach D., Brinkhaus B., Wruck K. et al. (2009). Safety of Acupuncture: Results of a Prospective Observational Study with 229,230 Patients and Introduction of a Medical Information and Consent Form. Forsch Komplementmed 2009;16:91–97.

Wu, Xinyin., Chung, Vincent CH., Hui, Edwin P. et al. (2015). Effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies for palliative care of cancer: overview of systematic reviews. Scientific Reports. 2015 Nov 26;5:16776.

Zhang, Y., Lin, L., Li, H. et al. (2018). Effects of acupuncture on cancer-related fatigue: a meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2018 Feb;26(2):415-425.

Zick, Suzanna M., Sen, Ananda., Wyatt, Gwen K. et al. (2016). Investigation of 2 Types of Self-administered Acupressure for Persistent Cancer-Related Fatigue in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncology. 2016 Nov 1;2(11):1470-1476.

Zen training in the U.S.: tradition, modernity, and trauma

Moderator’s note: Many practitioners of Asian medicine and Asian-based health modalities are grappling with questions concerning the historical roots and cultural status of their disciplines today as never before. In response, Asian Medicine Zone is launching a new series of practitioner essays exploring how changing conceptions of “tradition” and “modernity” are impacting their practice and field in the 21st century (these are organized under the tag “tradition/modernity”). If you’re interested in contributing to this series, please email a short description of your proposed essay to the moderators. Here, we’re pleased to share our first offering, which artfully explores the encounter between traditional patriarchal authority and contemporary social justice commitments in the author’s life, practice, and community.

Having spent over 30 years of my adult life as a Buddhist practitioner in the U.S., I’m certain of only one thing, which is this: in the process of spiritual maturation, the path is not always clear and straightforward. In my personal experience as a practitioner, there’s been a lot of both/and – a particular experience can be abusive and traumatic, and it can lead to insight and breakthrough. Necessary spiritual surrender can mix potently with what Western psychology calls poor boundaries. And, it seems to me, some people will always be drawn to take paths of greater risk in varying degrees, up to so-called crazy wisdom. Others will develop by staying true to conventional mores with quiet patience.

In 1984, I was living as a renunciant under a vow of complete poverty in a Buddhist community in the United States. Our teacher, a strong-willed Asian man, resided most of the time in Canada, with periodic visits to our startup temple in the Midwest. Probably like most of our convert Buddhist community, I had moved into the temple full-time with a great deal of hope and projection that the teacher, who was described by his senior students as a Zen master and enlightened being, would be my major role model of elevated qualities of compassion and wisdom as I somehow imagined them to be.

I had immediately been appointed office manager and treasurer when I moved into the temple. I started the office with a landline phone, a cardboard box for petty cash and receipts, a checkbook, and a small wooden bench that could be used as a tiny desk if one sat cross-legged on the wooden floor. There wasn’t enough money in the bank to pay our utility bills and mortgage when I moved in, so we cut every corner and pinched every penny.

It was under these pressured circumstances that I was quietly working in the office when the “Zen master” suddenly walked in and began screaming at the top of his lungs at me for making a long- distance phone call for business reasons during a time when rates were higher. As Zen students, we were taught to “eat the blame,” so I did, and simply apologized until he went away. A few days later, having complained to the temple director who told him that the reduced rate times for calling were different in the U.S. than in Canada, he sheepishly reappeared in the office and said he hadn’t had full information. This was somewhat short of an “I’m sorry I unfairly vented my rage on you.” But it was the best I could get under the circumstances.

I couldn’t talk to anyone outside our temple system about such incidents because they would immediately say, “Why don’t you leave?” And the fact was, I was also learning a great deal. There were so many beautiful aspects of our communal temple life of meditating together and manual work, cooking and cleaning and eating together. The teacher was also immensely talented and caring in many ways. It was confusing, and in the Buddhist practice we were doing, it was okay not to know everything at once.

Traditional Zen stories and Zen lore are full of anecdotes that involve hitting and yelling and enduring unfair accusations. By the time I became a renunciant, I was an adult woman with a master’s degree. I’d been married and divorced. I had worked various jobs in the secular world. And I’d been exposed to the women’s movement and lived through the civil rights era in the U.S. I was open to going through some strong, and even traumatizing experiences for the sake of spiritual training.

Things continued to be a dynamic mess. I ended up in an Asian monastery for 8 months in 1987-88. There, my life and identity as I had known them continued to be blown up. As I said some time after I returned, I felt as though I got completely chewed up by the patriarchy.

It is also completely possible that if I had been smarter and had better boundaries, I wouldn’t have ended up as badly as I did.

But I survived. I got back to California, and, struggling continuously with extreme poverty, raised a Buddhist child, and continued my practice. I promised my son and myself that I would find a way to live in Buddhist community where power was more equally distributed, and codes of ethics and democratic structures were in place. Buddhist life might continue to be a mess. But I wanted, at minimum, a more workable mess that aligned with my cultural values. I distinctly remember thinking, upon returning to the U.S. from the Asian monastic system, “I don’t have to get my way, but I will be damned if I don’t at least get to vote. I am an American, and I want my vote!”

I didn’t want to overthink any of this. All systems and forms have limitations, and attachment creates suffering – this is a universal principle of Buddhism which I personally have never found to be untrue. That being said, the reason I began Zen meditation in the first place was because I wanted to find a situation in which I could live with other people with forms of practice that encourage well-being, kindness and justice, while at the same time providing support for Awakening. And I’ve been fortunate, because I’ve spent the last eleven years working with others to create a diverse and social justice-centered urban meditation center in Oakland, California, where I live. For me, and for many others, East Bay Meditation Center has been the intersection of Dharma practice and community-based social justice activism and awareness where I can constantly explore Liberation in ways that don’t separate the spiritual world from the real experiences of structural violence that I experience or witness every day.

