This is a syndicated post that first appeared at http://recipes.hypotheses.org/9936

By Yi-Li Wu

It’s hard to set a compound fracture when the patient is in so much pain that he won’t let you touch him. For such situations, the Chinese doctor Wei Yilin (1277-1347) recommended giving the patient a dose of “numbing medicine” (ma yao). This would make him “fall into a stupor,” after which the doctor could carry out the needed surgical procedures: “using a knife to cut open [flesh], or using scissors to cut away the sharp ends of bone.” Numbing medicine was also useful when extracting arrowheads from bones, Wei said, enabling the practitioner to “use iron tongs to pull it out, or use an auger to bore open [the bone] and thus extract it.” More generally, Wei recommended using numbing medicines for all fractures and dislocation, for it would allow the doctor to manipulate the patient’s body at will.

Wei’s preferred numbing medicine was “Wild Aconite Powder” (cao wu san), and he detailed the recipe in his influential compendium, Efficacious Formulas of a Hereditary Medical Family (Shiyi dexiao fang), completed in 1337 and printed by the Imperial Medical Academy of the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368). In his preface, Wei affirmed that medical formulas were the foundation of medicine and that a doctor’s ability to cure depended on his ability to use these tools skillfully. Wei’s family had practiced medicine for five generations, and he synthesized their knowledge with that of other doctors to produce a comprehensive treatise encompassing internal medicine; the diseases of women and children; eye diseases; illnesses of the mouth, teeth, and throat; ulcers and swellings; and diseases caused by invasions of “wind” (ailments with sudden onset, including febrile epidemics and paralytic strokes). Numbing medicine appeared in Wei’s chapters on bone setting and weapon wounds.

Wei’s Wild Aconite Powder is the earliest datable recipe that I have found for surgical anesthesia in a Chinese text, and it is a valuable window onto practices that were largely transmitted orally, whether in medical families or from master to disciple. Dynastic histories relate that the legendary doctor Hua Tuo (110-207) employed a formula called mafeisan to render his patients insensible prior to cutting them, even opening up their abdomens to excise rotting flesh and noxious accumulations. Some scholars have hypothesized that mafeisan (literally “hemp-boil-powder) may have contained morphine or cannabis (ma), but its ingredients remain a mystery. A text attributed to the twelfth-century physician Dou Cai (ca. 1146) recommended using a mixture of powdered cannabis and datura flowers (shan qie zi, also called man tuo luo hua) to put patients to sleep prior to moxibustion treatments, which in this text could involve a hundred or more cones of burning mugwort placed directly on the patient’s skin. Wei Yilin’s recipe provides important additional textual evidence for a tradition of anesthetic formulas based on toxic plants, one that was clearly in circulation long before he wrote it down.

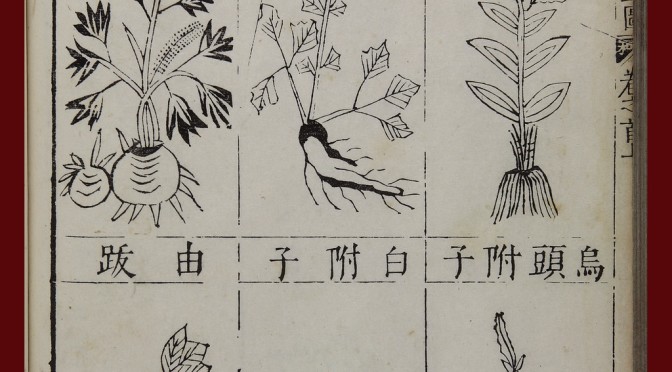

At least as far back as the Divine Farmer’s Classic of Materia Medica(3rd c.), medical authors had described aconite as highly toxic (for contemporary Roman views of aconite, see blogpost by Molly Jones-Lewis). In the right hands, however, aconite was a powerful drug, and part of the Chinese practice of using poisons to cure (see blogpost by Yan Liu). Warm and acrid, aconite could drive out pathogenic wind and cold from the body, break up stagnant accumulations, and invigorate the body’s vitalities. In the language of Chinese yin-yang cosmology, it nourished yang—all that was active, heating, external, and ascending. The main aconite root was considered more toxic than the subsidiary roots (designated by the separate name fu zi, “appended offspring”), and the wild form was more potent than the cultivated variety.

Wei’s numbing recipe consisted of 13 plant ingredients, including the main roots of both wild and cultivated (Sichuanese) aconite, along with drugs known as good for treating wounds:

Young fruit of the honey locust (zhu yao zao jiao)

Momordica seeds (mu bie zi)

Tripterygium (zi jin pi)

Dahurian angelica (bai zhi)

Pinellia (ban xia)

Lindera (wu yao)

Sichuanese lovage (chuan xiong)

Aralia (tu dang gui)

Sichuanese aconite (chuan wu)

Five taels each[1]Star anise (bo shang hui xiang)

“Sit-grasp” plant (zuo ru), simmered in wine until hot

Wild aconite (cao wu)

Two taels eachCostus (mu xiang), three mace

Combine the above ingredients. Without pre-roasting, make into a powder. In all cases of crushed or broken or dislocated bones, use two mace, mixed into high quality red liquor.

Wei most likely learned this formula from his great-uncle Zimei, a specialist in bonesetting and wounds. Its local origins are also suggested by its use of zuo ru, literally “sit-grasp”, a toxic plant whose botanical identity is unclear. However, according to the eighteenth-century Gazetteer of Jiangxi (Jiangxi tong zhi), sit-grasp was native to Jiangxi, Wei’s home province, and was used by indigenes to treat injuries from blows and falls. While classical pharmacology focused on the curative effects of aconite, Wei’s anesthetic relied on aconite’s ability to stupefy and numb, while curbing its ability to kill. If an initial dose failed to make the patient go under, Wei said, the doctor could carefully administer additional doses of wild aconite, sit-grasp herb and the datura flower.

In subsequent centuries, as medical texts proliferated, we find additional examples of numbing medicines that employed aconite, datura, and other toxic plants, employed when setting bones and draining abscesses, and to numb injured flesh before repairing tears and lacerations to ears, noses, lips, and scrotums. Such manual and surgical therapies are an integral part of the history of healing in China.

Yi-Li Wu is a Center Associate of the Lieberthal-Rogel Center for Chinese Studies at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (US) and an affiliated researcher of EASTmedicine, University of Westminster, London (UK). She earned a Ph.D. in history from Yale University and was previously a history professor at Albion College (USA) for 13 years. Her publications include Reproducing Women: Medicine, Metaphor, and Childbirth in Late Imperial China (University of California Press, 2010) and articles on medical illustration, forensic medicine, and Chinese views of Western anatomical science. She is currently completing a book on the history of wound medicine in China.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Wellcome Trust Medical Humanities Award “Beyond Tradition: Ways of Knowing and Styles of Practice in East Asian Medicines, 1000 to the present” (097918/Z/11/Z). I am also grateful to Lorraine Wilcox for directing me to the work of Dou Cai.

*****

[1] The weight of the tael (Ch. liang) has varied over time, but during Wei’s lifetime would have been equivalent to 40 grams. A mace (Ch. qian) is one-tenth of a tael.