As a Buddhist teacher at East Bay Meditation Center, I teach in trauma-informed ways that I have learned as a yoga student from the social justice-based Niroga Institute in Oakland, California. The traditional forms of spiritual training that require students to withstand humiliation and abuse from those above them in a hierarchical model are, I’m convinced, not essential to a 21st century Eightfold Path. Why? Because for most people, especially those in communities targeted for oppression, life is already full of traumatic humiliation and abuse. What we need are ways to become resilient, whole, and wise in seeking environmentally sustainable ways to coexist nonviolently and joyfully.

My Bodhisattva vows, the same as millions of others who have taken these vows, are “to save the many beings.” Where the rubber meets the road is that we are different from one another, love is not always the answer, and conflict is inevitable. I’m fine with this particular dynamic mess of imperfection, as long as it’s worked with in the service of systemic justice and equity.

Healing Experiences of Vipassanā Practitioners in Contemporary China, Case study 5

This is a case study that is part of a series of linked posts:

Introduction, case 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5

Case 5: Candasaro

Before ordaining as a monk in Thailand, Candasaro had worked at a private factory as a production manager in Sichuan for over 30 years. In 2008 he started exploring Theravāda meditation by learning observing the breath[i] with Pa-Auk Sayadaw’s method at Jiju Mountain for about two months in Yunnan. He later gave up this practice as he could not see any sign[ii] emerged in his sitting. “My personality is quite fast-paced. It’s difficult to cultivate calmness.”[iii] In May 2011, he firstly learnt about the practice of dynamic movement at a ten-day retreat led by Luangpor Khamkhian Suvanno, from Thailand, in Hongzhou.[iv] During the retreat, he tasted a sense of joy[v], a positive outcome of meditation.

Candasaro found that dynamic movement suited him perfectly. He explained about the practice: “In the beginning [you] observe the movement of the body. Later [you can] observe the mind. All practices are similar. They firstly cultivate calmness by bringing awareness to one point. That is developing an ability of concentrating the mind. Without calmness, it is impossible to practice vipassanā. When you open the six sense doors, you hold one of them, like a monkey holding the main pillar. In dynamic movement, the main practice is moving the arms. In Mahāsi’s method, it is about the rising and falling of the abdomen. … I like observing the movement.”

He also practiced the dynamic movement at workplace. “While I was working at the control room, I managed the office work and communicated with my colleagues [when it was necessary]. The workload was not so heavy. There was only about one working our every day. It was relaxing.” Then in October 2011 Candasaro joined an organized trip to stay at WatPa Sukato[vi] for two months in South Thailand. This was the first time he travelled to Thailand. Located at Chaiyaphum Province, the temple covering an area of 185 acres, including a river and Phu Kong Mountain that was 470 meters above sea level. Sukato means ‘good’. Luang Phor Kham Khian Suwanno, the first abbot, shared his intention of building the temple, “Sukato is a place where people come and go for wellness, also for the beneficial impact of the environment, human being, river, forest and air. This is the wellness in coming, going and being. This wellness is born from earth, water, air and fire, not from one person alone. …There are shelter, food and friends who will teach, demonstrate, and give advice. Should one wish to stay here, his or her intention to practice dharma shall be fulfilled.”[vii]

In this huge forest temple, there were around 30 monks and 30 lay people only. As there were plenty established huts, every resident could stay in one hut.[viii] Every morning, all residents woke up at 3 o’clock in the early morning to prepare for the chanting and dhamma talk at 4 o’clock. Around 6 am, Candasaro and other monks, dressed in yellow monastic robe, formally visited villages nearby carrying their alms bowls for their daily alms round. (See Fig. 3 and Fig. 4) In Chinese Buddhist communities in China, alms round practices have been faded out for many centuries. With bare feet, the monks lined up tidily first and started walking towards one of the target villages. After entering the village, they stopped in front of a household where donors were waiting with cooked rice and food. Whenever people from households offered food to monks one by one, they would line up before the householders and chant blessing words in Pāli. All the monks went back to the monastery with the received alms. At around 7.30 am, volunteers in the monastery kitchen finished preparing the foods so that the monks and all residents could have their first meal. For monks, this was also the only meal according to their precepts.

In August 2012, he stayed there again for a month. In 2013, he decided to quit his job and receive early retired pension. He decided to ordain as a bhikkhu and settled at WatPa Sukato. He enjoyed his monastic life very much, “I don’t need to spend any money by living at a monastery. I have been working in government and business sectors for many years. I am very tired of them. And my wife agreed to that [the separation] …. After you practice diligently, awareness lead you to have a strong sense of renunciation from the mundane world. Firstly, [it’s] renunciation; secondly, you do not attach or crave something.” (See Fig. 5)

Although Candasaro could not speak English, he had learnt some basic Thai words to communicate with Thai people for his daily basic needs. Over the past four years, he went back to China a few times to attend retreats and also invited some friends to travel to WatPa Sukato. In 2017, he returned to China and settled in Fujian Province. He started teaching dynamic meditation and led alms round in the village.

[i] Ch. guanhuxi; P. ānāpānasati.

[ii] Ch. chanxiang; P. nimitta.

[iii] Ch. ding; P. samādhi.

[iv] Luangpor Khamkhian Suvanno was a disciple of Luangpor Teean.

[v] Ch. xi; P. piti.

[vi] See “Wa-Pa-Sukato,” Tourism Authority of Thailand, https://www.tourismthailand.org/Attraction/Wat-Pa-Sukato–3354

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Ch. gudi; P. kuṭi